Chapter: Psychology: Perception

Form Perception: What Is It?: The Importance of Features

FORM PERCEPTION :WHAT IS IT

The ability to recognize objects

is, of course, enormously important for us. If we couldn’t tell a piece of

bread from a piece of paper, we might try to write on the bread and eat the

paper. If we couldn’t tell the difference between a lamppost and a potential

mate, our social lives would be strange indeed. So how do we manage to

recognize bread, paper, mates, and myriad other objects? In vision, our primary

means of recog-nizing objects is through the perception of their form. Of

course, we sometimes do rely on color (e.g., a violet) and occasionally on size

(e.g., a toy model of an automobile); but in most cases, form is our major

avenue for identifying what we see. The question is how? How do we recognize the forms and patterns we see in the world

around us?

The Importance of Features

One simple hypothesis regarding

our ability to recognize objects is suggested by data. There we saw that the

visual system contains cells that serve as feature

detectors—and so one of these cells might fire if a particular angle is in

view;another might fire if a vertical line is in view; and so on. Perhaps,

therefore, we just need to keep track of which feature detectors are firing in

response to a particular input; that way, we’d have an inventory of the input’s

features, and we could then compare this inventory to some sort of checklist in

memory. Does the inventory tell us that the object in front of our eyes has

four right angles and four straight sides of equal length? If so,then it must

be a square. Does the inventory tell us that the object in view has four legs

and a very long neck? If so, we conclude that we’re looking at a giraffe.

Features do play a central role

in object recognition. If you detect four straight lines on an otherwise blank

field, you’re not likely to decide you’re looking at a circle or a picture of

downtown Chicago; those perceptions don’t fit with the set of features

pre-sented to you by the stimulus. But let’s be clear from the start that there

are some com-plexities here. For starters, consider the enormous variety of

objects we encounter, perceive, and recognize: cats and cars, gardens and

gorillas, shoes and shops; the list goes on and on. Do we have a checklist for

each of these objects? If so, how do we search through this huge set of checklists,

so that we can recognize objects the moment they appear in front of us?

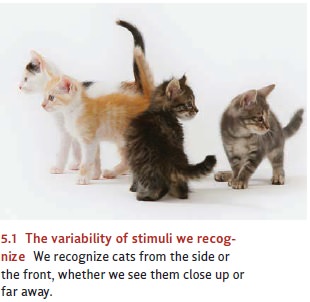

Besides that, for any one of the

objects we can recognize there is still more variety. After all, we recognize

cats when we see them close up or far away, from the front or the side, and

sitting down or walking toward us (Figure 5.1). Do we have a different feature

checklist for each of these views? Or do we somehow have a procedure for

converting these views into some sort of “standardized view,” which we then

compare to a check-list? If so, what might that standardization procedure be?

We clearly need some more theory to address these issues. (For more on how we

might recognize objects despite changes in our view of them, see Tarr, 1995;

Vuong & Tarr, 2004.)

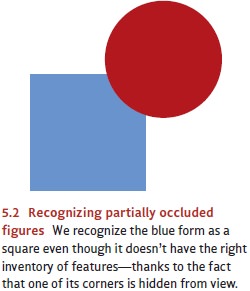

Similarly, we often have partial views of the objects around us;

but we can recognize them anyway. Thus, we recognize a cat even if it’s sitting

behind a tree and we can see only its head and one paw. We recognize a chair

even when someone is sitting on it, blocking much of the chair from view. We

identify the blue form in Figure 5.2 as a square, even though one corner is

hidden. These facts, too, must be accommodated by our theory of recognition.

Related Topics