Chapter: Psychology: Perception

Motion Perception: What Is It Doing?

MOTION PERCEPTION : WHAT IS IT DOING ?

We obviously want to know what

objects are in view and where they’re located, but we also want to know what

these objects are doing. Are they moving or standing still, approaching slowly

or rapidly, racing toward the food we wanted for ourselves, or head-ing off in

some altogether different direction? These questions bring us to a different

aspect of perception—namely, how we perceive motion.

Retinal Motion

One might think that the

perception of motion is extremely simple: If an object in our world moves, then

the image cast by that object moves across our retinas. We detect that image

motion, and thus we perceive movement.

As we’ll soon see, however, this

account is way too simplistic. Still, it contains a key element of truth: We do

detect an image’s motion on the retina, and this is one aspect of the overall

process of motion perception. More specifically, some cells in the visual

cortex respond to image movements on the retina by firing at an increased rate

when-ever movement is present. However, these cells don’t respond to just any

kind of move-ment, because the cells are direction

specific. Thus, the cells fire if a stimulus moves across their receptive

field from, say, left to right; but not if the stimulus moves from right to

left. (Other cells, of course, show the reverse pattern.) These cells are

therefore well suited to act as motion

detectors (see, for example, Vaultin & Berkeley, 1977).

Apparent Movement

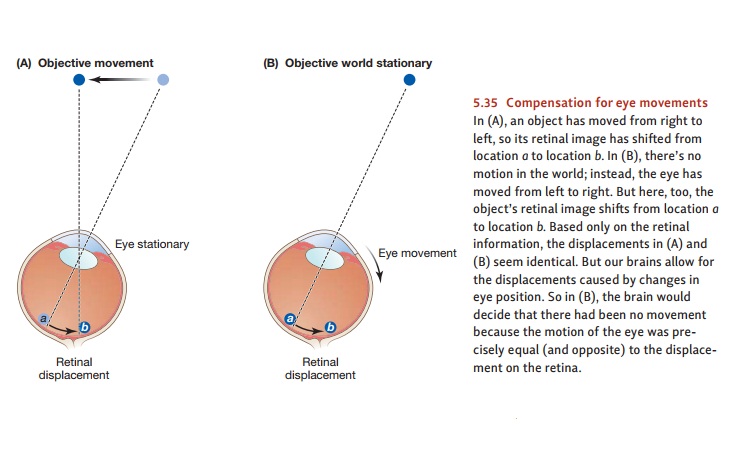

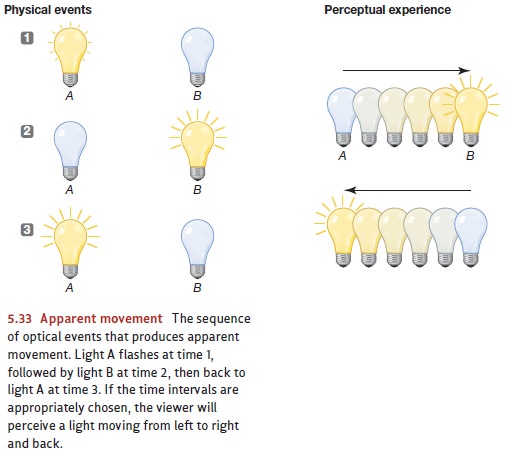

It’s clear, however, that retinal

motion is only part of the story. Suppose we turn on a light in one location in

the visual field, then quickly turn it off, and after an appropri-ate interval

(somewhere between 30 and 200 milliseconds) turn on a second light in a

different location. The result is apparent

movement. The light appears to travel from one point to another, even

though there was no motion and, indeed, no stimulation whatsoever in the

locations between the two lights (Figure 5.33). This phenomenon is perceptually

quite compelling; given the right timing, apparent movement is

indistin-guishable from real movement (Wertheimer, 1912). This is why the

images in movies seem to move, even though movies actually consist of a

sequence of appropriately timed still pictures (Figure 5.34).

Apparent movement might seem like an artificial phenomenon because the objects in our world tend to move continuously —they don’t blink out of existence here and then reappear a moment later there. It turns out, however, that, the motion we encounter in the world is often so fast that it’s essentially just a blur across the retina, and so triggers no response from the retinal motion detectors. Even so, we do perceive the motion by perceiv-ing the object first to be in one place and then, soon after, to be somewhere else. In this way, the phenomenon of apparent movement actually mirrors a process that we rely on all the time, thanks to the fact that our eyes often need to work with brief “samples” taken from the stream of continuous motion (Adelson & Bergen, 1985).

