Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Haematology and clinical Immunology

Human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS - HIV

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS

Definition

AIDS or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome was first described in 1981 following the recognition of a group of homosexual males suffering from pneumocystis pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Two years later the causative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was isolated. Rapid advances in therapy have changed the natural history of the disease however various clinical states are recognised:

· Primary HIV infection/acute HIV infection/acute seroconversion

· Clinical latency, +/− persistent generalised lym phadenopathy (PGL)

· Early symptomatic infection/AIDSrelated com plex/“B symptoms”

· AIDS (criteria include a CD4 cell count below count <0.2 × 109/ L)

· Advanced HIV infection

Centre for Disease Control in the United States (1993).

In the developed world due to combination antiviral therapy, AIDS is very rarely seen except in undiagnosed patients who present with an AIDS defining diagnosis. It is however still a major problem in the developing world.

Incidence/prevalence

Epidemiological data collated by the World Health Organisation suggests that around 34,000 people in the United Kingdom were living with HIV in 2001. In the same year HIV accounted for 460 UK deaths. Worldwide however it is estimated that in 2002 42 million people were living with HIV, almost 35 million of whom live in SubSaharan Africa and South & South East Asia. 3.1 million people worldwide died of HIV and related illnesses in 2002.

Aetiology/pathophysiology

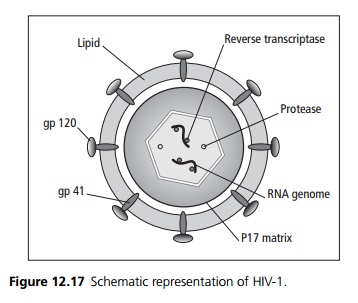

HIV is a retrovirus, an RNA virus that uses a reverse transcriptase enzyme to create a double stranded DNA copy of its genome, which then integrates into the host’s genome. At present two virus families are recognised, HIV-1 and HIV-2 with 40% homology (see Fig. 12.17).

· HIV-1 varies with three genetic groups (M – Major, O - Outlier, N – non-M non-O). The M group is further divided into 10 subgroups (A–J).

· HIV-2 is endemic in West Africa. HIV gains access to cells via a viral surface glycoprotein termed gp120 which interacts with CD4 on helper T lymphocytes and macrophages.

A co-receptor for T-cells and macrophages has been identified as chemokine receptor (CCR5), mutations in which may prevent cell entry and hence give some resistance to viral infection. A similar co-receptor on all lymphoid cells (CXCR4) has also been identified.

Replication cycle

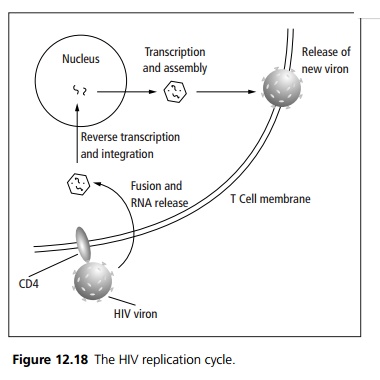

Human infection is usually with macrophage tropic (R5) viruses. HIV infected macrophages then fuse with CD4+ lymphocytes allowing the virus to spread. Once in the blood stream widespread dissemination occurs. An immune response to the virus results in a decrease in detectable viraemia followed by a prolonged period of clinical latency. The CD4+T cell count gradually decreases during this clinical latency, until levels fall to a critical level below which there is a significant risk of opportunist infections.

Following binding between gp120 and CD4 HIV is uncoated and its RNA is released into the cell cytoplasm. The action of viral reverse transcriptase converts the single stranded RNA genome to double stranded DNA, which is then transported to the cell nucleus and inte-grates into the host’s chromosomal DNA. The proviral DNA is then transcribed, translated and the product assembled as if it were a normal cell constituent.

The resulting new viron is then released from the T-cell (see Fig. 12.18).

Transmission is by sexual intercourse (vaginal/anal), vertical transmission, blood products, intravenous drug use or by needle stick injury. Transmission cofactors include viral load, intercurrent sexually transmitted disease, exposure intensity, sexual practices and drug injecting practices.

