Chapter: Psychology: Intelligence

Intelligence Testing

INTELLIGENCE TESTING

In 1904,

the French minister

of public instruction

appointed a committee

with the specific task

of identifying children

who were performing

badly in school

and would benefit from

remedial education. One

member of this

committee, Alfred Binet (1857–1911; Figure 11.1), played a

pivotal role and had an extremely optimistic view of the project. As Binet saw

things, the committee’s goal was both to identify the weaker stu- dents and

then—crucially—to improve the students’ performance through training.

Measuring Intelligence

For their

task, Binet and the

other committee members

needed an objective way to

assess each child’s abilities, and in designing their test, they were guided by

the belief that intelligence is a capacity that matters for many aspects of

cognitive functioning. This view led them to construct a test that included a

broad range of tasks varying in content and difficulty: copying a drawing,

repeating a string of digits, understanding a story, arithmetic reasoning, and

so on. They realized that someone might do well on one or two of these tasks

just by luck or due to some specific experience (perhaps theperson had

encountered that story before), but they were convinced that only a

trulyintelligent person would

do well on

all the tasks

in the test. Therefore, intelligencecould be

measured by a composite score that took all the tasks into account.

Moreover,they believed that the diversity of

the tasks ensured that the test was not measuringsome specialized talent

but was instead a measure of ability in general.Indeed, Binet put a heavy

emphasis on this diversity, and even claimedthat, “It matters very little what

the tests are so long as they are numer-ous”.

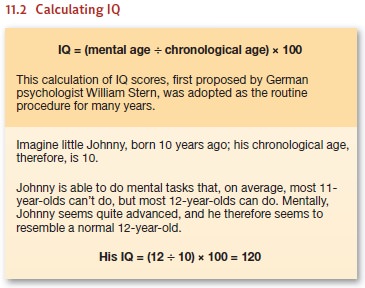

In its original form, the

intelligence test was intended only for chil-dren. The test score was computed

as a ratio between the child’s “mentalage” (the level of development reflected

in the test performance) and hischronological age; the ratio was then

multiplied by 100 to get the finalscore (Figure 11.2). This ratio (or quotient) was the source of the test’sname: The test evaluated the

child’s “intelligence quotient,” or IQ.

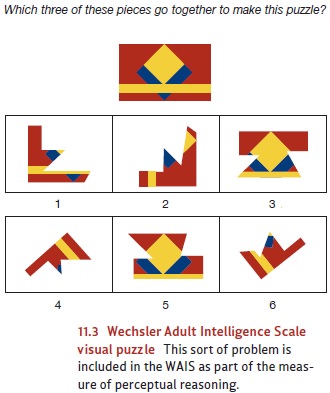

Other, more

recent forms of the test

no longer calculate

a ratiobetween mental and

chronological age, but they’re still called IQ tests.One commonly

used test for

assessing children is the WechslerIntelligence Scale for Children (WISC),

released in its fourth revisionin 2003 (Wechsler, 2003). Adult intelligence is

often evaluated with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS); its fourth

edition was released in 2008. Like Binet’s original test, these modern tests

rely on numerous sub-tests. In the WAIS-IV, for example, there are verbal tests

to assess general knowledge, vocabulary, and comprehension; a

perceptual-reasoning scale includes visual puzzles like the one shown in Figure

11.3. Separate subtests assess working memory and speed of intellectual

processing.

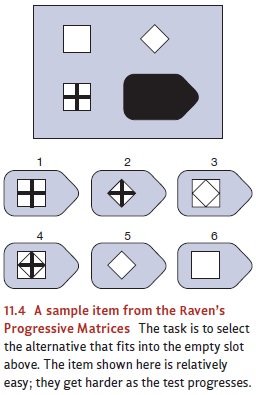

Other intelligence tests have

different formats. For example, the Raven’s Progressive Matrices test (Figure

11.4) contains no subtests and hinges entirely on someone’s ability to analyze

figures and detect patterns. Specifically, this test presents the test taker

with a series of grids (these are the matrices), and she must select an option

that sensibly completes the pattern in each grid. This test is designed to

minimize any influence from verbal skills or back-ground knowledge.

