Chapter: Psychology: Intelligence

Intelligence Beyond the IQ Test

INTELLIGENCE BEYOND

THE IQ

TEST

We’ve

now made good progress in filling in our portrait of intelligence. We know that

we can speak of intelligence in general; the psychometric data tell us that. We

also know how to distinguish some more specific forms of intelligence

(linguistic, quantitative, spatial; fluid, crystallized). And, finally, we know

some of the elements that give someone a higher or lower g—namely, mental speed, working memory capacity, and executive

control.

We

might still ask, though, whether there are aspects of intelligence not included

in this portrait—aspects that are somehow separate from the capacities we

measure with our conventional intelligence tests. For example, you probably

know people who are “street-smart” or “savvy,” but not “school-smart.” Such

people may lack the sort of ana-lytic skill required for strong performance in

the classroom, but they’re sophisticated and astute in dealing with the

practical world. Likewise, what about social competence—the ability to persuade

others and to judge their moods and desires? Shrewd salespeople have this

ability, as do successful politicians, quite independent of whether they have

high or low IQ scores.

A

number of studies have explored these other nonacademic forms of intelligence.

For example, one study focused on gamblers who had enormous experience in

betting on horse races and asked them to predict the outcomes and payoffs in

several upcom-ing races. This is a tricky mental task that involves highly

complex reasoning. Factors like track records, jockeys, and track conditions

all have to be remembered and weighed against one another. On the face of it,

the ability to perform such mental calculations seems to be part of what

intelligence tests should measure. But the results proved otherwise; the

gamblers’ success turned out to be completely unrelated to their IQs (Ceci

& Liker, 1986). These findings and others have persuaded researchers that

we need to broaden our conception of intelligence and consider forms of

intelligence that aren’t measured by the IQ test.

Practical Intelligence

One

prominent investigator, Robert Sternberg, has argued that we need to

distinguish several types of intelligence. One type, analytic intelligence, is measured by standard intelligence tests.

A different type is practical

intelligence, needed for skilled reasoning in the day-to-day world

(Sternberg, 1985; also see Henry, Sternberg, & Grigorenko, 2005; Sternberg

& Kaufman, 1998; Sternberg, R. Wagner, Williams, & Horvath, 1995; R.

Wagner, 2000; Figure 11.9).

In

one of Sternberg’s studies, business executives read descriptions of scenarios

involving problems similar to those they faced in their professional work. The

executives

also considered various solutions for each problem and rated them on a scale

from 1 (poor solution) to 7 (excellent solution). These ratings were then used

to assess how much tacit knowledge

each of the executives had—that is, practical know-how gleaned from their

everyday experience. The data showed that this measure of tacit knowledge was

predictive of job performance (and so was correlated with on-the-job

performance ratings as well as salary). Crucially, though, measures of tacit

knowledge weren’t correlated with IQ—and so are plainly assessing something

separate from the sorts of “intelligence” relevant to the IQ test (Sternberg

& Wagner, 1993; R. Wagner, 1987; R. Wagner & Sternberg, 1987).

Other

research, however, has challenged the claim that practical intelligence is

independent of analytic intelligence. In one study, for example, measures of

practical intel-ligence were correlated with measures of g (Cianciolo et al., 2006; also see N. Brody, 2003; Gottfredson,

2003a, 2003b; Sternberg, 2003). Even so, many researchers believe that

prac-tical intelligence is different enough from analytic intelligence to

justify separating them in our overall theorizing about people’s different

levels and types of intellectual

ability.

Emotional Intelligence

A

different effort toward broadening the concept of intelligence involves claims

about emotional intelligence—the

ability to understand one’s own emotions and others’,and also the ability to

control one’s emotions when appropriate. The term emotionalintelligence might seem an oxymoron, based on the widely

held view that emotions often undermine our

ability to think clearly and so work against our ability to reason

intelli-gently. Many psychologists, however, reject this claim. They argue that

emotion plays an important role in guiding our problem solving and decision

making (see, for example, Bechara, H. Damasio, & A. Damasio, 2000; A.

Damasio, 1994); emotion also plays a role in guiding our attention and shaping

what we remember (Reisberg & Hertel, 2004). In these ways, emotion and

cognition interact and enrich each other in impor-tant ways.

One

theory suggests that emotional intelligence actually has four parts. First,

there’s an ability to perceive emotions accurately—so that, for example, you

can tell when a friend is tense or when someone is becoming angry. Second,

there’s an ability to use emotions to facilitate thinking and reasoning,

including a capacity to rely on your “gut feelings” in guiding your own

decisions. Third, there’s an ability to understand emo-tions, including the use

of language to describe emotions, so that you’re alert to how a friend will act

when she’s sad or to how fear can alter someone’s perspective; also included

here is the ability to talk about emotions—to convey to others how you’re

feel-ing and to understand what they tell you about their feelings. Finally,

there’s an ability to manage emotions in oneself and others; this includes the

ability to abide by your cul-ture’s rules for “displaying” emotions as well as

the ability to regulate your own emo-tions.