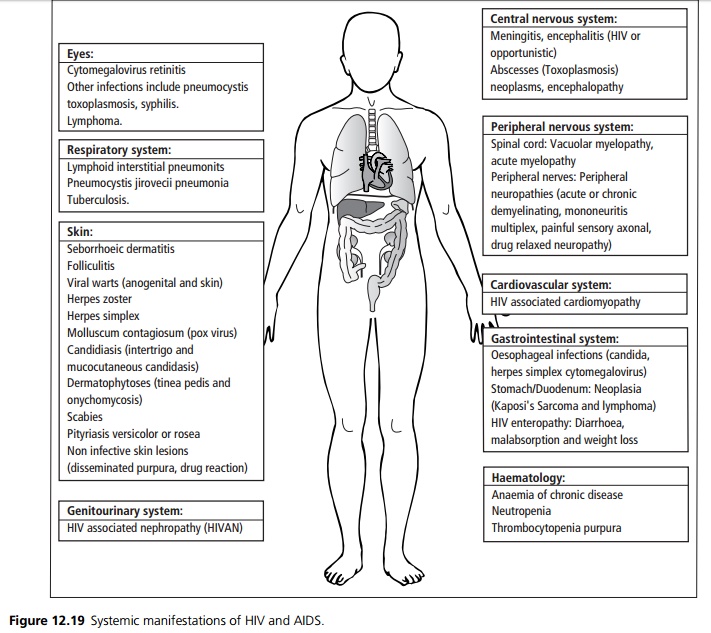

Clinical features

Primary HIV infection/acute HIV infection/acute seroconversion: Many patients are asymptomatic but may develop symptoms 2–8 weeks after exposure with fever, generalised lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, rash, arthralgia, myalgia, diarrhoea, headache, nausea and vomiting. This illness is clinically difficult to distinguish from glandular fever. Rarely a neuropathy or an acute reversible encephalopathy (disorientation, loss of memory, altered personality and conscious level) may occur. These manifes-tations are selflimiting lasting up to 2 weeks from onset.

Clinical latency: Following seroconversion the viral load and CD4 count varies until 6 months when it stabilises at a level correlating with prognosis. During this latent period most patients are asymptomatic, although the majority have symptomless persistent generalised lymphadenopathy (PGL) defined as enlarged lymph nodes involving two or more non-contiguous sites other than the inguinal nodes.

Symptomatic HIV infection and AIDS:

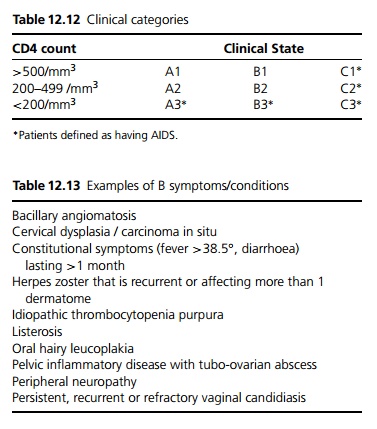

The Centre for Disease Control in the United States has produced a classification for HIV infection based on clinical state and the absolute CD4+ve T cell count (see Table 12.12). The patient’s clinical state is divided into

1. Acute seroconversion/asymptomatic/persistent generalised lymphadenopathy (PGL).

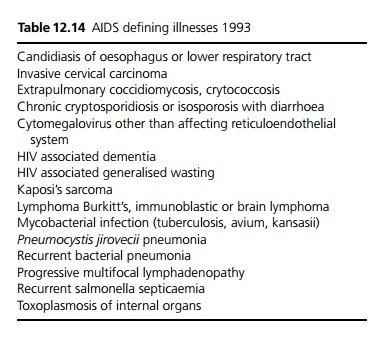

2. Presence of 1 or more B symptoms (see Table 12.13).

3. Presence of an AIDS defining illness (see Table 12.14).

Infections and HIV

Candidiasis: The commonest appearance is of pseudomembranous creamy plaques which may be wiped off (distinguishes from leukoplakia) to reveal a bleeding surface. Infection of the distal oesophagus may cause retrosternal chest pain and dysphagia, or may be asymptomatic. Diagnosis is made on barium swallow or endoscopy. Treatment is with systemic anti-fungals such as fluconazole.

Oral hairy leukoplakia is due to an opportunistic infection with Epstein Barr virus within the oral mucosa. It appears as unilateral whitish plaques on the side of the tongue. In the majority of cases no treatment is required, any coexistent candida should be treated, aciclovir may help although invariably it recurs.

Toxoplasmosis causes encephalitis and abscesses in immunodeficient patients. Infections are due to reactivation of previously acquired infection. Patients present with headache, confusion, personality change, focal neurological signs, seizures and reduced consciousness. Fever may be absent. CT/ MRI shows multiple masses, often with ring enhancement and surrounding oedema. Treatment is with pyrimethamine and sulphadiazine.

