Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Drugs Used in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Diseases

H2-Receptor Antagonists - Agents that Reduce Intragastric Acidity

H2-RECEPTOR

ANTAGONISTS

From

their introduction in the 1970s until the early 1990s, H2-receptor

antagonists (commonly referred to as H2

blockers) were the most commonly prescribed drugs in the world (see Clinical

Uses). With the recognition of the role of H

pylori in ulcer disease (which may be treated with appropriate

antibacterial therapy) and the advent of proton pump inhibitors, the use of

prescription H2 blockers has declined markedly.

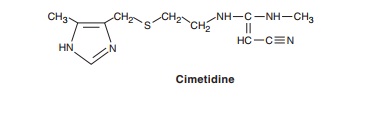

Chemistry & Pharmacokinetics

Four H2 antagonists are in

clinical use: cimetidine, ranitidine, famo-tidine, and nizatidine. All four

agents are rapidly absorbed from the intestine. Cimetidine, ranitidine, and

famotidine undergo first-pass hepatic metabolism resulting in a bioavailability

of approximately 50%. Nizatidine has little first-pass metabolism. The serum

half-lives of the four agents range from 1.1 to 4 hours; however, dura-tion of

action depends on the dose given (Table 62–1). H2 antagonists are cleared by a combination of

hepatic metabolism, glomerular filtration, and renal tubular secretion. Dose

reduction is required in patients with moderate to severe renal (and possibly

severe hepatic) insufficiency. In the elderly, there is a decline of up to 50%

in drug clearance as well as a significant reduction in vol-ume of

distribution.

Pharmacodynamics

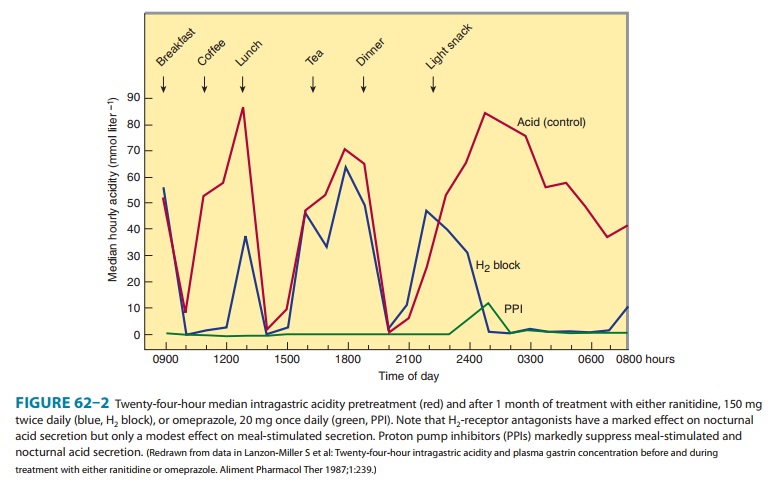

The

H2 antagonists exhibit competitive

inhibition at the parietal cell H2

receptor and suppress basal and meal-stimulated acid secretion (Figure 62–2) in

a linear, dose-dependent manner. They are highly selective and do not affect H1

or H3 receptors . The volume of gastric

secretion and the concentra-tion of pepsin are also reduced.

H2

antagonists reduce acid secretion stimulated by histamine as well as by gastrin

and cholinomimetic agents through two mechanisms. First, histamine released

from ECL cells by gastrin or vagal stimulation is blocked from binding to the

parietal cell H2 receptor. Second, direct

stimulation of the parietal cell by gastrin or acetylcholine has a diminished

effect on acid secretion in the presence of H2-receptor

blockade.

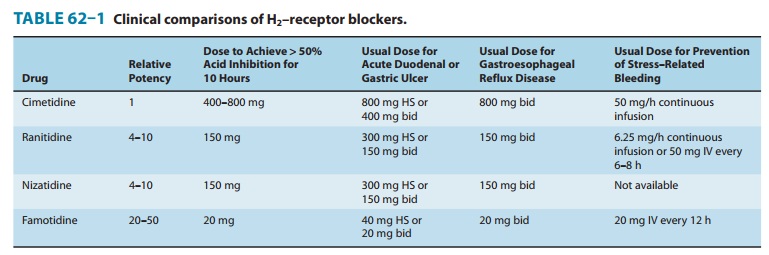

The potencies of the

four H2-receptor antagonists

vary over a 50-fold range (Table 62–1). When given in usual prescription doses

however, all inhibit 60–70% of total 24-hour acid secretion. H2 antagonists are

especially effective at inhibiting nocturnal acid secretion (which depends

largely on histamine), but they have a modest impact on meal-stimulated acid

secretion (which is stimu-lated by gastrin and acetylcholine as well as

histamine). Therefore, nocturnal and fasting intragastric pH is raised to 4–5

but the impact on the daytime, meal-stimulated pH profile is less. Recommended

prescription doses maintain greater than 50% acid inhibition for 10 hours;

hence, these drugs are commonly given twice daily. At doses available in

over-the-counter formulations, the duration of acid inhibition is less than 6

hours.

