Chapter: Psychology: Intelligence

The Logic of Psychometrics

The Logic of

Psychometrics

We have before us two hypotheses

concerned with the nature of intelligence, and the way we’ve described the

hypotheses points toward the means of deciding which hypothesis is correct.

What we need to do is take a closer look at the IQ tests them-selves and try to

find patterns within the test scores. This kind of scrutiny reflects the psychometric approach to intelligence—an

approach that, at the start, deliberatelyholds theory and definitions to the

side. Instead, it begins with the actual test results and proceeds on the

belief that patterns within these results may be our best guide in deciding

what the tests measure—and therefore what intelligence is. To see how this

works, let’s begin with a hypothetical example.

Imagine that we give a group of

individuals three tests that seem at least initially dif-ferent from each

other; let’s call the tests X, Y, and Z. One hypothesis is that all three tests

measure the same underlying ability—and so, if a person has a lot of this

ability, she has what she needs for all three tests and will do well on all of

them. (This is, of course, the idea that there’s a general ability used for many different tasks.) Based on this

hypothesis, a person’s score on one of these tests should be similar to her

score on the other tests because, whatever the level of ability happens to be,

it’s the same ability that matters

for all three tests. This hypothesis therefore leads to a prediction that there

will be a strong correlation between each person’s score on test X and his or

her score on test Y, and the same goes for X and Z or for Y and Z.

A different hypothesis is that

each of tests X, Y, and Z measures a different abil-ity. This is, of course,

the idea that there’s no such thing as ability in general; instead, each person

has their own collection of more specialized capacities. Based on this view,

it’s possible for a person to have the ability needed for X but not the

abilities needed for Y or Z. It’s also possible for a person to have the

abilities needed for both Y and Z but not those needed for X . It’s possible

for a person to have all of these abilities or none of them. In short, all combinations are possible because

we’re talking about three separate abilities; thus, there is no reason to

expect a cor-relation between someone’s X score and his Y score, or between his

Y score and his Z score, just as there’s no reason to expect a correlation

between, say, someone’s ability to knit well and the size of his vocabulary.

Knitting and knowing a lot of words are simply independent capacities—so you

can be good at one, or the other, or both, or neither.

We could also imagine

intermediary hypotheses: Perhaps X and Y tap into the same, somewhat general

ability, but Z taps into some other, more specialized ability. Perhaps Y and Z

overlap in the abilities relevant for each, but the overlap is only partial.

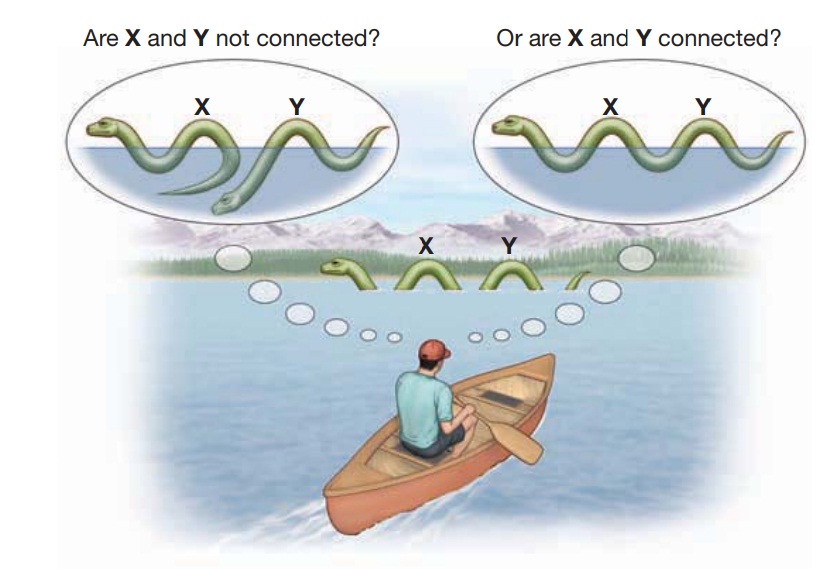

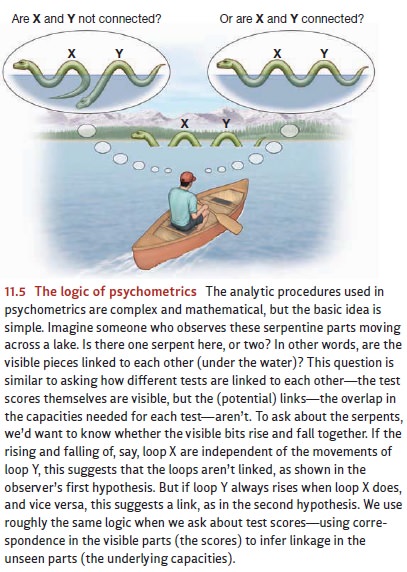

Throughout, however, the logic is the same: If two tests overlap in the

abilities they

require, then they are to some

extent measuring the same thing; so there should be a cor-relation between the

scores on the two tests. If the overlap is slight, the correlation will be

weak; if the overlap is greater, the correlation will be correspondingly

stronger. (For a slightly different—and somewhat whimsical—view of these

points, see Figure 11.5.)

Related Topics