Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Genitourinary system

Chronic renal failure - Disorders of the kidney

Chronic renal failure

Definition

Chronic renal failure (CRF) is a loss of renal function occurring over months to years because of the destruction of nephrons. End-stage renal failure (ESRF) is loss of renal function requiring any form of chronic renal replacement therapy, i.e. long-term dialysis or transplan-breaktation.

Incidence

The exact number of people with chronic renal failure is difficult to estimate, as many are undetected. The number who progress to endstage renal failure and commence renal replacement therapy is Ōł╝100 per million population per year in the U.K.

Aetiology

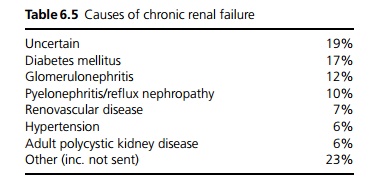

The main causes in England and Wales (2002) are listed in Table 6.5. Certain systemic diseases commonly cause renal disease such as amyloid, myeloma, systemic lupus erythematosus and gout.

In a significant proportion of patients no underlying cause is found. These patients are often labelled as ESRF secondary to hypertension, but this may be a result of the renal failure rather than the cause.

Pathophysiology

Progressive destruction of nephrons leads to gradual reduction in renal function, with loss of the three functions of the kidney:

1. Electrolyte and water homeostatic disturbance may cause fluid overload, hypertension, hyperkalaemia and metabolic acidosis as well as rises in serum urea and creatinine. Initially there may be a phase of large volumes of dilute urine production due to reduction in tubular reabsorption. As the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) falls further urine volumes fall to less than normal.

2. Excretion of waste products, drugs and toxins is reduced leading to complications of toxicity.

3. The hormone functions of the kidney are also affected: reduction of vitamin D activation causes hypocalcaemia and hyperparathyroidism; reduced erythropoietin production causes anaemia.

As renal function declines to about 10ŌĆō20% of normal, i.e. a GFR of Ōł╝15 mL/min, symptoms develop. Acute renal failure (ARF) may also lead to these symptoms, although they are more commonly seen in CRF. This is called uraemia ŌĆō which literally means ŌĆśurine in the bloodŌĆÖ. The onset of uraemia is insidious, but by the time serum urea is >40 mmol/L, creatinine >1000 ┬Ąmol/L, most patients have symptoms. No single toxin has been identified, and in fact urea itself is not thought to be very toxic, but it acts as a convenient marker for other products.

Clinical features

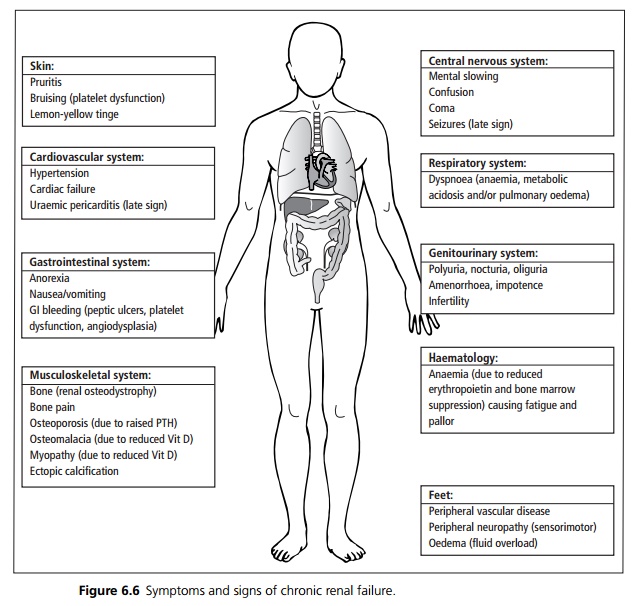

The onset of symptoms is variable. Early symptoms are mostly due to anaemia (malaise, fatigue and shortness of breath on exertion). Late symptoms include pruritis, anorexia, nausea and vomiting ŌĆō very late symptoms are pericarditis, encephalopathy (confusion, coma, seizures) and tachypnoea due to metabolic acidosis.