Clinical Uses

H2-receptor antagonists

continue to be prescribed but proton pump inhibitors are steadily replacing H2 antagonists for most

clinical indications. However, the over-the-counter preparations of the H2 antagonists are

heavily used by the public.

A. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Patients

with infrequent heartburn or dyspepsia (fewer than 3 times per week) may take

either antacids or intermittent H2

antagonists. Because antacids provide rapid acid neutralization, they afford

faster symptom relief than H2

antagonists. However, the effect of antacids is short-lived (1–2 hours)

compared with H2 antagonists (6–10 hours). H2

antagonists may be taken prophylac-tically before meals in an effort to reduce

the likelihood of heart-burn. Frequent heartburn is better treated with

twice-daily H2 antagonists (Table 62–1) or proton

pump inhibitors. In patients with erosive esophagitis (approximately 50% of

patients with GERD), H2

antagonists afford healing in less than 50% of patients; hence proton pump

inhibitors are preferred because of their superior acid inhibition.

B. Peptic Ulcer Disease

Proton pump inhibitors

have largely replaced H2 antagonists in the treatment of acute peptic ulcer disease.

Nevertheless, H2 antagonists are still

sometimes used. Nocturnal acid suppression by H2 antagonists affords effective ulcer healing

in most patients

Pharmacodynamics

The H2

antagonists exhibit competitive inhibition at the parietal cell H2

receptor and suppress basal and meal-stimulated acid secretion (Figure 62–2) in

a linear, dose-dependent manner. They are highly selective and do not affect H1

or H3 receptors . The volume of gastric

secretion and the concentra-tion of pepsin are also reduced.

H2

antagonists reduce acid secretion stimulated by histamine as well as by gastrin

and cholinomimetic agents through two mechanisms. First, histamine released

from ECL cells by gastrin or vagal stimulation is blocked from binding to the

parietal cell H2 receptor. Second, direct

stimulation of the parietal cell by gastrin or acetylcholine has a diminished

effect on acid secretion in the presence of H2-receptor

blockade.

The

potencies of the four H2-receptor

antagonists vary over a 50-fold range (Table 62–1). When given in usual

prescription doses however, all inhibit 60–70% of total 24-hour acid secretion.

H2 antagonists are especially

effective at inhibiting nocturnal acid secretion (which depends largely on

histamine), but they have a modest impact on meal-stimulated acid secretion

(which is stimu-lated by gastrin and acetylcholine as well as histamine).

Therefore, nocturnal and fasting intragastric pH is raised to 4–5 but the

impact on the daytime, meal-stimulated pH profile is less. Recommended

prescription doses maintain greater than 50% acid inhibition for 10 hours;

hence, these drugs are commonly given twice daily. At doses available in

over-the-counter formulations, the duration of acid inhibition is less than 6

hours.

Clinical Uses

H2-receptor antagonists continue to be

prescribed but proton pump inhibitors

are steadily replacing H2 antagonists for most clinical indications. However, the

over-the-counter preparations of the H2 antagonists are heavily used by the public.

A. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Patients

with infrequent heartburn or dyspepsia (fewer than 3 times per week) may take

either antacids or intermittent H2

antagonists. Because antacids provide rapid acid neutralization, they afford

faster symptom relief than H2

antagonists. However, the effect of antacids is short-lived (1–2 hours)

compared with H2 antagonists (6–10 hours). H2

antagonists may be taken prophylac-tically before meals in an effort to reduce

the likelihood of heart-burn. Frequent heartburn is better treated with

twice-daily H2 antagonists (Table 62–1) or proton

pump inhibitors. In patients with erosive esophagitis (approximately 50% of

patients with GERD), H2

antagonists afford healing in less than 50% of patients; hence proton pump

inhibitors are preferred because of their superior acid inhibition.

