Chapter: Medical Physiology: The Microcirculation and the Lymphatic System: Capillary Fluid Exchange, Interstitial Fluid, and Lymph Flow

Interstitial Fluid Hydrostatic Pressure

Interstitial Fluid Hydrostatic Pressure

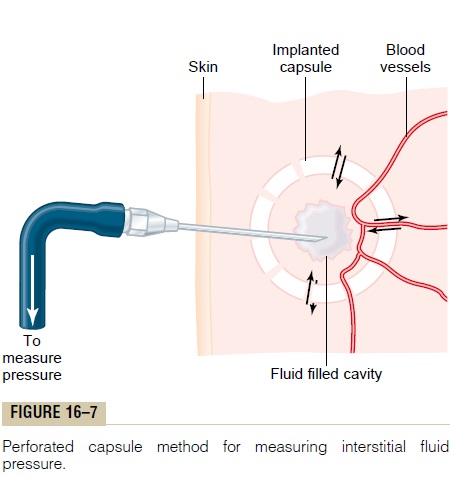

As is true for the measurement of capillary pressure, there are several methods for measuring interstitial fluid pressure, and each of these gives slightly differ-ent values but usually values that are a few millime-ters of mercury less than atmospheric pressure, that is, values called negative interstitial fluid pressure. The methods most widely used have been (1) direct can-nulation of the tissues with a micropipette, (2) meas-urement of the pressure from implanted perforated capsules, and (3) measurement of the pressure from a cotton wick inserted into the tissue.

Measurement of Interstitial Fluid Pressure Using the Micropipette. The same type of micropipette used formeasuring capillary pressure can also be used in some tissues for measuring interstitial fluid pressure. The tip of the micropipette is about 1 micrometer in diameter, but even this is 20 or more times larger than the sizes of the spaces between the proteoglycan filaments of the interstitium. Therefore, the pressure that is measured is probably the pressure in a free fluid pocket.

The first pressures measured using the micropipette method ranged from -1 to +2 mm Hg but were usually slightly positive. With experience and improved equip-ment for making such measurements, more recent pres-sures have averaged about -2 mm Hg, giving average pressure values in loose tissues, such as skin, that are slightly less than atmospheric pressure.

Measurement of Interstitial Free Fluid Pressure in Implanted Per- forated Hollow Capsules. Interstitial freefluid pressuremeasured by this method when using 2-centimeter diameter capsules in normal loose subcutaneous tissue averages about -6 mm Hg, but with smaller capsules, the values are not greatly different from the -2 mm Hg measured by the micropipette in Figure 16-7.

Measurement of Interstitial Free Fluid Pressure by Means of a Cotton Wick. Still another method is to insert into atissue a small Teflon tube with about eight cotton fibers protruding from its end. The cotton fibers form a “wick” that makes excellent contact with the tissue fluids and transmits interstitial fluid pressure into the Teflon tube: the pressure can then be measured from the tube by usual manometric means. Pressures measured by this technique in loose subcutaneous tissue also have been negative, usually measuring -1 to -3 mm Hg.

Interstitial Fluid Pressures in Tightly Encased Tissues

Some tissues of the body are surrounded by tight encasements, such as the cranial vault around the brain, the strong fibrous capsule around the kidney, the fibrous sheaths around the muscles, and the sclera around the eye. In most of these, regardless of the method used for measurement, the interstitial fluid pressures are usually positive. However, these intersti-tial fluid pressures almost invariably are still less than the pressures exerted on the outsides of the tissues by their encasements. For instance, the cerebrospinal fluid pressure surrounding the brain of an animal lying on its side averages about +10 mm Hg, whereas the braininterstitial fluid pressureaverages about+4 to+6 mmHg. In the kidneys, the capsular pressure surrounding the kidney averages about +13 mm Hg, whereas the reported renal interstitial fluid pressures have averaged about +6 mm Hg. Thus, if one remembers that the pressure exerted on the skin is atmospheric pressure, which is considered to be zero pressure, one might for-mulate a general rule that the normal interstitial fluid pressure is usually several millimeters of mercury neg-ative with respect to the pressure that surrounds each tissue.

Is the True Interstitial Fluid Pressure in Loose Subcutaneous Tissue Subatmospheric?

The concept that the interstitial fluid pressure is sub-atmospheric in many if not most tissues of the body began with clinical observations that could not be explained by the previously held concept that intersti-tial fluid pressure was always positive. Some of the per-tinent observations are the following:

1. When a skin graft is placed on a concave surface of the body, such as in an eye socket after removal of the eye, before the skin becomes attached to the sublying socket, fluid tends to collect underneath the graft. Also, the skin attempts to shorten, with the result that it tends to pull it away from the concavity. Nevertheless, some negative force underneath the skin causes absorption of the fluid and usually literally pulls the skin back into the concavity.

2.Less than 1 mm Hg of positive pressure is required to inject tremendous volumes of fluid into loose subcutaneous tissues, such as beneath the lower eyelid, in the axillary space, and in the scrotum. Amounts of fluid calculated to be more than 100 times the amount of fluid normally in the interstitial space, when injected into these areas, cause no more than about 2 mm Hg of positive pressure. The importance of these observations is that they show that such tissues do not have strong fibers that can prevent the accumulation of fluid. Therefore, some other mechanism, such as a negative fluid pressure system, must be available to prevent such fluid accumulation.

3.In most natural cavities of the body where there is free fluid in dynamic equilibrium with the surrounding interstitial fluids, the pressures that have been measured have been negative. Some of these are the following:

Intrapleural space: -8 mm Hg

Joint synovial spaces: -4 to -6 mm Hg

Epidural space: -4 to -6 mm Hg

4.The implanted capsule for measuring the interstitial fluid pressure can be used to record dynamic changes in this pressure. The changes are approximately those that one would calculate to occur (1) when the arterial pressure is increased or decreased, (2) when fluid is injected into the surrounding tissue space, or (3) when a highly concentrated colloid osmotic agent is injected into the blood to absorb fluid from the tissue spaces. It is not likely that these dynamic changes could be recorded this accurately unless the capsule pressure closely approximated the true interstitial pressure.

Summary—An Average Value for Negative Interstitial Fluid Pressure in Loose Subcutaneous Tissue. Although theaforementioned different methods give slightly differ-ent values for interstitial fluid pressure, there currently is a general belief among most physiologists that the true interstitial fluid pressure in loose subcutaneous tissue is slightly less subatmospheric, averaging about -3 mm Hg.

Pumping by the Lymphatic System Is the Basic Cause of the Negative Interstitial Fluid Pressure

The lymphatic system is discussed, but we need to understand here the basic role that this system plays in determining interstitial fluid pressure. The lymphatic system is a “scavenger” system that removes excess fluid, excess protein molecules, debris, and other matter from the tissue spaces. Normally, when fluid enters the terminal lymphatic capillaries, the lymph vessel walls automatically contract for a few seconds and pump the fluid into the blood circulation. This overall process creates the slight negative pres-sure that has been measured for fluid in the interstitial spaces.

Related Topics