Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Musculoskeletal Care Modalities

Joint Replacement - Managing the Patient Undergoing Orthopedic Surgery

JOINT REPLACEMENT

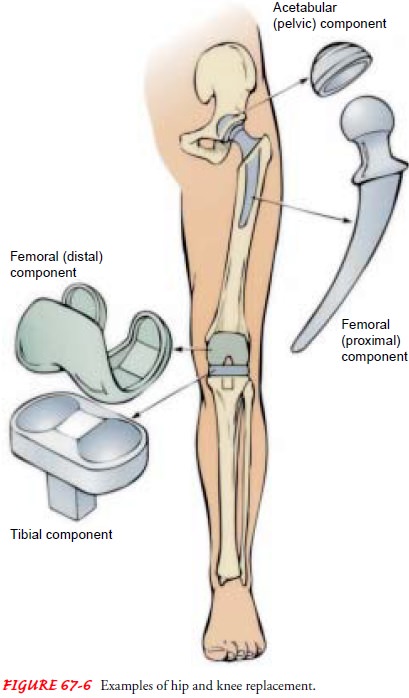

Patients with severe joint pain and disability may undergo joint replacement. Conditions contributing to joint degeneration in-clude osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease), rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, and congenital deformity. Some fractures (eg, femoral neck fracture) may cause disruption of the blood supply and subsequent avascular necrosis; management with joint re-placement may be elected over ORIF. Joints frequently replaced include the hip, knee (Fig. 67-6), and finger joints. Less frequently, more complex joints (shoulder, elbow, wrist, ankle) are replaced. The procedure is usually an elective one.

Most joint replacements

consist of metal and high-density polyethylene components. Finger prostheses

are usually Silastic. The joint implants may be cemented in the prepared bone

with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), a bone-bonding agent that has properties

similar to bone. Loosening of the prosthesis due to cement–bone interface

failure is a common reason for prosthesis failure. Press-fit, ingrowth

prostheses (porous-coated, cementless artificial joint components) that allow

the patient’s bone to grow into and securely fix the prosthesis in the bone are

alternatives to cemented prostheses. Accurate fitting and the presence of

healthy bone with adequate blood supply are important in the use of ce-mentless

components. Much progress has been made in reducing prosthesis failure rate

through improved techniques, improved materials, and use of bone grafts.

With joint replacement,

excellent pain relief is obtained in most patients. Return of motion and

function depends on pre-operative soft tissue condition, soft tissue reactions,

and general muscle strength. Early failure of joint replacement is associated

with excessive activity and preoperative joint and bone pathology.

Nursing Interventions

Assessment of the

patient and preoperative management are aimed at having the patient in optimal

health at the time of surgery. Pre-operatively, it is important to evaluate

cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and hepatic functions. Age, obesity,

preoperative leg edema, history of DVT, and varicose veins increase the risk of

post-operative DVT and pulmonary embolism. These are the most com-mon causes of

postoperative mortality for patients older than 60 years of age undergoing

total hip replacement. Every effort is made to prevent these complications.

Preoperatively, it is

important to assess the neurovascular sta-tus of the extremity undergoing joint

replacement. Postoperative assessment data are compared with preoperative

assessment data to identify changes and deficits. For example, an absent pulse

postoperatively is of concern unless the pulse was also absent pre-operatively.

Nerve palsy could occur as a result of surgery.

PREVENTING INFECTION

Preoperative assessment

of the patient for infections, including urinary tract infection, is necessary

because of the risk of post-operative infection. Any infection 2 to 4 weeks

before planned surgery may result in postponement of surgery. Preoperative skin

preparation frequently begins 1 or 2 days before the surgery. Air-borne

bacteria that contaminate the wound at the time of surgery cause most deep

infections. Therefore, as with any surgery, there is strict adherence to

aseptic principles and the operating area is controlled and made as bacteria

free as possible.

Prophylactic antibiotics are administered perioperatively

as a single preoperative or short perioperative course (Rosen et al., 1999).

Culture of the joint during surgery, before intraoperative antibiotic therapy

is begun, may be important in identifying and treating subsequent infections.

If osteomyelitis develops, it is difficult to treat.

Persistent in-fection at the site of the prosthesis usually requires removal of

the implant and joint revision, which is a complex procedure. Also, it is not

always possible to achieve a functional joint when the re-construction

procedure has to be repeated.

PROMOTING AMBULATION

Patients with total hip

or total knee replacement begin ambu-lation with a walker or crutches within a

day after surgery. The nurse and the physical therapist assist the patient in

achieving the goal of independent ambulation. At first, the patient may only be

able to stand for a brief period because of orthostatic hypoten-sion. Specific

weight-bearing limits on the prosthesis are deter-mined by the physician and

are based on the patient’s condition, the procedure, and the fixation method.

Usually, patients with cemented prostheses can proceed to weight bearing as

tolerated. If the patient has a press-fit, cementless, ingrowth prosthesis,

weight bearing immediately after surgery may be limited to min-imize

micromotion of the prosthesis in the bone. As the patient is able tolerate more

activity, the nurse encourages transferring to a chair several times a day for

short periods and walking for pro-gressively greater distances.

Related Topics