Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Burn Injury

Emergent/Resuscitative Phase of Burn Care

EMERGENT/RESUSCITATIVE PHASE OF BURN CARE

On-the-Scene Care

Anyone who encounters a burn victim for the first

time may feel overwhelmed. The burned person’s appearance can be frighten-ing

at first. It can be difficult not to get caught up with the ap-pearance of the

person and instead to concentrate on the burn wounds. However, the burn wound

is not the first priority at the scene: the first priority of on-the-scene care

for a burn victim is to prevent injury to the rescuer. If needed, fire and

emergency medical services should be requested at the first opportunity.

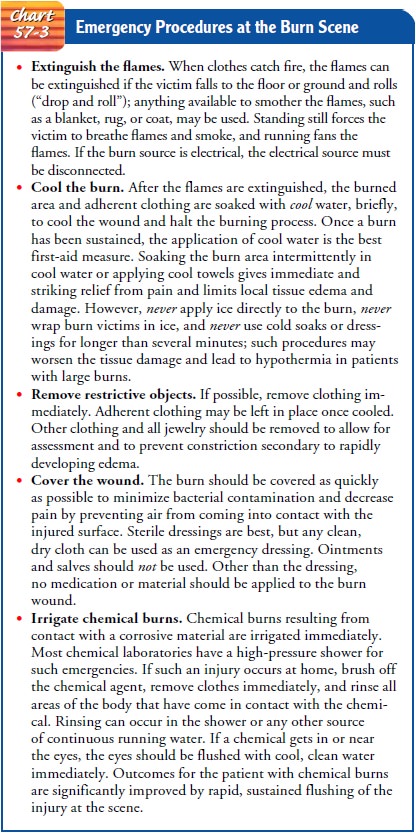

Ad-ditional emergency procedures are highlighted in Chart 57-3.

AIRWAY, BREATHING, CIRCULATION

Although

the local effects of a burn are the most evident, the sys-temic effects pose a

greater threat to life. Therefore, it is impor-tant to remember the ABCs of all

trauma care during the early postburn period:

·

Airway

·

Breathing

·

Circulation; cervical spine

immobilization for patients with high-voltage electrical injuries and if

indicated for other in-juries; cardiac monitoring for patients with all

electrical in-juries for at least 24 hours after cessation of dysrhythmia

Some

practitioners include “DEF” in the trauma assessment: disability, exposure, and

fluid resuscitation (Weibelhaus & Hansen, 2001).

The circulatory system must also be assessed

quickly. Apical pulse and blood pressure are monitored frequently. Tachycardia

(abnormally rapid heart rate) and slight hypotension are expected soon after

the burn. The neurologic status is assessed quickly in the patient with

extensive burns. Often the burn patient is awake and alert initially, and vital

information can be obtained at that time. A secondary head-to-toe survey of the

patient is carried out to identify other potentially life-threatening injuries.

(The E and F parameters of trauma assessment are discussed in detail later.)

Preventing shock in a burn patient is imperative.

Usually, rescue workers will cool the wound, establish an air-way, supply oxygen, and insert at least one large-bore intravenous line.

Emergency Medical Management

The

patient is transported to the nearest emergency depart-ment. The hospital and

physician are alerted that the patient is en route to the emergency department

so that life-saving measures can be initiated immediately by a trained team.

Initial

priorities in the emergency department remain air-way, breathing, and

circulation. For mild pulmonary injury, in-spired air is humidified and the

patient is encouraged to cough so that secretions can be removed by suctioning.

For more se-vere situations, it is necessary to remove secretions by bronchial

suctioning and to administer bronchodilators

and mucolytic agents. If edema of the airway develops, endotracheal intuba-tion

may be necessary. Continuous positive airway pressure and mechanical

ventilation may also be required to achieve adequate oxygenation.

After adequate respiratory status and circulatory

status have been established, the patient is assessed for cervical spinal

injuries or head injury if the patient was involved in an explosion, a fall, a

jump, or an electrical injury. Once the patient’s condition is sta-ble,

attention is directed to the burn wound itself. All clothing and jewelry are

removed. For chemical burns, flushing of the ex-posed areas is continued. The

patient is checked for contact lenses. These are removed immediately if

chemicals have contacted the eyes or if facial burns have occurred.

