Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Applied physiology and pharmacology : A brief pharmacology related to anesthesia

Drugs to raise blood pressure

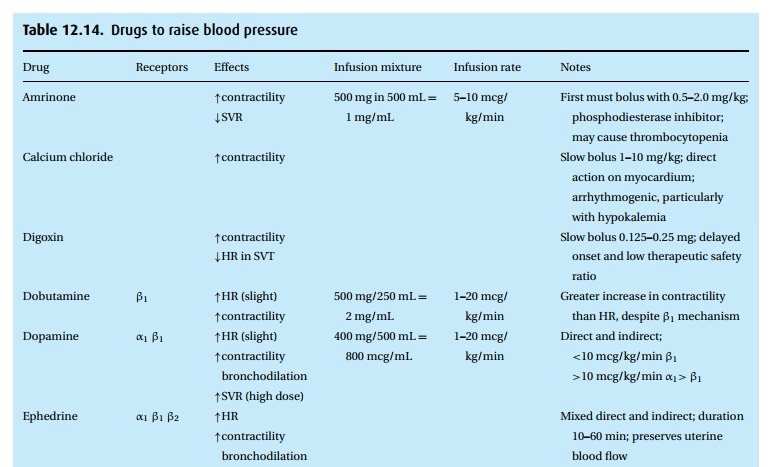

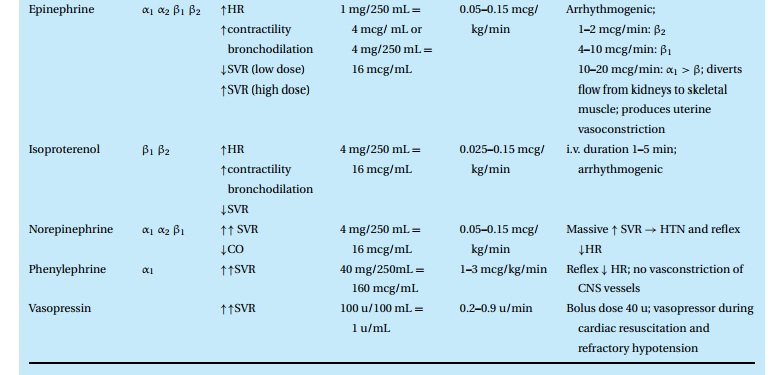

Drugs to raise blood pressure

(Table 12.14)

Hypotension

is initially treated with intravenous fluids, lightening of anesthesia, and

asking the surgeon not to compress major vessels such as the vena cava (if that

was responsible for reducing preload). Sometimes elevating the legs and thereby

increasing venous return can help to improve cardiac output and arterial blood

pressure. In addition, several drugs are available to improve myocardial

con-tractility, increase arterial resistance, and decrease venous capacitance

through adrenergic effects (Table 12.14).

Ephedrine

The old standby still finds common use. We rely on its three-armed effects, alpha and beta stimulation as well as a release of norepinephrine from postganglionic sympathetic nerve terminals. Ten to 20 mg intravenously will increase heart rate and arterial pressure and stimulate the CNS, which we usually do not observe when we give the drug during anesthesia. It has a duration of action of about 20 minutes.

Epinephrine/norepinephrine

Epinephrine

(adrenalin in Britain) and norepinephrine (and noradrenalin) are the two

catecholamines we find circulating in blood. Norepinephrine is liberated from

sympathetic nerve terminals and the adrenal medulla, while epinephrine comes

only from the adrenal gland. Chemically, these two transmitter substances are

identical but for a methyl group on the amine gracing epinephrine but not norepinephrine (NOR=N Ohne (German for “without”) Radical). The drugs dowhat

sympathetic stimulation does. Being physiologic transmitter substances, these

catecholamines have a fleeting effect. Single bolus injections last only for a

matter of a few minutes.

The body

makes extensive use of these catecholamines when fight, fright, or flight call

for cardiovascular, pulmonary, muscular, ocular, and intestinal adjust-ments.

It is amazing how well these substances with overlapping adrenergic effects

orchestrate their actions to an optimal end-result of sympathetic stimulation.

Clinically, we are limited to giving one drug or the other, counting on just

one or the other effect. For example, low doses of epinephrine may reduce blood

pressure a little through a beta2 effect, while larger doses raise

pressure and accelerate heart rate. With norepinephrine, we see primarily

increased pressure without tachycar-dia – as long as the baroreceptors are

active. Typical doses used in the operating room might start with 10 to 20 mcg

of epinephrine as a single i.v. bolus to help the average adult patient through

a spell of hypotension, for example during ana-phylaxis. Usually reserved for

more dire situations, we titrate a norepinephrine infusion to effect, starting

perhaps with 0.1 mcg/kg/min. Epinephrine can also be given by continuous

infusion. During cardiac resuscitation when we assume the body to have become

very much less responsive to circulating catecholamines, doses as high as 1 mg

epinephrine as a bolus have been used.

Dopamine

A

biochemical forerunner to norepinephrine, dopamine also finds clinical use. It

has the – undeserved – aura that in low rates of infusion, e.g., 1–3

mcg/kg/min, it can support blood pressure while maintaining renal perfusion and

promoting diuresis. In larger concentrations, it turns into a vasopressor with

renal vaso-constriction, just as norepinephrine, which it can liberate from

post-ganglionic sympathetic terminals.

Dobutamine (Dobutrex®)

A synthetic catecholamine, dobutamine is a selective β1 agonist with greater effect on contractility than heart rate. It improves cardiac output in patients in cardiac failure. Because of its rapid metabolism, we administer dobutamine as an infusion at 2 to 10 mcg/kg/min, titrated to effect.

Isoproterenol (Isuprel®)

Another

synthetic catecholamine, isoproterenol activates both β1 and β2

recep-tors with great vigor (2–10 times the potency of epinephrine). We use

this agent to (i) increase heart rate, (ii) decrease pulmonary vascular

resistance, andrarely, bronchodilate (i.v. or as an aerosol). Typical of β1

agonism, heart rate, contractility and cardiac output increase while β2

vasodilation reduces SVR. The net effect is a fall in diastolic and mean blood

pressures. Isoproterenol also induces arrhythmias.

Phenylephrine (Neosynephrine®)

An old

standby, phenylephrine sees vasoconstrictive service in nose drops and as an

intravenous, pure α1 agonist. We expect to see both venous and

arterial vasoconstriction with the typical intravenous bolus of 40 to 100 mcg,

which should raise blood pressure for about 5 minutes. Because of its

relatively short duration of effect, we can also infuse it at a rate of about

10 to 100 mcg/min (titrated to effect). Lacking effects at the β receptors, the

drug will not increase heart rate or contractile force. Instead, a baroreceptor

response can lead to lower heart rates.

Related Topics