Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Management of Patients with Fluid & Electrolyte Disturbances

Hypocalcemia

HYPOCALCEMIA

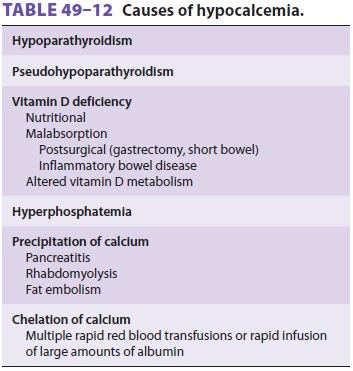

Hypocalcemia should be diagnosed only on the basis of the plasma ionized

calcium concentration. When direct measurements of plasma [Ca2+] are not available, the total

calcium concentration must be corrected for decreases in plasma albumin

concen-tration (see above). The causes of hypocalcemia are listed in Table

49–12.

Hypocalcemia due to hypoparathyroidism is a relatively common cause of

symptomatic hypocal-cemia. Hypoparathyroidism may be surgical, idio-pathic,

part of multiple endocrine defects (most often with adrenal insufficiency), or

associated with hypomagnesemia. Magnesium deficiency may impair the secretion

of PTH and antagonize the effects of PTH on bone. Hypocalcemia during sep-sis

is also thought to be due to suppression of PTH release. Hyperphosphatemia is also a relatively common cause of

hypocalcemia, particu-larly in patients with chronic renal failure.

Hypo-calcemia due to vitamin D deficiency may be the result of a markedly

reduced intake (nutritional), vitamin D malabsorption, or abnormal vitamin D

metabolism.

Chelation of calcium ions with the citrate ions in blood preservatives

is an important cause of perioperative hypocalcemia in transfused patients;

similar transient decreases in [Ca 2+] are also pos-sible following

rapid infusions of large volumes of albumin. Hypocalcemia following acute

pancreati-tis is thought to be due to precipitation of calcium with fats

(soaps) following the release of lipolytic enzymes and fat necrosis;

hypocalcemia following fat embolism may have a similar basis. Precipitation of

calcium (in injured muscle) may also be seen fol-lowing rhabdomyolysis.

Less common causes of hypocalcemia include calcitonin-secreting

medullary carcinomas of the thyroid, osteoblastic metastatic disease (breast

and prostate cancer), and pseudohypoparathyroidism (familial unresponsiveness

to PTH). Transient hypo-calcemia may be seen following heparin, protamine, or

glucagon administration.

Clinical Manifestations of Hypocalcemia

Manifestations of hypocalcemia include

paresthe-sias, confusion, laryngeal stridor (laryngospasm), carpopedal spasm

(Trousseau’s sign), masseter spasm (Chvostek’s sign), and seizures. Biliary

colic and bronchospasm have also been described. ECG may reveal cardiac

irritability or QT interval pro-longation, which may not correlate in severity

with the degree of hypocalcemia. Decreased cardiac con-tractility may result in

heart failure, hypotension,or both. Decreased responsiveness to digoxin and

β-adrenergic agonists may also occur.

Treatment of Hypocalcemia

Symptomatic hypocalcemia is a medical

emer-gency and should be treated immediately withintravenous calcium chloride

(3–5 mL of a 10% solu-tion) or calcium gluconate (10–20 mL of a 10% solu-tion).

(Ten milliliters of 10% CaCl 2 contains 272 mg of Ca2+, whereas 10 mL of 10%

calcium gluconate contains only 93 mg of Ca2+.) To avoid

precipita-tion, intravenous calcium should not be given with bicarbonate- or

phosphate-containing solutions. Serial ionized calcium measurements are

manda-tory. Repeat boluses or a continuous infusion (Ca 2+ 1–2 mg/kg/h) may be necessary. Plasma magnesium concentration should be

checked to exclude hypo-magnesemia. In chronic hypocalcemia, oral calcium (CaCO3) and vitamin D replacement are usually

necessary.

Anesthetic Considerations

Significant hypocalcemia should be corrected

pre-operatively. Serial ionized calcium levels should be monitored

intraoperatively in patients with a his-tory of hypocalcemia. Alkalosis should

be avoided to prevent further decreases in [Ca2+]. Intravenous cal-cium

may be necessary following rapid transfusions of citrated blood products or

large volumes of albu-min solutions. Potentiation of the negative inotropic

effects of barbiturates and volatile anesthetics should be expected. Responses to

NMBs are inconsistent and require close monitoring with a nerve stimulator.

Related Topics