It

is important to validate an account of the burn scenario pro-vided by the

patient, witnesses at the scene, and paramedics. In-formation needs to include

time of the burn injury, source of the burn, place where the burn occurred, how

the burn was treated at the scene, and any history of falling with the injury.

A history of preexisting diseases, allergies, and medications and the use of

drugs, alcohol, and tobacco is obtained at this point to plan care. A

large-bore (16- or 18-gauge) intravenous catheter should be in-serted in a

non-burned area (if not inserted earlier). Most patients have a central venous

catheter inserted so that large amounts of intravenous fluids can be given

quickly and central venous pres-sures can be monitored. If the burn exceeds 25%

TBSA or if the patient is nauseated, a nasogastric tube should be inserted and

connected to suction to prevent vomiting due to paralytic ileus (absence of

peristalsis).

The

physician evaluates the patient’s general condition, as-sesses the burn,

determines the priorities of care, and directs the individualized plan of

treatment, which is divided into systemic management and local care of the

burned area. Nonsterile gloves, caps, and gowns are worn by personnel while

assessing the ex-posed burned areas. Clean technique is maintained while

assess-ing burn wounds.

Assessment of both the TBSA burned and the depth of

the burn is completed after soot and debris have been gently cleansed from the

burn wound. Careful attention is paid to keeping the burn patient warm during

wound assessment and cleansing. As-sessment is repeated frequently throughout

burn wound care. Photographs may be taken of the burn areas initially and

period-ically throughout treatment; in this way, the initial injury and burn

wound can be documented. Such documentation is invalu-able for insurance and

legal claims. Clean sheets are placed under and over the patient to protect the

area from contamination, maintain body temperature, and reduce pain caused by

air cur-rents passing over exposed nerve endings.

An

indwelling urinary catheter is inserted to permit more ac-curate monitoring of

urine output and renal function for patients with moderate to severe burns.

Baseline height, weight, arterial blood gases, hematocrit, electrolyte values,

blood alcohol level, drug panel, urinalysis, and chest x-rays are obtained. If

the patient is elderly or has an electrical burn, a baseline electrocardiogram

is obtained. Because burns are contaminated wounds, tetanus pro-phylaxis is

administered if the patient’s immunization status is not current or is unknown.

Although the major focus of care during the

emergent phase is physical stabilization, the nurse must also attend to the

patient’s and family’s psychological needs. Burn injury is a crisis, causing

variable emotional responses. The patient’s and family’s coping abilities and

available supports are assessed. Circumstances sur-rounding the burn injury

should be considered when providing care. Individualized psychosocial support

must be given to the pa-tient and family. Because the emergent burn patient is

usually anxious and in pain, those in attendance should provide reassur-ance

and support, explanations of procedures, and adequate pain relief. Because poor

tissue perfusion accompanies burn injuries, only intravenous pain medication

(usually morphine) is given, titrated for the patient. If the patient wishes to

see a spiritual advisor, one is notified.

TRANSFER TO A BURN CENTER

The

depth and extent of the burn are considered in determin-ing whether the patient

should be transferred to a burn center. Patients with major burns, those who

are at the extremes of the age continuum, those with coexisting health problems

that may affect recovery, and those with circumstances that increase their risk

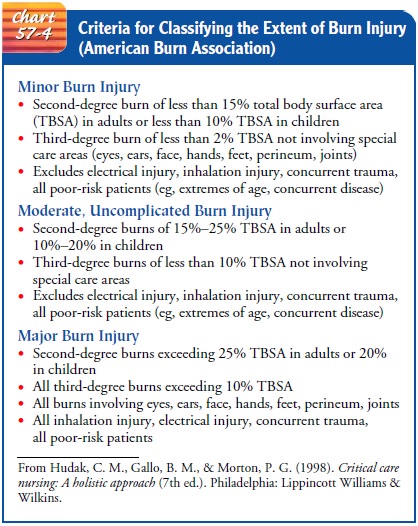

for acute and long-term complications are transferred to a burn center. Chart

57-4 lists the American Burn Associa-tion’s criteria for burn center referral

after initial assessment and management.

If

the patient is to be transported to a burn center, the follow-ing measures are

instituted before transfer:

·

A secure intravenous catheter

is inserted with lactated Ringer’s solution infusing at the rate required to

maintain a urine output of at least 30 mL per hour.

·

A patent airway is ensured.

