Chapter: Psychology: Intelligence

The Roots of Intelligence: The Politics of IQ Testing

The Politics of IQ Testing

Intelligence testing has been mired in political controversy from the very beginning. Recall that Binet intended his test as a means of identifying schoolchildren who would benefit from extra training. In the early years of the 20th century, however, some people—scientists and politicians—put the test to a different use. They noted the fact (still true today) that there was a correlation between IQ and socioeconomic status (SES): People with lower IQ scores usually end up with lower-paid, lower-status jobs; they’re also more likely to end up as criminals than are people with higher IQs. The politicians therefore asked, why should we try to educate these low-IQ individuals? If we know from the start that those with low intelligence scores are unlikely ever to get far in life, then why waste educational resources on them?

In

sharp contrast, advocates for the disadvantaged took a different view. To begin

with, they often disparaged the tests themselves, arguing that bias built into

the tests favored some groups over others. In addition, they argued that the

connection between IQ and SES was far from inevitable. Good education, they

suggested, can lift the status of almost anyone—and perhaps lift their IQ

scores as well. Therefore, spending educational resources on the poor was an

important priority, especially since it might be the poor who need and benefit

from these resources the most. (For reviews of this history, see S. J. Gould,

1981; Kamin, 1974.)

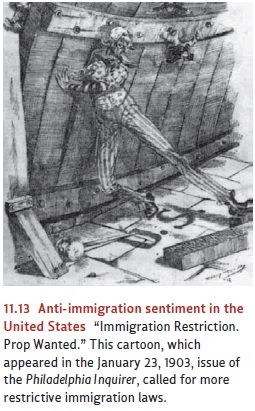

These

contrasting views obviously lead to different prescriptions for social policy,

and for many years, those who viewed low scorers as a waste of resources

dominated the debate. An example is the rationale behind the U.S. immigration

policy between the two World Wars. The immigration act of 1924 (the National

Origins Act) set rigid quotas to minimize the influx of what were thought to be

biologically “weaker stocks”— specifically, immigrants from southern and

eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa. To “prove” the genetic intellectual

inferiority of these immigrants, a congressional committee pointed to the

scores by members of these groups on the U.S. Army’s intelligence test; the

scores were indeed substantially below those attained by Americans of northern

European ancestry (Figure 11.13).

As

it turns out, we now know that these differences among groups, observed in the

early 20th century, were due to the simple fact that the immigrants had been in

the United States for only a short time. Because of their recent arrival, the

immigrants lacked fluency in English and had little knowledge of certain

cultural facts important for doing well on the tests. It’s no surprise, then,

that their test scores were low. After living in the United States for a while,

the immigrants’ U.S. cultural knowledge and English skills improved—and their

scores became indistinguishable from those of native-born Americans. This

observation plainly undermined the hypothesis of a hereditary difference in

intelligence between, say, northern and eastern Europeans, but the proponents

of immigration quotas didn’t analyze the results so closely. They had their own

reasons for restricting immigration, such as fears of competition from cheap

labor. The theory that the excluded groups were innately inferior provided a

convenient justification for their policies (Bronfenbrenner, McClelland,

Wethington, Moen, & Ceci, 1996; Kamin, 1974; W. Williams & Ceci, 1997).

A

more recent example of how intelligence testing can become intertwined with

political and social debate grew out of a highly controversial book—The Bell Curve, by Richard J. Herrnstein

and Charles Murray (1994). This book, and the debate it set off, showcased the

differences among racial groups in their test scores: Whites in the United

States (i.e., Americans of European ancestry) had scores that averaged roughly

10 points higher than the average score for blacks (Americans of African

ancestry). Herrnstein and Murray argued that these differences had important

policy implica-tions, and urged (among other things) reevaluation of programs

that in their view encouraged low-IQ people to have more babies.

Herrnstein

and Murray’s claims were criticized on many counts (e.g., Devlin et al., 1997;

S. Fraser, 1995; R. Jacoby & Glauberman, 1995; R. Lynn, 1999; Montagu,

1999; Neisser et al., 1996; and many more). There has been considerable debate,

for example, about their interpretation of the test scores as well as about

whether “race,” a key con-cept in their argument, is a meaningful biological

category. We’ll return to these points later; for now, it’s enough to note that

these questions have profound political importance, so it’s imperative that we

ensure policy debates are informed by good science.

Related Topics