Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Vulvar and Vaginal Disease and Neoplasia

Benign Vulvar Disease

BENIGN VULVAR DISEASE

In the past, the classification

of benign, noninfectious vulvar disease used descriptive terminology based on

gross clinical morphologic appearance such as leukoplakia, kraurosis vulvae,

and hyperplastic vulvitis. Currently, these diseases are classified into three

categories: squamous cell hyperplasia, lichen sclerosus, and other dermatoses.

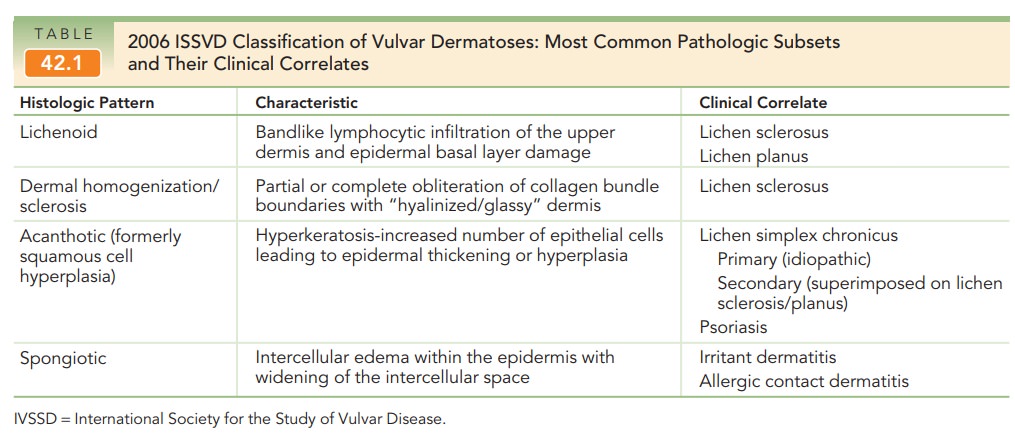

In 2006, the International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease (ISSVD) constructed a new classification using histologic morphology based on consensus among gynecologists, dermatologists, and pathologists involved in the care of women with vulvar disease. Common ISSVD classifications are outlined in Table 42.1.

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen

sclerosus has confused clinicians and pathologistsbecause of

inconsistent terminology and its frequent asso-ciation with other types of

vulvar pathology, including those of the acanthotic variety. As with the other

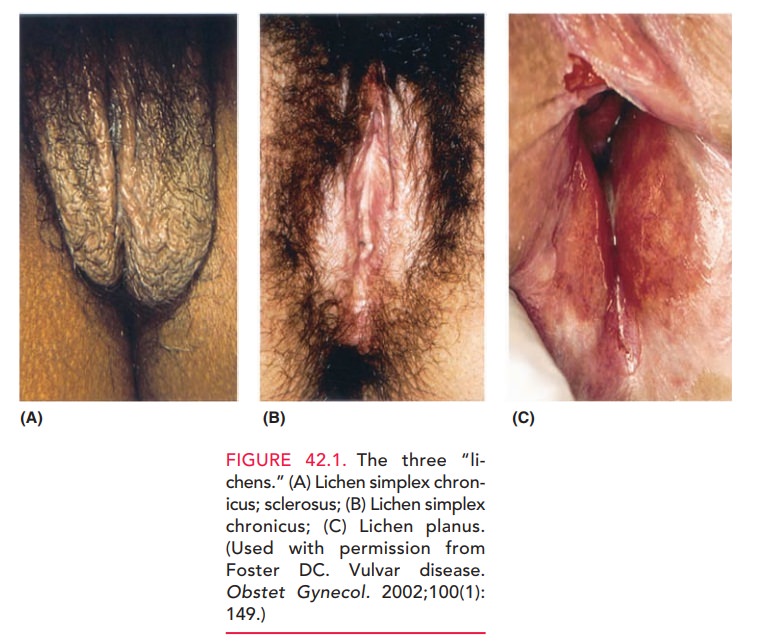

disorders, chronic vulvar pruritus occurs in most patients. Typically,the vulva is diffusely involved,

with very thin, whitish epithe-lial areas, termed “onion skin” epithelium (Fig.