·

Adequate pain relief is

attained.

·

Adequate peripheral

circulation is established in any burned extremity.

·

Wounds are covered with a

clean, dry sheet, and the patient is kept comfortably warm.

All assessments and treatments are documented, and this in-formation is provided to the burn center personnel. The trans-ferring facility must relay accurate intake and output totals to burn center personnel so that adequate fluid resuscitation mea-sures continue.

MANAGEMENT OF FLUID LOSS AND SHOCK

Next

to handling respiratory difficulties, the most urgent need is preventing

irreversible shock by replacing lost fluids and electro-lytes. As mentioned

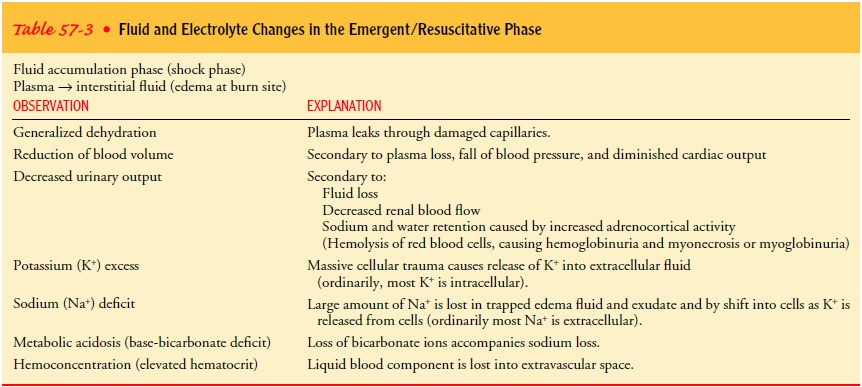

previously, survival of burn victims depends on adequate fluid resuscitation. Table

57-3 summarizes the fluid and electrolyte changes in the emergent phase of burn

care. Intra-venous lines and an indwelling catheter must be in place before

implementing fluid resuscitation. Baseline weight and laboratory test results

are obtained as well. These parameters must be mon-itored closely in the

immediate post-burn (resuscitation) period. Controversy continues regarding the

definition of adequate re-suscitation and the optimal fluid type for

resuscitation. Refine-ment of resuscitation techniques remains an active area

of burn research.

Fluid Replacement Therapy.

The total volume and rate of intra-venous fluid

replacement are gauged by the patient’s response. The adequacy of fluid

resuscitation is determined by following urine output totals, an index of renal

perfusion. Output totals of 30 to 50 mL/hour have been used as goals. Other

indicators of adequate fluid replacement are a systolic blood pressure

exceed-ing 100 mm Hg and/or a pulse rate less than 110/minute.

Additional gauges of fluid requirements and

response to fluid resuscitation include hematocrit and hemoglobin and serum

sodium levels. If the hematocrit and the hemoglobin levels de-crease or if the

urinary output exceeds 50 mL/hour, the rate of intravenous fluid administration

may be decreased. The goal is to maintain serum sodium levels in the normal

range during fluid replacement.

Appropriate resuscitation endpoints for burn

patients remain controversial. Research in this area has led to the study of

hemo-dynamic and oxygen transport resuscitation endpoints. When these endpoints

were used, massive fluid resuscitation volumes were administered that could

have deleterious effects. Successful resuscitation is associated with increased

delivery of oxygen and consumption of oxygen with declining serum lactate

levels (Holm et al., 2000). Attention has been directed recently toward other

indicators of adequate resuscitation: base deficit and serum lac-tate levels.

Measurement of serum lactate levels does not appear useful in the treatment of

burn patients because of the large amounts of lactate released from burned

tissue; however, metab-olism of lactate is unaltered. Elevated levels occur

despite ade-quate fluid resuscitation (Yowler & Fratianne, 2000). Factors

that are associated with the increased fluid requirements include delayed

resuscitation, scald burn injuries, inhalation injuries, high-voltage

electrical injuries, hyperglycemia, alcohol intoxica-tion, and chronic diuretic

therapy. Second 24-hour post-burn fluid infusion rates incorporate both the

maintenance amount of fluid and any additional fluid needs secondary to

evaporative water loss through the burn wound.

Fluid Requirements.

