History - Mauryan Empire: State and Society | 9th Social Science : History : Intellectual Awakening and Socio-Political Changes

Chapter: 9th Social Science : History : Intellectual Awakening and Socio-Political Changes

Mauryan Empire: State and Society

Mauryan Empire: State and Society

Mauryan Kings

Vishnugupta, who was later known as Chanakya or

Kautilya, fell out with the Nanda king and vowed to dethrone him. Chandragupta

perhaps inspired by Alexander of Macedonia, was raising an army and looking for

opportunities to establish a kingdom of his own. On hearing the news of

Alexander’s death, Chandragupta stirred up the people and with their help drove

away the Greek garrison that Alexander had left at Taxila. Then he and his

allies marched to Pataliputra and defeated the Nanda king in 321 BCE. Thus

began the reign of the Mauryan dynasty.

During Chandragupta’s reign, Seleucus, the general

of Alexander, who had control over countries from Asia Minor to India, crossed

the Indus only to be defeated by Chandragupta. Seleucus’s envoy, Megasthenes,

is said to have remained in India and his account titled Indica is a useful record about Mauryan polity and society.

After gaining control over the Gangetic plain,

Chandragupta turned his attention to north-west to take advantage of the void

created by Alexander’s demise. These areas comprising the present-day

Afghanistan, Baluchistan and Makran surrendered without any resistance.

Thereupon Chandragupta moved to Central India. According to Jaina tradition,

towards the end of his life, Chandragupta, who had by now become an ardent

follower of Jainism, abdicated his throne in favour of his son Bindusara.

Bindusara, during his rule, succeeded in extending

the Mauryan empire upto Karnataka. At the time of his death, a large part of

the subcontinent had come under Mauryan

suzerainty.

Ashoka succeeded Bindusara in 268 BCE. Desirous of

bringing the remaining parts of South India into his empire, Ashoka waged a war

against Kalinga in the eighth year of his reign. The people of Kalinga fought

bravely, but they were defeated after a large-scale slaughter. This war and

slaughter affected Ashoka so much that he decided to give up war. Ashoka became

an ardent Buddhist after meeting the Buddhist monk Upagupta and propounded his

Dharma. The only true conquest, he proclaimed, is the conquest of self and the

conquest of men’s hearts by the dhamma

(Pali) or dharma (Sanskrit). He

issued edicts, which were carved out in the rock.

In one of his Kalinga edicts, he tells us his

horror and sorrow over the deaths which the war and conquest caused. In yet

another edict, he makes it known that Ashoka would not tolerate any longer the

death or captivity of even hundredth or thousandth part of the number killed

and made captive in Kalinga.

Ashoka’s passion for protecting life extended to

animals as well Hospitals were constructed for them and animal sacrifice was

forbidden. Ashoka sent his son Mahendra and his daughter Sanghamitra to Ceylon

to spread his message of Dharma there. Ashoka died after ruling for 38 years.

Mauryan Administration

The Mauryan state in its early years undertook some

measures that were positive for the development of society. The state raised

taxes to finance a huge standing army and a vast bureaucracy.

The Mauryans had evolved a very efficient system of

governance. The king, as the head of the administration, was assisted by a

council of ministers. There were mahamatriyas,

who functioned as secretaries to the ministers. The person in charge of revenue

and expenditure was samaharta. The

empire was divided into four provinces and these provinces were administered by

governors, who were usually princes or from the royal family.

The district was under a sthanika, while gopas

were in charge of five to ten villages. The urban administration was under a nagaraka. Six committees with five

members each carried on their duties under him. They were to take care of the

foreigners, to register the birth and death of the citizens, to look after

trade and commerce, to supervise different manufactures and to collect excise

duties and custom duties respectively. Like the city or town administration,

the military department was also managed by a board of 30 members, split into

six committees, with five members in each of them. At the village level, there

was gramani, whose responsibility was

maintaining the boundaries, keeping the records of land and a census of

population and livestock. In order to keep a vigil over the entire

administration, including the conduct of officers, a well-knit spy system was

evolved and put in place. Justice was administered through well-established

courts in all major towns and cities. Punishment for crimes was severe.

The state used the surplus appropriated for the

development of the rural economy by founding new settlements, granting land and

encouraging the people to settle as farmers. It also organised irrigation

projects and controlled the distribution of water. There was state control of

agriculture, mining, industry and trade. The state discouraged the emergence of

private property in land and banned its sale. The Mauryan state gave further

boost to urban development. It secured land trade routes to Iran and

Mesopotamia, as well as to the kingdoms of northern China. Arthasastra refers to Kasi (Benares), Vanga (Bengal), Kamarupa (Assam) and Madurai as textile centres. The

distribution of black polished ware of northern India as far as South India is

indicative of the extent of trade during the Mauryan rule. Trade contributed to

urbanisation in a big way. New cities such as Kaushambi, Bhita, Vaishali and

Rajagriha had sprung up in the doab

region.

Educational Centres

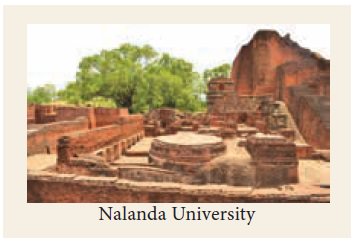

Monasteries and temples served the purpose of

imparting education. Nalanda was a great monastery built by the Magadha Empire.

Educational centres offered Buddhist and Vedic literature, logic, grammar,

medicine, philosophy and astronomy. Even the science of war was taught. Nalanda

became the most renowned seat of learning in course of time. It was supported

by the revenues of 100 villages. No fees were charged to the students and they

were provided free board and lodging.

Related Topics