42.1B). Theepithelium has been termed “cigarette paper” skin and described as

“parchment-like.” Most patients have involve-ment on both sides of the vulva,

with the most common sites being the labia majora, labia minora, the clitoral

and periclitoral epithelium, and the perineal body. The lesion may extend to

include a perianal “halo” of atrophic, whitish epithelium, forming a figure-8

configuration with the vul-var changes. In

severe cases, many normal anatomic landmarksare lost, including obliteration of

the labial and periclitoral archi-tecture as well as severe stenosis of the

vaginal introitus. Somepatients have areas of cracked skin, which are prone

to bleeding with minimal trauma. Patients with these severe anatomic changes

complain of difficulty in having normal coital function.

The

etiology of lichen sclerosus is unknown, but a familial association has been

noted, as well as disorders of the immune

However,

the response to topical steroids furtherindicates the underlying inflammatory

process and the role of prostaglandins and leukotrienes in the hallmark symptom

of pruritus. Histologic evaluation and

confirmation of lichen scle-rosis is often necessary and useful, because they

allow specific ther-apy. The histologic features of the lichenoid pattern

includea band of chronic inflammatory cells, consisting mostly of lymphocytes,

in the upper dermis with a zone of homoge-neous, pink-staining, collagenous-like

material beneath the epidermis due to cell death. The obliteration of

boundaries between collagen bundles gives the dermis a “hyalinized” or “glassy”

appearance. This dermal homogenization/ sclerosis pattern is virtually

pathognomonic.

In 27% to 35% of patients, there are associated areas of acanthosis characterized by hyperkeratosis—an increase in the number of epithelial cells (keratinocytes) with flat-tening of the rete pegs.

These areas may be mixed through-out or adjacent to the typically

lichenoid areas. In patients with this mixed pattern, both components need to

be treated to effect resolution of symptoms. Patients in whom a large

acanthotic component has been histologically confirmed should be treated

initially with well-penetrating cortico-steroid creams. With improvement of

these areas (usually 2 to 3 weeks), therapy can then be directed to the

lichenoid component.

Treatment

for lichen sclerosis includes the use of topical steroid (clobetasol)

preparations in an effort to ameliorate symp-toms. The

lesion is unlikely to resolve totally. Intermittenttreatment may be needed

indefinitely, which is in marked contrast to acanthotic lesions, which usually

totally resolve within 6 months.

Lichen

sclerosus does not significantly increase the patient’s risk of developing

cancer.

It has been estimated that this

risk is in the 4% range. However, due to the frequent coexistence with

acanthosis, the condition needs to be followed carefully and a rebiopsy

performed, because therapeutically resistant acanthosis can be a harbinger of

squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

In contrast to many dermatologic

conditions that may be described as “rashes that itch,” lichen simplex

chronicus can be described as “an itch

that rashes.” Most patients develop this disorder secondary to an irritant

dermatitis, which progresses to lichen simplex chronicus as a result of the

effects of chronic mechanical irritation from scratch-ing and rubbing an already

irritated area. The mechanicalirritation

contributes to epidermal thickening or hyperplasia and inflammatory cell

infiltrate, which, in turn, leads to heightened sensitivity that triggers more

mechanical irritation.

Accordingly,

the history of these patients is one of progres-sive vulvar pruritus and/or

burning, which is temporarilyrelieved by scratching or

rubbing with a washcloth or some similar material. Etiologic factors for the

original pruritic symptoms often are unknown, but may include sources of skin

irritation such as laundry detergents, fab-ric softeners, scented hygienic

preparations, and the use of colored or scented toilet tissue. These potential

sources of symptoms must be investigated. Any domestic or hygienic irritants

must be removed, in combination with treatment, to break the cycle described.

On

clinical inspection, the skin of the labia majora, labia minora, and perineal

body often shows diffusely reddened areas with occasional hyperplastic or

hyperpigmented plaques of red to reddish brown (see Fig.

42.1A). One may also find occasionalareas of linear hyperplasia, which show the

effect of grossly hyperkeratotic ridges of epidermis. Biopsy of patients who

have these characteristic findings is usually not warranted.

