Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Airway Management

Airway Management: Anatomy

Airway Management

Expert airway management is an essential

skill in anesthetic practice.

ANATOMY

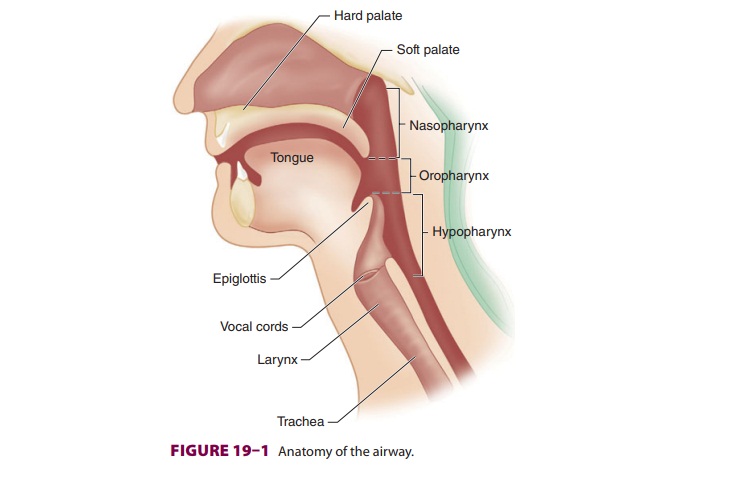

The upper airway consists of the

pharynx, nose, mouth, larynx, trachea, and main-stem bronchi. The mouth and

pharynx are also a part of the upper gas-trointestinal tract. The laryngeal

structures in part serve to prevent aspiration into the trachea.

There are two openings to the human

airway: the nose, which leads to the nasopharynx, and the mouth, which leads to

the oropharynx. These pas-sages are separated anteriorly by the palate, but

they join posteriorly in the pharynx ( Figure 19–1). The pharynx is a U-shaped

fibromuscular structure that extends from the base of the skull to the cricoid

car-tilage at the entrance to the esophagus. It opens ante-riorly into the

nasal cavity, the mouth, the larynx, and the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and

laryngo-pharynx, respectively. The nasopharynx is separated from the oropharynx

by an imaginary plane that extends posteriorly. At the base of the tongue, the

epiglottis functionally separates the orophar-ynx from the laryngopharynx (or

hypopharynx).

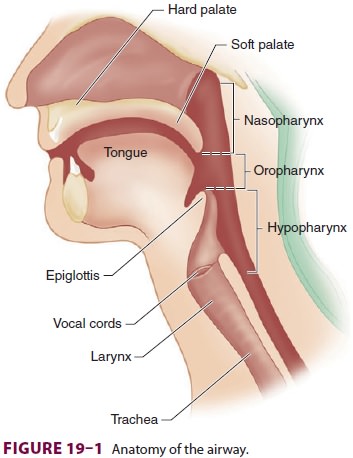

The epiglottis prevents aspiration by

covering the glottis—the opening of the larynx—during swal-lowing. The larynx

is a cartilaginous skeleton held together by ligaments and muscle. The larynx

is composed of nine cartilages ( Figure 19–2): thyroid, cricoid, epiglottic,

and (in pairs) arytenoid, cornicu-late, and cuneiform. The thyroid cartilage

shields the conus elasticus, which forms the vocal cords.