The projected fluid requirements for the first 24 hours are calculated by the clinician based on the extent of the burn injury. Some combination of fluid categories may be used: colloids (whole blood, plasma, and plasma expanders) and crystalloids/electrolytes (physiologic sodium chloride or lactated Ringer’s solution).

Adequate fluid resuscitation results in slightly decreased blood

volume levels during the first 24 post-burn hours and restores plasma levels to

normal by the end of 48 hours. Oral resuscitation can be successful in adults

with less than 20% TBSA and children with less than 10% to 15% TBSA.

Formulas have been developed for estimating fluid

loss based on the estimated percentage of burned TBSA and the weight of the

patient. Length of time since burn injury occurred is also very important in

calculating estimated fluid needs. Formulas must be adjusted so that initiation

of fluid replacement reflects the time of injury. Resuscitation formulas are

approximations only and are in-dividualized to meet the requirements of each

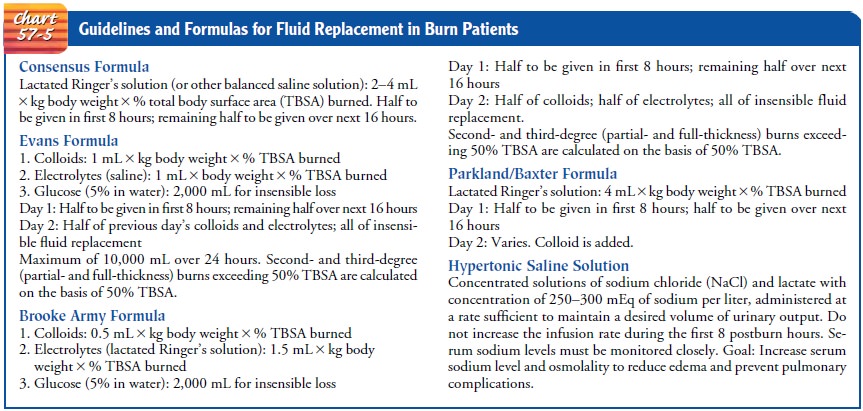

patient. The vari-ous formulas are discussed below and summarized in Chart

57-5.

As early as 1978, the NIH Consensus Development Confer-ence on Supportive Therapy in Burn Care established that salt and water are required in burn patients, but that colloid may or may not be useful during the first 24 to 48 post-burn hours. The con-sensus formula provides for the volume of balanced salt solution to be administered in the first 24 hours in a range of 2 to 4 mL/kg per percent burn. In general, 2 mL/kg per percent burn of lactated Ringer’s solution may be used initially for adults. This is the most common fluid replacement formula in use today. As with the other formulas, half of the calculated total should be given over the first 8 post-burn hours, and the other half should be given over the next 16 hours. The rate and volume of the infusion must be regulated according to the patient’s response by changing the hourly infusion rates. Fluid boluses are recommended only in the presence of marked hypotension, not low urine output. Typical fluid rate changes should involve an increase or decrease in flow rate by no more than 25% to 33% (Yowler & Fratianne, 2000).

Studies demonstrate that with large burns, there is

a failure of the sodium-potassium pump (a physiologic mechanism involved in

fluid–electrolyte balance) at the cellular level. Thus, patients with very

large burns may need proportionately more milliliters of fluid per percent of

burn than those with smaller burns. Also, patients with electrical injury,

pulmonary injury, and delayed fluid resuscitation and those who were burned

while intoxicated may need additional fluids.

The

following example illustrates use of the formula in a 70-kg (168-lb) patient

with a 50% TBSA burn:

·

Consensus formula: 2 to 4

mL/kg/% TBSA

·

2 × 70 × 50 = 7,000 mL/24 hours

·

Plan to administer: First 8

hours = 3,500 mL, or 437 mL/

hour; next 16 hours =

3,500 mL, or 219 mL/hour

Most

fluid replacement formulas use isotonic electrolyte solu-tions. Regardless of

which standard replacement formula is used, the patient receives approximately

the same fluid volume and sodium replacement during the first 48 hours.

Another fluid replacement method requires

hypertonic elec-trolyte solutions. This method uses concentrated solutions of

sodium chloride and lactate (a balanced salt solution) so that the resulting

fluid has a concentration of 250 to 300 mEq of sodium. The rationale for this

replacement method is that by increasing serum osmolality, fluid will be pulled

back into the vascular space from the interstitial space. Reduced systemic and

pulmonary edema has been reported after administering hypertonic solutions.