B. Peptic Ulcer Disease

Proton pump inhibitors have largely replaced H2 antagonists in the treatment of acute peptic ulcer disease. Nevertheless, H2 antagonists are still sometimes used. Nocturnal acid suppression by H2 antagonists affords effective ulcer healing in most patients with uncomplicated gastric and duodenal ulcers. Hence, all the agents may be administered once daily at bedtime, resulting in ulcer healing rates of more than 80–90% after 6–8 weeks of therapy. For patients with ulcers caused by aspirin or other NSAIDs, the NSAID should be discontinued. If the NSAID must be continued for clinical reasons despite active ulceration, a pro-ton pump inhibitor should be given instead of an H2 antagonist to more reliably promote ulcer healing. For patients with acute peptic ulcers caused by H pylori, H2 antagonists no longer play a significant therapeutic role. H pylori should be treated with a 10-to 14-day course of therapy including a proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics . This regimen achieves ulcer heal-ing and eradication of the infection in more than 90% of patients. For the minority of patients in whom H pylori cannot be success-fully eradicated, H2 antagonists may be given daily at bedtime in half of the usual ulcer therapeutic dose to prevent ulcer recurrence (eg, ranitidine, 150 mg; famotidine, 20 mg).

C. Nonulcer Dyspepsia

H2 antagonists are commonly used as

over-the-counter agents and prescription agents for treatment of intermittent

dyspepsia not caused by peptic ulcer. However, benefit compared with placebo

has never been convincingly demonstrated.

D. Prevention of Bleeding from Stress-Related Gastritis

Clinically important bleeding from upper

gastrointestinal erosions or ulcers occurs in 1–5% of critically ill patients

as a result of impaired mucosal defense mechanisms caused by poor perfusion.

Although most critically ill patients have normal or decreased acid secretion,

numerous studies have shown that agents that increase intragastric pH (H2 antagonists or proton

pump inhibitors) reduce the incidence of clinically significant bleeding.

However, the opti-mal agent is uncertain at this time. For patients without a

nasoen-teric tube or with significant ileus, intravenous H2 antagonists are

preferable over intravenous proton pump inhibitors because of their proven

efficacy and lower cost. Continuous infusions of H2 antagonists are generally preferred to bolus

infusions because they achieve more consistent, sustained elevation of

intragastric pH.

Adverse Effects

H2 antagonists are extremely safe drugs. Adverse

effects occur in less than 3% of patients and include diarrhea, headache,

fatigue, myalgias, and constipation. Some studies suggest that intravenous H2 antagonists (or

proton pump inhibitors) may increase the risk of nosocomial pneumonia in

critically ill patients.

Mental status changes (confusion,

hallucinations, agitation) may occur with administration of intravenous H2 antagonists,

especially in patients in the intensive care unit who are elderly or who have

renal or hepatic dysfunction. These events may be more common with cimetidine.

Mental status changes rarely occur in ambulatory patients.

Cimetidine inhibits binding of

dihydrotestosterone to andro-gen receptors, inhibits metabolism of estradiol,

and increases serum prolactin levels. When used long-term or in high doses, it

may cause gynecomastia or impotence in men and galactorrhea in women. These

effects are specific to cimetidine and do not occur with the other H2 antagonists.

Although there are no known harmful effects on

the fetus, H2 antagonists cross the

placenta. Therefore, they should not be administered to pregnant women unless

absolutely necessary. The H2 antagonists are secreted into breast milk and may therefore

affect nursing infants.

H2 antagonists may rarely cause blood

dyscrasias. Blockade of cardiac H2 receptors may cause bradycardia, but this is rarely of clinical

significance. Rapid intravenous infusion may cause brady-cardia and hypotension

through blockade of cardiac H2 receptors; therefore, intravenous injections should be given

over 30 minutes. H2 antagonists rarely cause reversible abnormalities in liver

chemistry.

Drug Interactions

Cimetidine interferes with several important

hepatic cytochrome P450 drug metabolism pathways, including those catalyzed by

CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 . Hence, the half-lives of drugs metabolized

by these pathways may be prolonged. Ranitidine binds 4–10 times less avidly

than cime-tidine to cytochrome P450. Negligible interaction occurs with

nizatidine and famotidine.

H2 antagonists compete with creatinine and

certain drugs (eg, procainamide) for renal tubular secretion. All of these

agents except famotidine inhibit gastric first-pass metabolism of ethanol,

especially in women. Although the importance of this is debated, increased

bioavailability of ethanol could lead to increased blood ethanol levels.

Related Topics