Chapter: Psychology: Intelligence

The Roots of Intelligence: Environment and Individual IQ

Environment and Individual IQ

Undeniably,

genetic influences play a powerful role in shaping someone’s intellectual

capacities. Indeed, researchers have begun to explore exactly how these genetic

influ-ences unfold—including an effort to specify which genes, on which

chromosomes, are the ones that shape intelligence. (For glimpses of the modest

progress so far, see Posthuma & deGeus, 2006; Zimmer, 2008.)

As we’ve repeatedly noted, though, genetic effects always unfold within an environ-mental context. So—inevitably—environmental factors also shape the development of our intellect. Evidence for this point comes from many sources; and thus, as we’ll see, the IQ score someone ends up with depends on both her genes and the surroundings in which she grew up.

EFFECTS OF CHANGING THE ENVIRONMENT

The

effect of the environment on IQ scores is evident in many facts. For example,

one Norwegian study examined a huge data set that included intelligence scores

for 334,000 pairs of brothers. The researchers found that the correlation

between the brothers’ intelligence scores was smaller for brothers who were more widely separated in age (Sundet,

Eriksen, & Tambs, 2008). This result is difficult to explain genetically,

because the genetic resemblance is the same for two brothers born, say, one

year apart as it is for two brothers born five years apart. In both cases, the

brothers share 50% of their genetic material. However, this result makes sense

on environmental grounds. The greater the age difference between the brothers,

the more likely it is that the family cir-cumstances have changed between the

years of one brother’s childhood and the years of the other’s. Thus, a greater

age difference would increase the probability that the brothers grew up in

different environments, and to the degree that these environments shape

intelligence, we would expect the more widely spaced brothers to resemble each

other less than the closely spaced siblings.

We’ve

also known for many years that impoverished environments can impede

intel-lectual development. For example, researchers studied children who worked

on canal boats in England during the 1920s and rarely attended school; they

also studied chil-dren who lived in rural mountainous Kentucky, where little or

no schooling was avail-able. These certainly seem like poor conditions for the

development of intellectual skills, and it seems likely that exposure to these

conditions would have a cumulative effect: The longer the child remains in such

an environment, the lower his IQ should be (Figure 11.17). This is precisely

what the data show—a negative correlation between IQ and age. That is, the

older the child (the longer she had been in the impoverished envi-ronment), the

lower her IQ (Asher, 1935; H. Gordon, 1923; also see Heckman, 2006). Related

results come from communities where schools have closed. These closings

typically lead to a decline in intelligence-test scores—in one study, a drop of

about 6 points for every year of school missed (R. L. Green, Hoffman, Morse,

Hayes, & Morgan, 1964; see also Ceci & Williams, 1997; Neisser et al.,

1996).

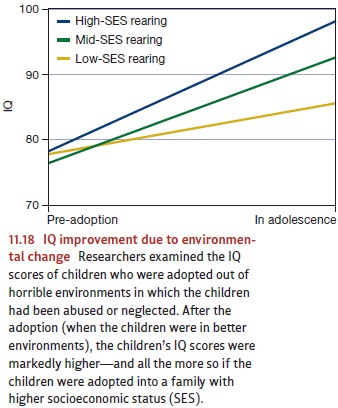

More

optimistically, we also know that improving

the environment can to some extent increase

IQ. For example, in a study in France, researchers focused on cases in

which thegovernment had removed children from their biological parents because

of abuse or neg-lect (Duyme, Dumaret, & Tomkiewicz, 1999) The researchers

were thus able to compare the children’s “pre-adoption IQ” (i.e., when the

children were still living in a high-risk environment) with their IQ in

adolescence—after years of living with their adoptive fam-ilies. The data (Figure

11.18) showed substantial improvements in the children’s scores, thanks to this

environmental change.

A

similar conclusion flows from the effects of explicit training. The Venezuelan

“Project Intelligence,” for example, gave underprivileged ado-lescents in

Venezuela extensive training in various thinking skills (Herrnstein, Nickerson,

de Sanchez, & Swets, 1986). Assessments after training showed substantial

benefits on a wide range of tests. A similar benefit was observed for American

preschool children in the Carolina Abecedarian Project (F. A. Campbell &

Ramey, 1994). These programs leave no doubt that suitable enrichment and

education can provide substantial improvement in intelligence-test scores. (For

still other evidence that schooling lifts intelligence scores, see Ceci &

Williams, 1997; Grotzer & Perkins, 2000; M. Martinez, 2000; Perkins &

Grotzer, 1997.)

We

should note in passing that there’s no conflict between these results and the

results we mentioned earlier when docu-menting the reliability of the IQ test. There we noted that IQ scores are

usually quite stable across the life span, so that (for example) if we know

someone’s IQ at, say, age 10, we can accurately predict what her IQ will be a

decade or more later. This stabil-ity in scores is easily observed if a person lives in a consistent

environment. As we now see, though, changes

in the environment can produce substantial shifts in IQ—by a dozen or more

points. Thus the IQ test is reliable, but this doesn’t mean that IQ scores can’t

change.