There are few signs of ESRF, although there may be signs of the underlying cause such as diabetic retinopathy, renal or femoral bruits, an enlarged prostate or polycystic kidneys. It is important to assess the fluid status by looking at the jugular venous pressure, skin turgor, lying and standing blood pressure, and for evidence of pulmonary or peripheral oedema (see Fig. 6.6).

Complications

CRF patients are much more prone to ARF (acute-on-chronic renal failure), for example due to drugs, radiographic contrast and dehydration. Patients with CRF are affected by accelerated atherosclerosis which occurs due to long-term hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, disordered calcium and phosphate metabolism (calcified vessels) and uraemia. They also develop left ventricular hypertrophy due to hypertension. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are much higher than in patients with normal renal function.

Macroscopy/microscopy

The kidneys are usually small and shrivelled, with scarring of glomeruli, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy.

Investigations

The aim of investigations is to make a diagnosis of the cause, and in addition, to consider if there is any acute condition precipitating the renal failure, e.g. prerenal failure, sepsis, obstruction or a nephrotoxin. Any previous historical urea and creatinine measurements are very useful.

The investigations for ARF on CRF or undiagnosed CRF are similar to those for ARF, including the blood tests, imaging and possibly renal biopsy.

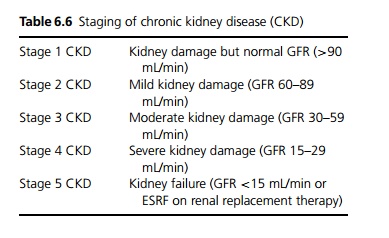

Chronic renal failure is now classified as stages 1ŌĆō5 of chronic kidney disease, according to GFR and other features (see Table 6.6).

In the routine follow-up of CRF, the usual investigations include the following:

┬Ę FBC to look for anaemia.

┬Ę U&E to assess progress of the renal failure, ensure Na+ and K+ are normal.

┬Ę Bicarbonate to look for acidosis.

┬Ę Calcium, phosphate, ALP, PTH (X-ray hands to assess for renal osteodystrophy).

┬Ę CRP (ESR is normally raised in CRF, but a raised CRP suggests infection).

┬Ę Hyperlipidaemia should be looked for.

┬Ę Urinalysis is performed to look for proteinuria and haematuria (if new or increasing these may need further investigation) and urinary tract infections.

┬Ę Underlying causes may need to be monitored, e.g. HbA1C for diabetes mellitus and urate for gout.

Management

The aim is to delay the onset of end-stage renal failure (ESRF) and uraemia as long as possible. Refer early to a renal specialist (certainly if the serum creatinine is Ōēź150 ┬Ąmol/L).

┬Ę Identify and treat any underlying causes appropriately such as glomerulonephritis, diabetes, hypertension, obstruction, recurrent urinary tract infections. Proteinuria may be reduced by ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists.

┬Ę Diet: Salt restriction if hypertensive, potassium restrict if hyperkalaemia is a problem, ensure adequate calories and a reasonable protein intake, supplement vitamins and iron. Patients need to follow a low phosphate diet.

┬Ę Avoid nephrotoxic agents if possible, and review and adjust drug doses.

┬Ę Cardiovascular: Treat even mild hypertension and consider treating hyperlipidaemia. Encourage patients to stop smoking and take regular exercise. Oedema may respond to fluid restriction and/or diuretics.

┬Ę Early symptoms due to anaemia are often treated effectively by giving erythropoietin.

┬Ę Bone disease needs to be treated, with calcium and vitamin D (alfacalcidol) supplements, but aim to lower serum phosphate with reduced intake and phosphate binders.

Some patients will live out their life with the above treatments, and die of other causes. Others may not be fit for dialysis, or prefer conservative treatment. Dialysis is indicated when symptoms of uraemia develop, but before problems with fluid overload, hyperkalaemia or late-stage symptoms such as pericarditis ensue.

Prognosis

Treatment ameliorates some of the symptoms and biochemical disturbances; however, not all patients respond to treatment. Renal transplantation offers the best treatment, but is of limited availability.

Related Topics