Cryptosporidium parvum is transmitted by the faecal oral route and causes watery diarrhoea, colic, nausea, vomiting and a severe fluid/electrolyte loss with severe weight loss. Stool microscopy shows cysts, stained with Ziehl Neelsen stain. Patients require rehydration. There is no satisfactory treatment.

Cryptococcus fungal infection in HIV presents most commonly with meningitis. Patients present with headache, fever, impaired conscious level and abnormal affect. The classical neck stiffness and photophobia are rarely seen. A CT scan should be performed to exclude space occupying lesion prior to lumbar puncture. CSF is stained with Indian ink, serum and CSF antigen titre can be measured, cryptococci may be cultured from CSF and/or blood. Treatment is with iv amphotericin B or fluconazole.

Cytomegalovirus can cause retinitis, colitis, oesophagitis, encephalitis and pneumonitis in HIV infected individuals. Colitis presents as abdominal pain and tenderness often in the left iliac fossa, profuse bloody diarrhoea and low grade fever. Stool culture is used to exclude other causes, endoscopy reveals an inflamed appearance of patchy colitis and vasculitis. Biopsy shows non-specific inflammatory changes, dense round (Owl’s eye) intra-nuclear inclusion bodies in swollen cells. Retinitis may cause blindness and may present as loss of vision, field defect, acuity problems or pain. Eye disease is treated with ganciclovir (myelosupressive) or foscarnet (nephrotoxic) and must be followed by maintenance therapy.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections are usually due to reactivation of latent infection in the context of progressive immunodeficiency. Symptoms may be less specific with fever, weight loss, fatigue and cough. Patients with low CD4 counts frequently have extra-pulmonary disease, e.g. bone marrow, lymph nodes, CNS or liver. Drug resistance (often multiple) is a growing problem.

Mycobacterium avium intracellulare causes infection via the respiratory or GI tract and causes fever, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia and malaise, hepatomegaly, chronic diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Anaemia is common. Treatment is with a four drug combination such as ethambutol, rifabutin, clarithromycin and amikacin.

Patients are at risk of developing lymphomas most commonly non-Hodgkin’s large B cell lymphoma in extranodal sites. These may result from reactivated or latent Epstein Barr virus. Gastrointestinal lym-phoma is the commonest site. Presentation is variable (dysphagia in oesophageal, haematemesis in the gastric, obstruction or perforation in the colon, altered bowel habit and bleeding in rectal lymphomas). Intrathoratic lymphomas cause pleural effusion, mediastinal lymphadenopathy and reticulonodular pulmonary infiltrates. Oral lymphomas may present in the tonsils, alveolus, palate, or cheek regions. Cerebral lymphomas present with encephalopathy, brain stem abnormalities or cranial neuropathy. CT is used for diagnosis. Lymphomas are often refractory to radio-therapy and chemotherapy.

Pneumocystis jirovecii and Kaposi’s sarcoma associated with HIV are covered separately (see below).

Investigations

The detection of IgG antibody against envelope components of the virus is the most commonly used diagnostic test and PCR can be used to detect the virus. The disease is followed using quantitative PCR to determine the viral load, and by the CD4 T cell count.

Management

At present, there is no consensus on whether patients with primary HIV infection should be treated. Antiretrovirals are only of proven benefit in advanced symptomatic disease. In general treatment is commenced if the patient is symptomatic, there is a rapidly falling CD4 count or a high viral load. Three classes of drugs are available:

· Nucleoside-analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as zidovudine, didanosine, zalcitabine and lamivudine.

· Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as nevirapine.

· Protease inhibitors such as ritonavir, indinavir.

In general two nucleoside-analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors with one drug from either of the other two classes are used as first line treatment. Treatment is tailored according to compliance, side effects and the response to treatment.

Prevention strategies include safer sexual practice (reducing the number of sexual partners, use of barrier contraception), needle exchange programmes, screening of donor blood, semen and organs. Strategies to reduce vertical transmission include screening, caesarean delivery, maternal and neonatal anti-retroviral treatment and avoidance of breast-feeding. Health-care workers also require education, careful disposal of sharps and prophylaxis following needle stick injuries.

Prognosis

Untreated the life expectancy of an HIV infected individual is approximately 10 years. A few individuals are classified as longterm non-progressors with normal CD4 counts and low viral load in the absence of treatment. Prognosis has been dramatically improved by combination antiretroviral therapy, and life expectancy is likely to be more than doubled by this treatment.

Related Topics