Reliability and Validity

Did Binet (and all who came after

him) succeed in his aim of creating a test that trulymeasures intelligence? To find out, we need to

evaluate the tests’ reliability and validity. As we described there, reliability refers tohow consistent a

measure is in its results and is often evaluated by assessing test-retestreliability. This assessment boils down to a simple

question: If we give the test, wait awhile, and then give it again, do we get

essentially the same outcome?

Intelligence tests

actually have high

test-retest reliability—even if

the two test occasions are

widely separated. For

example, there is

a high correlation

between measurements of someone’s

IQ at, say,

age 6 and

measurements when she’s

18. Likewise, if we know someone’s IQ at age 11, we can predict with

reasonable accuracy what his IQ

will be at age 27

(see, for example,

Deary, 2001a, 2001b;

Deary, Whiteman, Starr, Whalley, & Fox, 2004; Plomin & Spinath,

2004). As it turns out, though, there are some departures from this apparent

stability. For example, a sub- stantial change in someone’s environment can

cause a corresponding change in his IQ score.

Even so, if someone stays in a

relatively stable and healthy environment, IQ tests are quite reliable. What

about validity? This is the crucial evaluation of whether the tests really

meas- ure what we intend them to measure, and one way to approach this issue is

to assess its predictive validity: If the tests truly measure intelligence,

then someone’s score on the test should allow us to predict how well that

person will do in settings that require intelligence. And here, too, the

results are promising. For example, there’s roughly a !.50 correlation between

someone’s IQ and subsequent measures of academic per- formance (e.g.,

grade-point average; e.g., Kuncel, Hezlett, & Ones, 2004; P. Sackett,

Borneman, & Connelly, 2008). This is obviously not a perfect correlation,

because we can easily find lower-IQ students who do well in school, and

higher-IQ students who do poorly. Still, this correlation is strong enough to

indicate that IQ scores do allow us to make predictions about academic

success—as they should, if the scores are valid.

IQ scores are also good predictors

of performance outside the academic

world. In fact, IQ scores are among the strongest predictors of success in the

workplace, whetherwe measure success

subjectively (for example,

via supervisors’ evaluations)

orobjectively (for example, in

productivity or measures

of product quality;

Schmidt &

Hunter, 1998, 2004; P. Sackett et

al., 2008). Sensibly, though, IQ matters more for some jobs than for others.

Jobs of low complex-ity require relatively little intelligence; so, not

surprisingly, the cor-relation between IQ and job performance is small

(although still positive) for such jobs. Thus, for example, there’s a

correlation of roughly .20 between IQ and someone’s performance on an assem-bly

line. As jobs become more complex, intelligence matters more, so the

correlation between IQ and performance gets stronger (Gottfredson, 1997b). Thus

we find correlations between .5 and .6 when we look at IQ scores and people’s

success as accountants or shop managers.

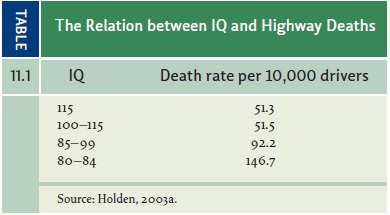

Still other results also confirm

the importance of IQ scores and make it clear that, if we measure someone’s IQ

at a relatively early age, we can use that measure to predict many aspects of

her life to come. For example, people with higher IQ scores tend, overall, to

earn more money during their lifetime, to end up in higher-pres-tige careers,

and even to live longer. Likewise, higher-IQ individuals are less likely to die

in automobile accidents (Table 11.1) and less likely to have difficulty

following a doctor’s instructions. (For a glimpse of this broad data pattern,

see Deary & Derr, 2005; Gottfredson, 2004; Kuncel et al., 2004; Lubinski,

2004; C. Murray, 1998.)

We should emphasize that, as with

the correlation between IQ and grades, all of these correlations between IQ and

life outcomes are appreciably lower than !1.00. This reflects the simple

fact that there are exceptions to the pattern we’re describing— and so some

low-IQ people end up in high-prestige jobs, and some high-IQ people end up

unsuccessful in life (with lousy jobs, low salaries, and a short life

expectancy). These exceptions remind us that (of course) intelligence is just

one of the factors influencing life outcomes—and so, inevitably, the

correlation between IQ and life success isn’t perfect. Nonetheless, there’s

still a strong statistical linkage between IQ scores and important life

outcomes, making it clear that IQ tests do measure something interesting and

consequential.

Related Topics