Empiric treatment to include

antipruritic medications such as diphenhydramine hydrochloride (Benadryl) or

hydroxyzine hydrochloride (Atarax) that inhibit nighttime, unconscious

scratching, combined with a mild to moder-ate topical steroid cream applied to

the vulva, usually pro-vides relief. A steroid cream, such as hydrocortisone

(1% or 2%) or, for patients with significant areas of obvious hyperkeratosis,

triamcinolone acetonide or betamethasone valerate may be used. If significant relief is not obtained

within3 months, diagnostic vulvar biopsy is warranted.

The

prognosis for this disorder is excellent when the offend-ing irritating agents

are removed and a topical steroid prepara-tion is used appropriately. In most

patients, these measurescure the problem and eliminate future recurrences.

Lichen Planus

Although lichen planus is usually a desquamative lesion of the vagina,

occasional patients develop lesions on the vulva near the inner aspects of the

labia minora and vulvar vestibule. Patients may have areas of whitish, lacy

bands (Wickham striae) of keratosis near the reddish ulcerated-like lesions

characteristic of the disease (see Figure 42.1C). Typically, complaints include chronic vulvar burning and/or pruritus

and insertional (i.e., entrance) dyspareunia and a pro-fuse vaginal discharge. Because

of the patchiness of thislesion and the concern raised by atypical appearance

of the lesions, biopsy may be warranted to confirm the diagnosis in some

patients. In lichen planus, biopsy shows no atypia. Examination of the vaginal

discharge in these patients fre-quently reveals large numbers of acute

inflammatory cells without significant numbers of bacteria. Accordingly, the

diagnosis most often can be made by the typical history of vaginal/vulvar

burning and/or insertional dyspareunia, coupled with a physical examination

that shows the bright red patchy distribution; and a wet prep that shows large

numbers of white cells. Histologically the epithelium is thinned, and there is

a loss of the rete ridges with a lym-phocytic infiltrate just beneath,

associated with basal cell liquefaction necrosis.

Treatment for lichen planus is

topical steroid prepa-rations similar to those used for lichen simplex

chronicus. This may include the use of intravaginal 1% hydrocorti-sone douches.

Length of treatment for these patients is often shorter than that required to

treat lichen simplex chronicus, although lichen planus is more likely to recur.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an autosomal dominant

inherited disorder that caninvolve the vulvar skin as part of a generalized

dermatologic process. With approximately 2% of the

general populationsuffering from psoriasis, the physician should be alert to

its prevalence and the likelihood of vulvar manifestation, because it may

appear during menarche, pregnancy, and menopause.

The lesions are typically

slightly raised round or ovoid patches with a silver scale appearance atop an

erythema-tous base. These lesions most often measure approximately 1 × 1 to 1 × 2 cm. Though pruritus is usually

minimal, these silvery lesions will reveal punctate bleeding areas if removed

(Auspitz sign). The diagnosis is

generally known because ofpsoriasis found elsewhere on the body, obviating the

need for vul-var biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Histologically, a

prominentacanthotic pattern is seen,

with distinct dermal papillaethat are clubbed and chronic inflammatory cells

between them.

Treatment often occurs in

conjunction with consulta-tion by a dermatologist. Like lesions elsewhere,

vulvar lesions usually respond to topical coal tar preparations, followed by

exposure to ultraviolet light as well as cortico-steroid medications, either

topically or by intralesional injection. Coal tar preparations are extremely

irritating to the vagina and labial mucous membranes and should not be used in

these areas. Because vulvar application

of some of thephotoactivated preparations can be somewhat awkward, topical

steroids are most effective, using compounds such as betametha-sone valerate

0.1%.

Dermatitis

Vulvar

dermatitis falls into two main categories: eczema and seborrheic

dermatitis. Eczema can be further sub-divided into exogenous and endogenous

forms. Irritant and allergic contact

dermatitis are forms of exogenous eczema. They are usually reactions to

potential irritants or allergens found in soaps, laundry detergents, textiles,

and feminine hygiene products. Careful history can be helpful in identifying

the offending agent and in preventing recur-rences. Atopic dermatitis is a form of endogenous eczema that often affects

multiple sites, including the flexural sur-faces of the elbows and knees,

retroauricular area, and scalp. The lesions associated with these three forms

of dermatitis can appear similar: symmetric eczematous lesions, with underlying

erythema. Histology alone will not distinguish these three types of dermatitis.