Gerontologic Considerations

Decreased

function of the cardiovascular, renal, and pulmonary systems increases the need

for close observation of elderly patients with even relatively minor burns

during the emergent and acute phases. Acute renal failure is much more common

in elderly pa-tients than in those younger than age 40. The margin of

difference between hypovolemia and fluid overload is very small. Suppressed

immunologic response, a high incidence of malnutrition, and an inability to

withstand metabolic stressors (eg, a cold environ-ment) further compromise the

elderly person’s ability to heal. As a result of these issues in elderly

patients who sustain burn injury, close monitoring and prompt treatment of

complications are mandatory.

Nursing Management:Emergent/Resuscitative Phase

Assessment data obtained by prehospital providers

(rescuers such as emergency medical technicians) are shared with the physician

and nurse in the emergency department. Nursing assessment in the emergent phase

of burn injury focuses on the major priorities for any trauma patient; the burn

wound is a secondary consideration. Aseptic management of

the burn wounds and invasive lines continues.

The nurse monitors vital signs frequently.

Respiratory status is monitored closely, and apical, carotid, and femoral

pulses are eval-uated. Cardiac monitoring is indicated if the patient has a

history of cardiac disease, electrical injury, or respiratory problems, or if

the pulse is dysrhythmic or the rate is abnormally slow or rapid.

If all extremities are burned, determining blood

pressure may be difficult. A sterile dressing applied under the blood pressure

cuff will protect the wound from contamination. Because increas-ing edema makes

blood pressure difficult to auscultate, a Doppler (ultrasound) device or a

noninvasive electronic blood pressure de-vice may be helpful. In severe burns,

an arterial catheter is used for blood pressure measurement and for collecting

blood speci-mens. Peripheral pulses of burned extremities are checked hourly;

the Doppler device is useful for this. Elevation of burned extremi-ties is

crucial to decrease edema. Elevation of the lower extremities on pillows and of

the upper extremities on pillows or by suspen-sion using intravenous poles may

be helpful.

Large-bore intravenous catheters and an indwelling

urinary catheter are inserted, and the nurse’s assessment includes monitor-ing

fluid intake and output. Urine output, an indicator of renal per-fusion, is

monitored carefully and measured hourly. The amount of urine first obtained

when the urinary catheter was inserted is recorded. This may assist in

determining the extent of preburn renal function and fluid status. Urine

specific gravity, pH, and glucose, acetone, protein, and hemoglobin levels are

assessed frequently.

Burgundy-colored

urine suggests the presence of hemochro-mogen and myoglobin resulting from

muscle damage. This is as-sociated with deep burns caused by electrical injury

or prolonged contact with flames. Glucosuria, a common finding in the early

postburn hours, results from the release of stored glucose from the liver in

response to stress.

Although

not responsible for calculating the patient’s fluid requirements, the nurse

needs to know the maximum volume of fluid the patient should receive. Infusion

pumps and rate con-trollers are used to deliver a complex regimen of prescribed

intra-venous fluids. Administering and monitoring intravenous therapy are major

nursing responsibilities.

Body temperature, body weight, preburn weight, and

history of allergies, tetanus immunization, past medical and surgical

prob-lems, current illnesses, and use of medications are assessed. A

head-to-toe assessment is performed, focusing on signs and symptoms of

concomitant illness, injury, or developing complications. Pa-tients with facial

burns should have their eyes examined for po-tential injury to the corneas. An

ophthalmologist is consulted for complete assessment via fluorescent staining.

Assessing the extent of the burn wound continues

and is facili-tated with anatomic diagrams (described previously). In addition,

the nurse works with the physician to assess the depth of the wound and areas

of full- and partial-thickness injury. Assessment of the circumstances

surrounding the injury is important. Ob-taining a history of the burn injury

can help to plan the care for the patient. Assessment should include the time

of injury, mechanism of burn, whether the burn occurred in a closed space, the

possibil-ity of inhalation of noxious chemicals, and any related trauma.

The

neurologic assessment focuses on the patient’s level of consciousness,

psychological status, pain and anxiety levels, and behavior. The patient’s and

family’s understanding of the injury and treatment is assessed as well.

Nursing care of the patient during the emergent/resuscitative phase of burn injury is detailed in the Plan of Nursing Care.

Related Topics