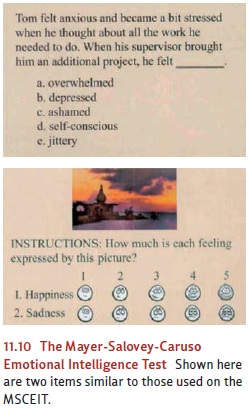

Researchers

have developed various measures of emotional intelligence, including the

Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Bracket & Mayer,

2003; Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, 2003; Figure 11.10). This

measure appears to have predictive validity so that, for example, people who

score higher on the MSCEIT seem to be more successful in social settings. They

have fewer conflicts with their peers, are judged to create a more positive

atmosphere in the workplace, are more tolerant of stress, and are judged to

have more leadership potential (Lopes, Salovey, Côté, & Beers, 2005; Grewal

& Salovey, 2005). Likewise, college students with higher

MSCEIT

scores are rated by their friends as more caring and more supportive. They are

also less likely to experience conflict with their peers (Brackett & Mayer,

2003; Mayer et al., 2008a).

The

idea of emotional intelligence has received much attention in the media and

popular literature; as a result, various claims have been offered in the media

that are not supported by evidence. (For a glimpse of the relationship between

the science and the mythology here, and some concerns about the idea of

emotional intelligence, see Matthews, Zeidner, & Roberts, 2003, 2005.)

Still, emotional intelligence does seem to matter for many aspects of everyday

functioning, it can be measured, and it is one more way that people differ from

one another in their broad intellectual competence.

The Theory of Multiple Intelligences

It

seems that our measures of g—so-called

general intelligence—may not provide as complete a measurement as we thought.

The capacities measured by g are

surely important, but so are other aspects of intelligence—including practical

intelligence, emotional intelligence, and, according to some authors, social intelligence (see, for exam-ple,

Kihlstrom & Cantor, 2000). Other authors would make this list even longer:

In his theory of multiple intelligences,

Howard Gardner argued for several further types of intelligence (Gardner, 1983,

1998): Three of these are incorporated in most standard intelligence tests: linguistic intelligence,

logical-mathematical intelligence, and spatialintelligence.

But Gardner also argued that we should acknowledge musical intelligence, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence (the ability

to learn and create complex patterns of move-ment), interpersonal intelligence (the ability to understand other

people), intrapersonalintelligence (the

ability to understand ourselves), and

naturalistic intelligence (the abilityto understand patterns in nature).

Gardner

based his argument on several lines of evidence, including studies of patients

with brain lesions that devastate some abilities while sparing others. Thus,

certain lesions will make a person unable to recognize drawings (a disruption

of spatial intelligence), while others will make him unable to perform a

sequence of movements (bodily-kinesthetic intelligence) or will devastate

musical ability (musical intelligence). Gardner concluded from these cases that

each of these capacities is served by a separate part of the brain (and so is

disrupted when that part of the brain is damaged), and therefore each is

distinct from the others.

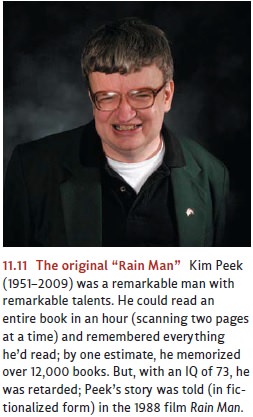

Another

argument for Gardner’s theory comes from the study of people with so-called savant syndrome. These individuals have

a single extraordinary talent, even though they’re otherwise developmentally

disabled (either autistic or mentally retarded) to a profound degree. Some

display unusual artistic talent. Others are “cal-endar calculators,” able to

answer immediately (and correctly!) when asked questions such as “What day of

the week was March 17 in the year 1682?”. Still oth-ers have unusual mechanical

talents or remarkable musical skills—for example, they can effortlessly

memorize lengthy and complex musical works (A. Hill, 1978; L .K .Miller, 1999).

Gardner’s

claims have been controversial, partly because some of the data he cites are

open to other interpretations (see, for example, Cowan & Carney, 2006; L.

K. Miller, 1999; Nettelbeck & Young, 1996; Thioux, Stark, Klaiman, &

Schultz, 2006). In addition, evidence indicates that several of the forms of

“intelligence” Gardner describes are inter-correlated—and so if someone has

what Gardner calls linguistic intelligence, they’re also likely to have

logical-mathematical, spatial, interpersonal, and naturalistic intelligence.

This obviously challenges Gardner’s assertion that these are separate and

independent capacities (Visser, Ashton & Vernon, 2006).

There’s

also room for disagreement about Gardner’s basic conceptualization. Without

question, some individuals—whether savants or otherwise—have special talents; and

these talents are impressive (Figure 11.11). But is it appropriate to think of

these talents as forms of intelligence? Or might we be better served by a

distinction between intelligence and talent? It does seem peculiar to use the

same term, intelligence, to describe

both the capacity that Albert Einstein displayed in developing his theories and

the capacity that Peyton Manning displays on the football field. Similarly, we

might celebrate the vocal tal-ent of Beyoncé Knowles; but is hers the same type

of talent—and therefore sensibly described by the same term, intelligence—that a skilled debater

relies on in rapidly think-ing through the implications of an argument?