WORLD WIDE IMPROVEMENT IN IQ SCORES

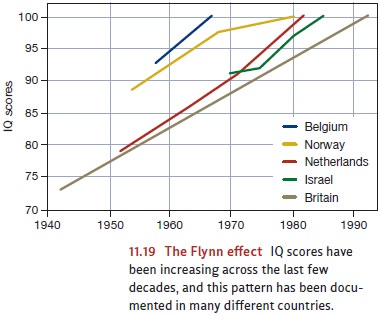

The

impact of environmental factors on IQ scores is also undeniable in another

fact. Around the globe, scores on intelligence tests have been gradually

increasing over the

last few decades,

at a rate

of approximately 3 points

per decade. This

pattern is known

as the Flynn effect, after James R. Flynn (1984, 1987, 1999, 2009; see

also Daley, Whaley, Sigman,

Espinosa, & Neumann,

2003; Kanaya, Scullin, &

Ceci, 2003), one of the first researchers to document this effect systematically. This

improvement has been

documented in many countries,

including many developed (and relatively affluent) nations and also relatively

impoverished third world nations (Figure 11.19). (There’s also some suggestion

that the improvement has now leveled off in some countries—Britain, for

example—and may even be reversing; but it’s too soon to make a judgment on this

point; Flynn, 2009.)

Could

it be that people in the modern world are simply accumulating more and more

information? If so, then the Flynn effect would be most visible in measures of

crystal-lized intelligence. However, that’s not what the evidence shows.

Instead, the effect is stronger in measures of fluid intelligence—such as the

Raven’s Matrices—so it seems to be a genuine change in how quickly and flexibly

people can think.

Some scholars

suggest that this

broad increase in

scores is attributable

to wide- spread improvement in

nutrition and health care, and these factors surely do contribute to the Flynn

effect in some parts of the world (for a study in Kenya, for example, see Daley

et al., 2003). But we need some other explanation for why the effect is also

evi-dent in middle-class populations in relatively wealthy countries (Flynn,

2009). One proposal is that this worldwide improvement is the result of the

increasing complexity and sophistication of our shared culture: Each of us is

exposed to more information and a wider set of perspectives than were our

grandparents, and this exposure may lead to a sharpening of skills that show up

in our data as an improvement in IQ (for a broad discussion, see Dickens &

Flynn, 2001; Greenfield, 2009; Neisser, 1997, 1998).

Whatever

the explanation, though, one point is clear: The Flynn effect cannot be

explained genetically. While the human genome does change (a prerequisite, of

course, for human evolution), it doesn’t change at a pace commensurate with

this effect. Therefore, this worldwide improvement becomes part of the larger

package of evidence documenting that intelligence can indeed be improved by

suitable environ-mental conditions.

THE INTERACTION AMONG GENETIC FACTORS , SES , AND IQ

Let’s

return, though, to the effects of poverty

on IQ , because these effects are informa-tive in two ways. First, these

effects help us understand exactly how the environment shapes intelligence.

Second, these effects also illuminate the interaction

between envi-ronmental and genetic factors in shaping IQ.

The

overall effects of poverty on IQ are easily documented, and in fact there’s a

correlation of .40 between a child’s intelligence scores and the socioeconomic

status of the family in which the child is raised (Lubinski, 2004). Looking

beyond these broad effects, though, we can ask what aspects of intelligence are especially affected as well as how poverty shapes intelligence. We

know, for example, that the impact of poverty isespecially salient in tests of

language skills and also in tasks hinging on executive control (Hackman &

Farah, 2009). In addition, children who live in poverty in their preschool

years seem more at risk than children who live in poverty in middle or late

childhood (G. Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998; Farah et al., 2006).

Apparently, then, many of the harmful effects of poverty aren’t due to inferior

educa-tion. Instead, the effects derive from a mix of other factors, including

exposure to vari-ous toxins found in lower-quality housing, lack of

stimulation, poor nutrition, and inferior health care—and probably also the

chronic stress that goes with poverty. All of these factors can interfere with

the normal development of the brain, and they have important (and deeply

unfortunate) consequences for intellectual functioning. (For more on the

neurocognitive effects of poverty, see Hackman & Farah, 2009.)

These

various problems, all associated with poverty, have a direct effect on brain

development and also interact with genetic influences on development

(Turkheimer, Haley, Waldron, D’Onofrio, & Gottesman, 2003). Specifically,

when researchers focus on higher-SES

families, they find the pattern we’ve already described—an appreciably stronger

resemblance between identical twins’ IQ scores than there is between fraternal

twins’ scores. This tells us (as we’ve discussed) that genetic factors are

playing an important role here, so that people who resemble each other

genetically are likely to resemble each other in their test scores. Among lower-SES families, though, the pattern

is different. In this group, the degree of IQ resemblance is the same for identical and fraternal

twins—which tells us that in this setting, genetic factors seem to matter much

less for shaping a person’s intelligence.

What’s

going on here? Specifically, it may be best to think about our genes as

providing our potential—a capacity to

grow and develop if we’re suitably nurtured. If, therefore, a child receives

good schooling, health care, and adequate nutrition, he’ll be able to develop

this potential; and as the years go by, he’ll be able to make the most of the

genetically defined predisposition he was born with. But if a child grows up in

an impoverished environment with poor schooling, minimal health care, and

inadequate nutrition, it matters much less whether he has a fine

potential—because the environ-ment doesn’t allow the potential to emerge.

Hence, in impoverished environments, genetic factors—the source of the

potential—count for relatively little.

Related Topics