Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Genitourinary system

Dialysis - Investigations and procedures

Dialysis

When the kidneys fail to a degree that causes symptoms and complications of renal failure, renal replacement therapy (RRT) is needed to remove waste products and fluid, and to restore electrolytes and fluid balance to as normal as possible. There are several types of RRT, including haemodialysis, haemofiltration and peritoneal dialysis. Despite advances in technology, these are still unable to completely mimic renal function, and none are able to replace the endocrine functions of the kidney.

Renal transplantation is a special form of RRT which most closely restores a physiological state, including the endocrine functions. Patients may switch modality many times whilst on RRT.

Haemodialysis

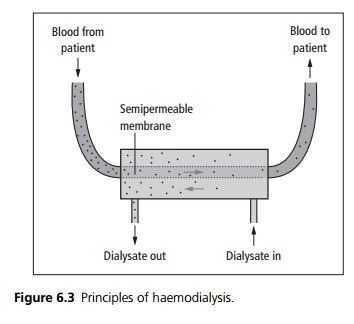

Blood has to be pumped from the patient, and passed through a ŌĆśdialyserŌĆÖ, sometimes called an artificial kidney. The dialyser consists of an array of semi-permeable membranes. The blood flows past the membrane on one side, whilst on the other side, a solution of purified wa-ter, sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, dextrose and bicarbonate or acetate is kept flowing in the other direction (counter-current ŌĆō see Fig. 6.3).

Solutes diffuse across the semi-permeable membrane down a concentration gradient. Small solutes with a large concentration gradient diffuse rapidly, e.g. urea and cre-atinine, whereas diffusion is slower with larger molecules or if the concentration gradient is low.

The diffusion gradient is kept high by keeping blood and dialysate flows high, and also by using counter-current flow. Proteins are too large to cross the mem-brane. fluid is removed by generating a transmembrane pressure, so that fluid is pushed out from the blood compartment into the dialysate compartment. Water drags small and medium molecular weight solutes with it. This is called ultrafiltration. Several hours of dialysis, usually three times a week, are needed to achieve satisfactory urea and creatinine clearance. Underdialysis (lack of adequate dialysis) is associated with an increase in cardiovascular and other morbidity and mortality. To remove and return blood, the patient must have vascular access such as an arteriovenous fistula or a doublelumen central venous line. The blood needs to be anticoagulated (usually with heparin) to stop it clotting in the dialysis machine.

Although many patients cope very well with dialysis, common symptoms include headache, joint pains and fatigue during and after a dialysis session. Complications include hypotension, line infections, dialysis amyloid and increased cardiovascular mortality.

Haemofiltration

Continuous renal replacement therapy, as takes place on intensive care units, uses ultrafiltration as the main method rather than dialysis. Convection carries water and solutes across a highly permeable membrane and this is removed. Before the blood is returned to the body, fluid is replaced using a lactate or bicarbonate-based solution containing solutes in the desired concentrations (see Fig. 6.4).

The advantage of continuous therapy is that removal of fluid and changes in electrolyte concentration take place more gradually, reducing this risk of hypotension. It is expensive in both materials and staffing and therefore only takes place on intensive care units.

Peritoneal dialysis

In peritoneal dialysis (PD), fluid and solutes are exchanged across the peritoneal membrane by putting dialysis solution into the abdominal cavity. Peritoneal access is obtained by putting a tube through the anterior abdominal wall. Dialysate is run under gravity into the peritoneal cavity and the fluid is left there for several hours. Small solutes diffuse down their concentration gradients between capillary blood vessels in the peritoneal lining and the dialysate. Fluid removal takes place by osmosis. The osmotically active agent in PD fluid is usually dextrose.

Dialysate exchanges are usually performed by the patient, four or five times a day (CAPD ŌĆō continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis), or some or all of the exchanges can by performed by an automated cycling device to which the patient is attached at night (APD ŌĆō automated peritoneal dialysis). Patients often develop some constipation which can limit the flow of dialysate, they are treated with laxatives. Hernias should be repaired before starting PD.

Bacterial infection of the tunnelled catheter and bacterial peritonitis are the most common serious complications. Patients with PD peritonitis present with abdominal pain (80%), ŌĆścloudy bagsŌĆÖ, fever and nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea without classical signs of peritonitis. This can be treated by adding antibiotics to the peritoneal dialysate. In the longer term, PD may become unable to adequately dialyse a patient, as the peritoneal membrane fails.

Related Topics