Chapter: Psychology: Intelligence

Group Differences in IQ: Stereo Type Threat

STEREO

TYPE THREAT

In

the previous section, we asked whether blacks’ and whites’ IQ scores would be

the same if we could match their environments. If the answer is yes, then this

obviously points toward an environmental explanation of the race difference.

But to tackle this question in a thorough way, it may not be enough to match

factors like parental educa-tion, income, and occupational level. Even if we

succeed in matching for these aspects of life, black and white children still

grow up in different environments. This is because, after all, black children

grow up knowing they are black and knowing a lot about what life paths are

easily open to them and what life paths are likely. White children

corre-spondingly grow up knowing they are white, and they too have a sense of what

life paths are open or likely. Moreover, each group, because of the color of

their skin, is treated differently by the people in their social environment.

In these ways, their envi-ronments and experiences are not matched—even if the

parents have similar jobs and similar income levels, and even if the children

have similar educational experiences.

Do

these social experiences matter for intelligence scores? As one indication that

they do, consider studies of stereotype

threat, a term used to describe the negative impact that social

stereotypes, once activated, can have on task performance. Here’s an example:

Imagine an African American is taking an intelligence test. She might well

become anxious because she believes this is a test on which she is expected to

do poorly. This anxiety might then be compounded by the thought that her poor

performance will only serve to confirm others’ prejudices. These feelings, of

course, could then easily erode performance by making it more difficult for her

to pay atten-tion and do her best work. Moreover, given the discouraging

thought that poor performance is inevitable, she might well decide not to

expend enormous effort—if she’s likely to do poorly, why struggle against the

tide?

Evidence

for these effects comes from various studies, including some in which two

groups of African Americans are given exactly the same test. One group is told,

at the start, that the test is designed to assess their intelligence; the other

group is led to believe that the test is simply composed of challenges and is

not designed to assess them in any way. The first group, for which the

instructions trigger stereotype threat, does markedly worse (C. Steele, 1998;

C. Steele & Aronson, 1995).

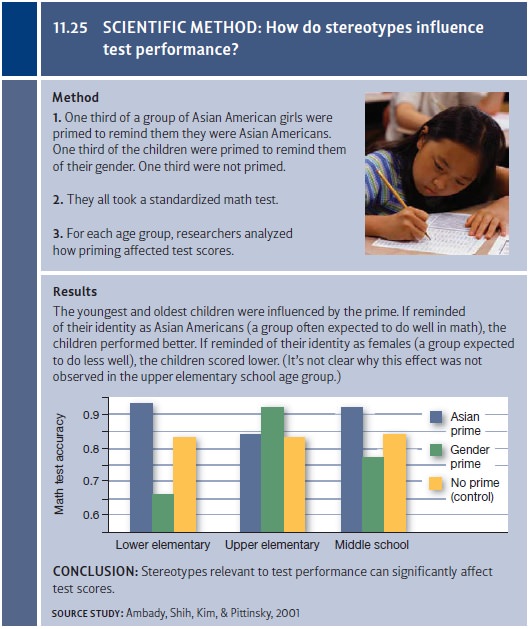

Related

results have been shown in many other circumstances and have been demon-strated

with children as well as adults. Similar data have also been reported for

groups other than African Americans, and in fact stereotype threat is plainly

relevant to our pre-vious discussion of comparisons between men and women

(Blascovich, Spencer, Quinn,Steele, 2001; Cheryan & Bodenhausen, 2000). For example (and as we mentioned

earlier), merely reminding test takers of their gender just before they take a

math test seems to encourage women to think about the stereotype that women

cannot do math, and this seems to undermine their test performance. This is

because thoughts about the stereotype increase the women’s anxiety about the

test, cut into the likelihood that they’ll work as hard as they can, and make

it less likely that they’ll persevere if the test grows frustrating (Ambady,

Shih, Kim, & Pittinsky, 2001, Figure 11.25). A different study had students

read an essay that argued that gender differences in math performance have

genetic causes; women who read this essay then performed more poorly on a math

test than did women who read essays on other topics (Dar-Nimrod & Heine,

2006). Presumably, the essay on genetic causes was demoralizing to the women

and made them more vulnerable to stereotype threat—and therefore undermined

their test performance.

Conversely,

some interventions can improve performance, presumably by dimin-ishing the

anxiety and low self-expectations associated with stereotype threat. In one

study, middle-school students were asked to write brief essays—just a few

sentences—about things they valued. The participants were given a list of

possible values to choose from: “athletic ability, being good at art, being

smart, creativity” and so on (G. Cohen, Garcia, Apfel, & Master, 2006;

Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel, & Brzustoski, 2009). This brief

exercise was then repeated periodically during the school year; and this was

enough to shift the students’ perspective, getting them to focus on things they

valued rather than school-based anxieties. In fact, the brief intervention

improved the school grades of African American seventh-graders by a striking

40%, markedly reducing the difference between white students’ and black

students’ grades. Remarkably, effects of the intervention were still detectable

in a follow-up study with the same students, two years later.

These results draw our attention back to our earlier comments about what intelligence is—or, more broadly, what it is that “intellectual tasks” require. One requirement, of course, is a set of cognitive skills and capacities (e.g., mental speed, or working memory). A different requirement is the proper attitude toward testing—and the wrong attitude (anxiety about failing, fear of confirming other’s negative expectations) can plainly undermine performance. This is why performance levels can be changed merely by priming people to think of themselves as members of a certain group—whether that group is women, Asians, or African Americans. In this way, social pressures and prejudice can powerfully shape each person’s performance—and can, in particular, contribute to the differences between IQ scores for whites and blacks.

Related Topics