Eye Movements

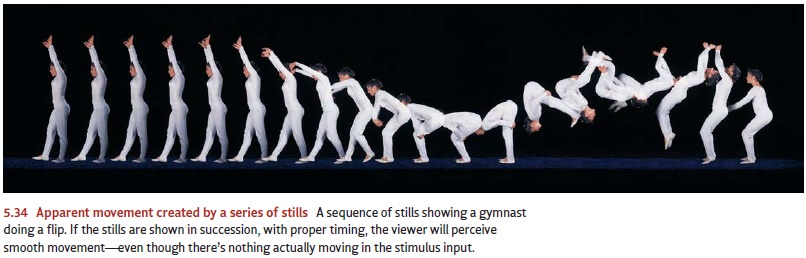

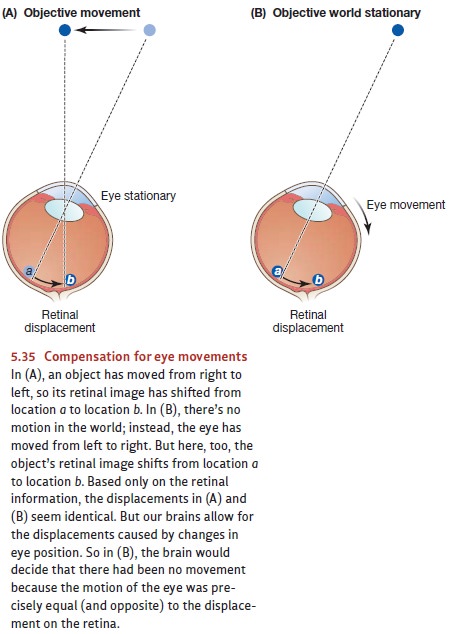

As you look around the world,

you’re constantly moving your head and eyes. This activ-ity creates another

complication for motion perception. Each movement brings you a somewhat

different view, and so each movement necessarily causes a change in the retinal

image. But, despite all this retinal motion, the world doesn’t seem to move

each time you shift your viewing position. Clearly, it takes more than motion

across the retina to produce a perception of motion in the world.

But how do you avoid becoming

confused about this retinal motion? How do you manage to separate the retinal

motion that’s caused by movement in the world from the retinal motion produced

by a change in your viewing position? The answer paral-lels our earlier

discussion of constancy. As we’ve seen, people take viewing distance into account when judging size, and that’s how they achieve size constancy. In the same way,

you seem to take your own movements

into account when judging the position

of objects in the world, and so you perceive the objects as having position constancy. How does this work?

Whenever you move your eyes or turn your head, you unconsciously compute the

shift in the retinal image that your own motion will produce, and you cancel

out this amount of movement in interpreting the visual input (Figure 5.35). The

result is constancy.

Here’s a specific example.

Imagine you’re about to move your eyes 5 degrees to the left. Even before

making the movement, you know that it will cause the retinal image to shift 5

degrees to the right. You can therefore compare this anticipated shift with the

shift that actually occurs; if they match, then you know that you produced all

of the reti-nal motion—and so there was no movement in the environment. In

algebraic terms, we can think of this canceling-out process this way: When you

move your eyes, there will be a 5-degree shift; but 5 degrees right of

anticipated change minus 5 degrees right of actual change yields zero change

overall. The zero change, of course, is what you per-ceive in this situation

—no motion (Bridgeman & Stark, 1991).

Evidence for this claim comes

from studies in which some heroic experimenters had themselves injected with

drugs that temporarily paralyzed their eye muscles. They reported that under

these circumstances, the world appeared to jump around whenever they tried to

move their eyes—just what canceling-out theory would predict. The brain ordered

the eyes to move, say, 10 degrees to the right; and so it anticipated that the

reti-nal image would shift 10 degrees to the left. But the paralyzed eyes couldn’t

follow the command, so no retinal shift took place. In this setting, the normal

cancellation process failed; as a result, the world appeared to jump with each

eye movement. (Algebraically, this is 10 degrees left of anticipated change

minus zero degrees of actual change, yield-ing 10 degrees left overall. The

visual system interpreted this 10-degree overall difference as a motion

signal.) These studies strongly confirm the canceling-out theory (Matin,

Picoult, Stevens, Edwards, & MacArthur, 1982).

Induced Motion

Clearly, then, motion perception

depends on several factors. Movement of an image across the retina stimulates

motion detectors in the visual cortex (and elsewhere in the brain), and this

certainly contributes to movement perception. However, activity in these

detectors isn’t necessary for us to perceive motion; in apparent movement, the

detectors are silent but we perceive motion anyhow. Activity in the detectors

is also, by itself, not sufficient

for us to perceive motion: If those detectors register some move-ment, but the

nervous system calculates that the movement was caused by a change in the

observer’s position, then no motion is perceived.

Even with all of this said,

there’s a further step in the process of motion perception, because we not only

detect motion but also interpret it.

This interpretation can be demonstrated in many ways, including the phenomenon

of induced motion. Consider a ball

rolling on a billiard table. We see the ball as moving and the table at rest.

But why not the other way around? We can definitely see the ball getting closer

and closer to the table’s edge; but, at the same time, we can see the table’s

edge getting closer and closer to the ball. Why, then, do we perceive the

movement as “belonging” entirely to the ball, while the table seems to be

sitting still?

