Chapter: Medical Physiology: The Microcirculation and the Lymphatic System: Capillary Fluid Exchange, Interstitial Fluid, and Lymph Flow

Rate of Lymph Flow

Rate of Lymph Flow

About 100 milliliters per hour of lymph flows through the thoracic duct of a resting human, and approxi-mately another 20 milliliters flows into the circulation each hour through other channels, making a total estimated lymph flow of about 120 ml/hr or 2 to 3 liters per day.

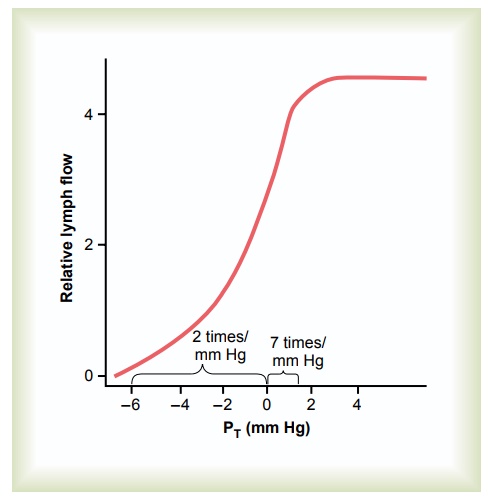

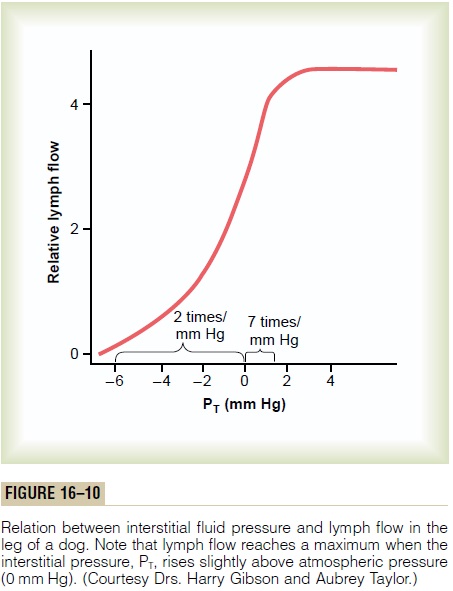

Effect of Interstitial Fluid Pressure on Lymph Flow. Figure16–10 shows the effect of different levels of interstitial fluid pressure on lymph flow as measured in dog legs.

Note that normal lymph flow is very little at intersti-tial fluid pressures more negative than the normal value of -6 mm Hg. Then, as the pressure rises to 0 mm Hg (atmospheric pressure), flow increases more than 20-fold. Therefore, any factor that increases interstitial fluid pressure also increases lymph flow if the lymph vessels are functioning normally. Such factors include the following:

· Elevated capillary pressure

· Decreased plasma colloid osmotic pressure

· Increased interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure

· Increased permeability of the capillaries

All of these cause a balance of fluid exchange at the blood capillary membrane to favor fluid movement into the interstitium, thus increasing interstitial fluid volume, interstitial fluid pressure, and lymph flow all at the same time.

However, note in Figure 16–10 that when the inter-stitial fluid pressure becomes 1 or 2 millimeters greater than atmospheric pressure (greater than 0 mm Hg), lymph flow fails to rise any further at still higher pres-sures. This results from the fact that the increasing tissue pressure not only increases entry of fluid into the lymphatic capillaries but also compresses the outside surfaces of the larger lymphatics, thus imped-ing lymph flow. At the higher pressures, these two factors balance each other almost exactly, so that lymph flow reaches what is called the “maximum lymph flow rate.” This is illustrated by the upper level plateau in Figure 16–10.

Lymphatic Pump Increases Lymph Flow. Valves exist in alllymph channels; typical valves are shown in Figure

Motion pictures of exposed lymph vessels, both in animals and in human beings, show that when a collecting lymphatic or larger lymph vessel becomes stretched with fluid, the smooth muscle in the wall of the vessel automatically contracts. Furthermore, each segment of the lymph vessel between successive valves functions as a separate automatic pump. That is, even slight filling of a segment causes it to contract, and the fluid is pumped through the next valve into the next lymphatic segment. This fills the subsequent segment, and a few seconds later it, too, contracts, the process continuing all along the lymph vessel until the fluid is finally emptied into the blood circulation. In a very large lymph vessel such as the thoracic duct, this lym-phatic pump can generate pressures as great as 50 to 100 mm Hg.

Pumping Caused by External Intermittent Compression of the Lymphatics. In addition to the pumping causedby intrinsic intermittent contraction of the lymph vessel walls, any external factor that intermittently compresses the lymph vessel also can cause pumping. In order of their importance, such factors are:

· Contraction of surrounding skeletal muscles

· Movement of the parts of the body

· Pulsations of arteries adjacent to the lymphatics

· Compression of the tissues by objects outside the body

The lymphatic pump becomes very active during exer-cise, often increasing lymph flow 10- to 30-fold. Con-versely, during periods of rest, lymph flow is sluggish, almost zero.

Lymphatic Capillary Pump. The terminal lymphatic capil-lary is also capable of pumping lymph, in addition to the lymph pumping by the larger lymph vessels. The walls of the lymphatic capillaries are tightly adherent to the sur-rounding tissue cells by means of their anchoring filaments. Therefore, each time excess fluid enters the tissue and causes the tissue to swell, the anchoring filaments pull on the wall of the lymphatic capillary, and fluid flows into the terminal lymphatic capillary through the junctions between the endothelial cells. Then, when the tissue is compressed, the pressure inside the capillary increases and causes the overlap-ping edges of the endothelial cells to close like valves. Therefore, the pressure pushes the lymph forward into the collecting lymphatic instead of backward through the cell junctions.

The lymphatic capillary endothelial cells also contain a few contractile actomyosin filaments. In some animal tissues (e.g., the bat’s wing) these fila-ments have been observed to cause rhythmical con-traction of the lymphatic capillaries in the same way that many of the small blood and larger lymphatic vessels also contract rhythmically. Therefore, it is probable that at least part of lymph pumping results from lymph capillary endothelial cell contraction in addition to contraction of the larger muscular lymphatics.

Summary of Factors That Determine Lymph Flow. From theabove discussion, one can see that the two primary factors that determine lymph flow are (1) the intersti-tial fluid pressure and (2) the activity of the lymphatic pump. Therefore, one can state that, roughly, the rateof lymph flow is determined by the product of intersti-tial fluid pressure times the activity of the lymphatic pump.

Related Topics