Chapter: Essential Microbiology: Microbial Genetics

How do we know genes are made of DNA?

How do we know

genes are made of DNA?

The concept of the gene as an inherited physical

entity determining some aspect of an organism’s phenotype dates back to the

earliest days of genetics. The question of what genes are actually made of was

a major concern of molecular biologists (not that they would have described

themselves as such!) in the first half of the 20th century. Since it was

recognised by this time that genes must be located on chromosomes, and that

chromosomes (in eucaryotes) comprised largely protein and DNA, the reasonable

assumption was made that genes must be made up of one of these substances. In

the early years, protein was regarded as the more likely candidate, since, from

what was known of molecular structure at the time, it offered far more scope

for the variation which would be essential to account for the thousands of

genes that any organism must possess. The road to proving that DNA is in fact

the ‘stuff of life’ was a long and hard one, which can be read about elsewhere;

we shall mention below just some of the key experiments which provided crucial

evidence.

In 1928 the Englishman Fred Griffith carried out a

seminal series of experiments which not only demonstrated for the first time

the phenomenon of genetic transfer in bacteria (a subject we shall consider in

more detail later), but also acted as the first step towards proving that DNA

was the genetic material. As we shall see, Griffith showed that it was possible

for heritable characteristics to be transferred from one type of bacterium to

another, but the cellular component responsible for this phenomenon was not

known at this time.

Attempts were made throughout the 1930s to isolate

and identify the transform-ing principle,

as it became known, and in 1944 Avery, MacLeod and McCarty pub-lished a paper,

which for the first time, proposed DNA as the genetic material. Avery and his

colleagues demonstrated that when DNA was rendered inactive by enzy-matic

treatment, transforming ability was lost from a cell extract, but if proteins,

carbohydrates or any other cellular component was similarly inactivated, the

ability was retained. In spite of this apparently convincing proof, the pro-protein

lobby was not easily persuaded. It was to be several more years before the

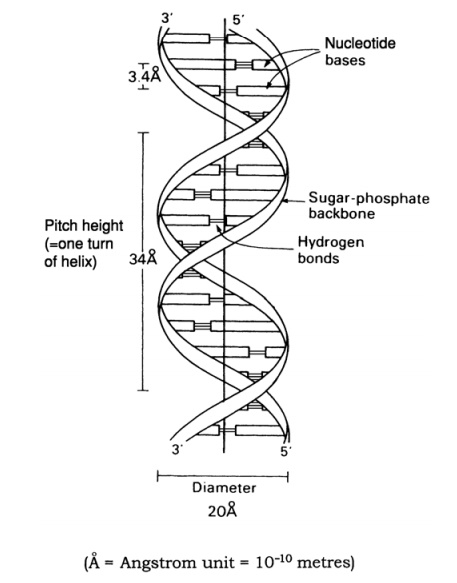

experimental results of Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase coupled with Watson and

Crick’s model for DNA structure (Figure 2.23) finally cemented the universal

acceptance of DNA’s central role in genetics.

Related Topics