Evidence suggests that our

perception in this case is the result of a bias in our inter-pretation: We tend

to perceive larger objects as still and smaller objects as moving. In addition,

if one object encloses another, the first tends to act as a stationary frame so

that we perceive the enclosed object as moving. These biases lead to a correct

perception of the world in most cases, but they can also cause errors. In one

study, research partic-ipants were shown a luminous rectangular frame in an

otherwise dark room. Inside the frame was a luminous dot. As the subjects

watched, the rectangle moved upward while the dot stayed in place. But the

subjects perceived something else. They described the dot as moving downward,

in the direction opposite to the frame’s motion. Participants had correctly

perceived that the dot was moving closer to the rectangle’s bottom edge and

farther from its top edge. But they misperceived the source of this change.

The physical movement of the

frame had induced the perceived movement of the enclosed shape.

Similar effects can easily be

observed outside of the laboratory. The moon seems to sail through the clouds;

the base of a bridge seems to float upstream, against the river’s current. In

both cases, we see the surrounded object as moving and the frame as stay-ing

still—exactly as in the laboratory findings. A related (and sometimes

unsettling) phenomenon is induced motion

of the self. If you stand on the bridge that you perceive as moving, you

feel as if you’re moving along with it. The same effect can occur when you’re

sitting in a car in traffic: You’ve stopped at a red light and then, without

warning, the car alongside you starts moving forward. You can sometimes get the

feeling that for just a moment, you (and your car) are moving backward—even

though you’re sitting per-fectly still.

The Correspondence Problem

Induced motion provides one

illustration of how our perception of motion depends on interpretation. Another

illustration, and a different type of interpretation, is involved in the

so-called correspondence problem—the

problem of deciding, as you move from one view to the next, which elements in

the second view correspond with which elements in the first view (e.g., Weiss,

Simoncelli, & Adelson, 2002; Wolfe, Kluender, & Levi, 2006). To see how

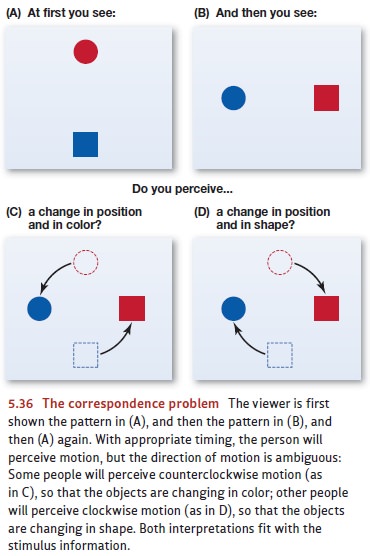

this problem can arise, consider the stimulus pattern shown in Figure 5.36. At

one moment, you’re shown the pattern in panel A; then, a moment later, the

pattern in B; then the pattern in A again; and so on back and forth. What will

you perceive? With some adjustment of the timing, we can set things up so that

this display will produce apparent movement, but what will the movement be?

Will you perceive a red dot moving counterclockwise and turning blue, as shown

in panel C? Or will you perceive a dot moving clockwise, and chang-ing into a

square, as shown in panel D?

For the display shown in Figure

5.36, there’s no “correct” solution to the correspon-dence problem. The

solutions leading to panel C and panel D both make sense. Thus, the stimuli

shown in panels A and B are truly ambiguous; so it’s no surprise that some

people will perceive the motion illustrated in C and some will perceive the

pattern in D. Indeed, an individual can perceive one of these patterns for a

while and then abruptly shift her perception and perceive the other.

As we noted in our discussion of

apparent movement, many real-world circum-stances involve motion that’s fast

enough to be just a “blur” for the visual cortex’s motion detectors. The only

way we can detect this motion is to note that the stimuli were first here, and then there, and to infer from this that the stimuli had moved. It’s

exactly this situation that creates the correspondence problem—and so we often

encounter this problem in our everyday perception of the world. As in many

aspects of perception, our decision about the correspondence (i.e., what goes

with what) is made quickly and easily; and so we don’t realize that we have, in

fact, interpreted the input. But the role of our interpretation becomes clear

whenever our perception is mistaken. This

is, for example, why we perceive spirals that are merely spinning as“growing

outward” toward us, why we observe rotating barber poles to be moving upward,

and why a fast-spinning wagon wheel that’s turning clockwise can end up looking

like it’s actually spinning counterclockwise. In each case, the misperception

grows out of an incorrect solution to the correspondence problem, and hence a

con-fusion about which elements in the current view correspond with which

elements in the scene just a moment ago.

The correspondence problem is an

important aspect of motion perception. As we said at the outset, our perception

of the world usually seems immediate and effortless. We open our eyes and we

see, with no apparent need to interpret or calculate. Even so, our per-ception

of the world does involve a lot of steps and quite a few inferences. We become

aware of those steps and inferences when they lead us astray, such as when they

lead to an illusion of one sort or another. But it’s important to recognize

that the illusions arise only because interpretation is always a part of our

perceptual process. Otherwise, if the interpretation weren’t in place, then

there’d be no way for the interpretation to go wrong! Perception, in other

words, is always an active process—even if we normally don’t detect that

activity.

Related Topics