They all exhibit a spongi-otic pattern characterized

by intercellular edema withinthe epidermis, causing widening of the space

between the cells. Therefore, these entities must often be distinguished

clinically.

Although seborrheic dermatitis is a common

problem, iso-lated vulvar seborrheic dermatitis is rare. It

involves a chronicinflammation of the sebaceous glands, but the exact cause is

unknown. The diagnosis is usually made in patients com-plaining of vulvar pruritus

who are known to have sebor-rheic dermatitis in the scalp or other hair-bearing

areas of the body. The lesion may mimic other entities such as pso-riasis or

lichen simplex chronicus. The lesions are

pale red toa yellowish pink and may be covered by an oily appearing, scaly

crust. Because this area of the body remains continuallymoist, occasional

exudative lesions include raw “weeping” patches, caused by skin maceration,

which are exacerbated by the patient’s scratching. As with psoriasis, vulvar biopsy isusually not needed when the

diagnosis is made in conjunction with known seborrheic dermatitis in other

hair-bearing areas. Thehistologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are a

combina-tion of those seen in the acanthotic and spongiotic patterns.

Treatment for vulvar dermatitis

involves removing the offending agent, if applicable, initial perineal hygiene

and the use of a 5% solution of aluminum acetate several times a day, followed

by drying. Topical corticosteroid lotions or creams containing a mixture of an

agent that penetrates well, such as betamethasone valerate, in conjunction with

crotamiton, can be used for symptom control. As with LSC, the use of

antipruritic agents as a bedtime dose in the first 10 days to 2 weeks of

treatment frequently helps break the sleep/scratch cycle and allows the lesions

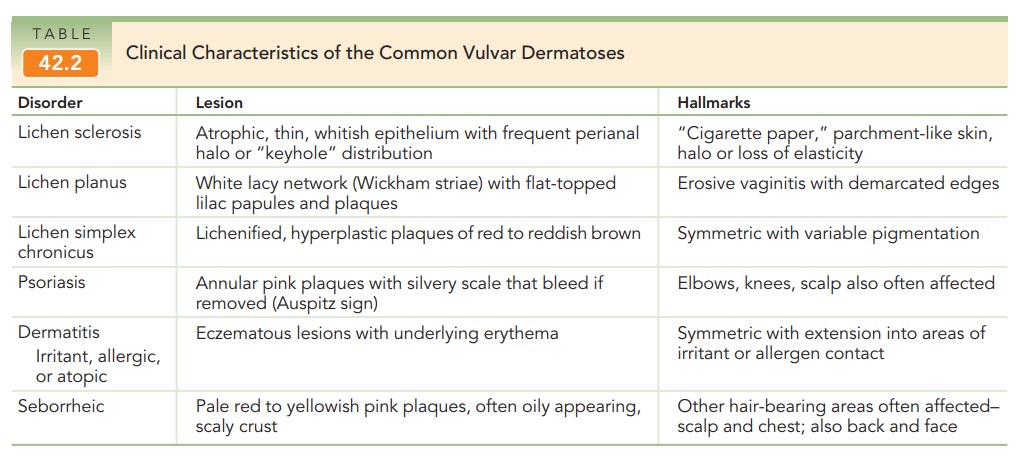

to heal. Table 42.2 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the common

vul-var dermatoses.