Whatever

the ultimate verdict on Gardner’s theory, he has undoubtedly done us a valu-able

service by drawing our attention to a set of abilities that are often ignored

and under-valued. Gardner is surely correct in noting that we tend to focus too

much on the skills and capacities that help people succeed in school, and do

too little to celebrate the talents dis-played by an artist at her canvas, a

skilled dancer in the ballet, or an empathetic clergyman in a hospital room.

Whether these other abilities should be counted as forms of intelli-gence or

not, they’re surely talents to be highly esteemed and, as much as possible,

nur-tured and developed.

The Cultural Context of Intelligence

Yet

another—and perhaps deeper—challenge to our intelligence tests, and a powerful

reason to think beyond the IQ scores, comes from a different source: the

question of whether our tests truly measure intelligence, or whether they

merely measure what’s called intelligence

in our culture.

Different

cultures certainly have different ideas about what intelligence is. For

exam-ple, some parts of the intelligence test put a premium on quick and

decisive responses, but not all cultures share our Western preoccupation with

speed. Indians (of southern Asia) and Native Americans, for example, place a

higher value on being deliberate; in effect, they’d rather be right than quick.

They also prefer to qualify, or to say “I don’t know” or “I’m not sure,” unless

they’re absolutely certain of their answer. Such delib-eration and hedging

would hurt their test scores on many intelligence tests because it’s often a

good idea to guess whenever you’re not sure about the answer (Sinha, 1983;

Triandis, 1989). Similarly, Taiwanese Chinese place a high priority on how they

relate to others; this will, in some circumstances, lead them not to show their

intelligence, thus undermining our standardized assessment (Yang &

Sternberg, 1997; also Nisbett, 2003; for other cultural differences in how

intelligence is defined, see Serpell, 2000; Sternberg, 2004).

These

cultural differences guarantee that an intelligence test that seems appropriate

in one cultural setting may be inappropriate in other cultural settings (Figure

11.12). Moreover, the specific procedure we need for measuring intelligence

also depends on the cultural setting. This is because people in many countries

fail to solve problems that are presented abstractly or that lack a familiar

context, but they do perfectly well with identical problems presented in more

meaningful ways. For example, consider the response of an unschooled Russian

peasant who was asked, “From Shakhimardan to Vuadil it takes three hours on

foot, while to Fergana it is six hours. How much time does it take to go on

foot from Vuadil to Fergana?” The reply was “No, it’s six hours from Vuadil to

Shakhimardan. You’re wrong. . . . It’s far and you wouldn’t get there in three

hours” (Luria, 1976). If this had been a question on a standard intelligence

test, the peasant would have scored poorly—not because he was unintelligent,

but because he did not regard the question as a test of arithmetical reasoning.

It turned out that he was quite able to perform the relevant calculation but

could not accept the form in which the question was presented.

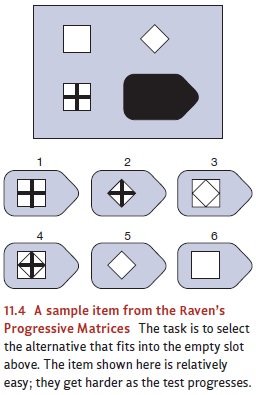

In

light of these concerns, we might well ask whether it’s possible to measure

intel-ligence in a way that’s fair to all cultures and biased against none. The

Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Figure 11.4) are often claimed to be fair to all

groups because the test is nonverbal and doesn’t rely on any sort of specific

prior knowledge. But the very idea of organizing items in rows and columns—an

idea that’s essential for this test—is unfamiliar in some settings, and this

puts test takers in those settings at a disadvantage with this form of testing.

To

put this worry somewhat differently, we could (if we wished) use a standard

intel-ligence test to assess people living in, say, rural Zambia, and the test

results probably would allow us to predict whether the Zambians will do well in

Western schools or in a Western-style workplace. But this form of testing would

tell us nothing about whether these Zambians have the intellectual skills they

need to flourish in their own cultural setting. Just as bad, our test would

probably give us an absurd understatement of the Zambians’ intellectual

competence because our test is simply in the wrong form to reveal that

competence.

Against

this backdrop, it’s important to emphasize that some mental capacities can be

found in all cultures—including (as just one example) the core knowledge needed

to understand some aspects of mathematics (see, for example, Dehaene, Izard,

Pica, & Spelke, 2006). But it’s also clear that cultures differ not only in

the skills they need and value but also in how they respond to our Westernized

test procedures. As a result, we need to be extremely careful in how we

interpret or use our measures of intelligence. Intelligence tests do capture

important aspects of intellectual functioning, but they don’t capture all

aspects or all abilities, and the meaning and utility of the tests has to be

understood in the appropriate cultural context. (For further discussion, see

Greenfield, 1997; Serpell, 2000; Sternberg, 2004.)

Related Topics