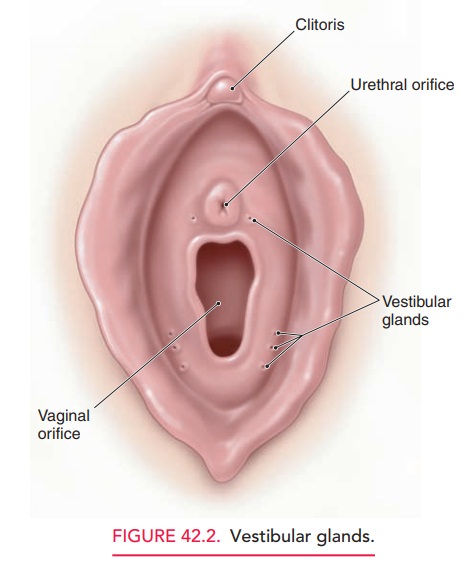

Vestibulitis

Vulvar vestibulitis is a condition of unknown etiology. Itinvolves the acute and chronic inflammation of the vestibu-lar glands, which lie just inside the vaginal introitus near the hymeneal ring. The involved glands may be circumferential to include areas near the urethra, but this condition most commonly involves posterolateral vestibular glands between the 4 and 8 o’clock positions (Fig. 42.2). The diagnosis shouldbe suspected in all patients who present with new onset insertional dyspareunia. Patients with this condition frequently com-plain of progressive insertional dyspareunia to the point where they are unable to have intercourse. The history may go on for a few weeks, but most typically involves progres sive worsening over the course of 3 or 4 months. Patients also complain of pain on tampon insertion and at times dur-ing washing or bathing the perineal area.

Physical examination is the key

to diagnosis. Because the vestibular glands lie between the folds of the

hymenal ring and the medial aspect of the vulvar vestibule, diagno-sis is

frequently missed when inspection of the perineum does not include these areas:

Once the speculum has been placedin the

vagina, the vestibular gland area becomes impossible to identify. After

carefully inspecting the proper anatomic area,a light touch with a moistened

cotton applicator recreates the pain exactly and allows for quantification of

the pain. In addition, the regions affected are most often evident as small,

reddened, patchy areas.

Because the cause of vestibulitis

is unknown, treatments vary and range from changing or eliminating

environmen-tal factors, temporary sexual abstinence, and application of

cortisone ointments and topical lidocaine (jelly); to more radical treatments

such as surgical excision of the vestibular glands. A combination of treatment

modalities may be nec-essary. Treatment must be individualized, based on the

severity of patient symptoms and the sexual disability.

Some patients may benefit from

low-dose tricyclic medication (amitriptyline and desipramine) or fluoxetine to

help break the cycle of pain. Other limited reports suggest the use of calcium

citrate to change the urine composition by removing oxalic acid crystals. Those

advocating chang-ing the urine chemistry cite evidence to suggest that oxalic

acid crystals are particularly irritating when precipitated in the urine of

patients with high urinary oxalic acid composi-tion. Other modalities include

biofeedback, physical ther-apy with electrical stimulation, or intralesional

injections with triamcinolone and bupivacaine.

Vulvar Lesions

Sebaceous

or inclusion

cysts are caused by inflammatoryblockage of the sebaceous gland ducts and

are small, smooth, nodular masses, usually arising from the inner sur-faces of

the labia minora and majora, that contain cheesy, sebaceous material. They may

be easily excised if their size or position is troublesome.

The round ligament inserts into

the labium majus, car-rying an investment of peritoneum. On occasion,

peritoneal fluid may accumulate therein, causing a cyst of the canalof Nuck or hydrocele. If such cysts reach

symptomaticsize, excision is usually required.

Fibromas (fibromyomas)

arise from the connectivetissue and smooth muscle elements of vulva and vagina

and are usually small and asymptomatic. Sarcomatous change is extremely

uncommon, although edema and degenerative changes may make such lesions

suspicious for malignancy. Treatment is surgical excision when the lesions are

symp-tomatic or with concerns about malignancy. Lipomas appear much like fibromas, are rare, and are also treated

by excision if symptomatic.

Hidradenoma

is a rare lesion arising from the sweatglands of

the vulva. It is almost always benign, is usually found on the inner surface of

the labia majora, and is treated with excision.

Nevi are

benign, usually asymptomatic, pigmentedlesions whose importance is that they

must be distinguished from malignant melanoma, 3% to 4% of which occur on the

external genitalia in females. Biopsy of pigmented vulvar lesions may be

warranted, depending on clinical suspicion.

Related Topics