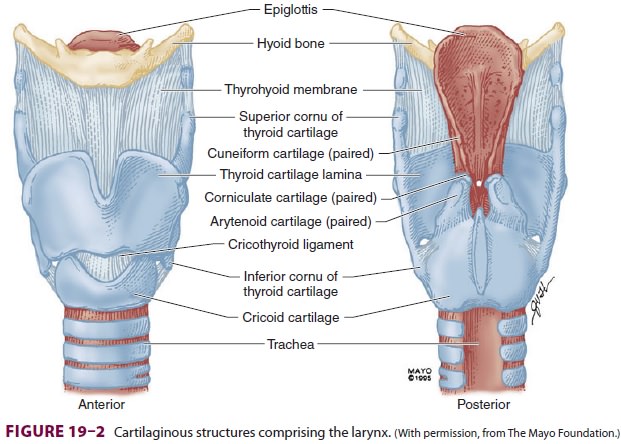

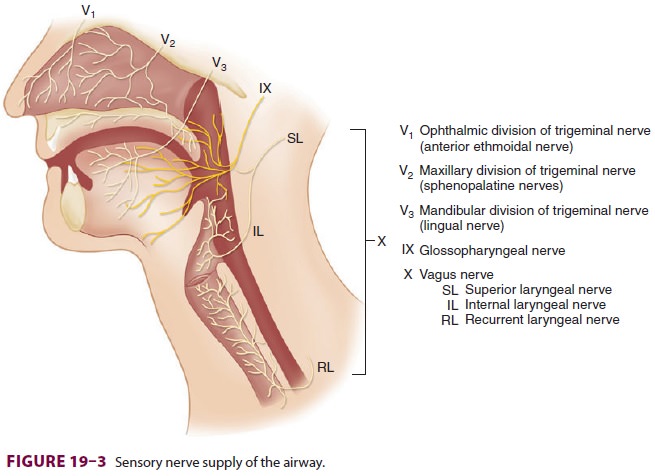

The sensory supply to the upper airway

is derived from the cranial nerves ( Figure 19–3). The mucous membranes of the nose

are innervated by the ophthalmic division (V1)

of the trigeminal nerve anteriorly (anterior ethmoidal nerve) and by the

maxillary division (V 2) posteriorly (sphenopala-tine nerves).

The palatine nerves provide sensory fibers from the trigeminal nerve (V) to the

supe-rior and inferior surfaces of the hard and soft pal-ate. The olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I)

innervates the nasal mucosa to provide the sense of smell. The lingual nerve (a

branch of the mandibular division [V3]

of the trigeminal nerve) and the glossopharyn-geal nerve (the ninth cranial

nerve) provide general sensation to the anterior two-thirds and posterior

one-third of the tongue, respectively. Branches of the facial nerve (VII) and

glossopharyngeal nerve provide the sensation of taste to those areas,

respec-tively. The glossopharyngeal

nerve also innervates the roof of the pharynx, the tonsils, and the

under-surface of the soft palate. The vagus

nerve (the tenth cranial nerve) provides sensation to the airway below the

epiglottis. The superior laryngeal branch of the vagus divides into an external

(motor) nerve and an internal (sensory) laryngeal nerve that pro-vide sensory

supply to the larynx between the epi-glottis and the vocal cords. Another

branch of the vagus, the recurrent

laryngeal nerve, innervates the larynx below the vocal cords and the

trachea.

The muscles of the larynx are innervated

by the recurrent laryngeal nerve, with the exception of the cricothyroid

muscle, which is innervated by the exter-nal (motor) laryngeal nerve, a branch

of the superior laryngeal nerve. The posterior cricoarytenoid mus-cles abduct

the vocal cords, whereas the lateral crico-arytenoid muscles are the principal

adductors.

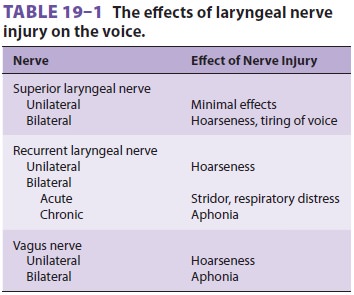

Phonation involves complex simultaneous

actions by several laryngeal muscles. Damage to the motor nerves innervating

the larynx leads

to a spectrum of speech disorders ( Table 19–1).

Unilateral denervation of a cricothyroid muscle causes very subtle clinical

findings. Bilateral palsy of the superior laryngeal nerve may result in hoarse-ness

or easy tiring of the voice, but airway control is not jeopardized.

Unilateral paralysis of a recurrent

laryngeal nerve results in paralysis of the ipsilateral vocal cord, causing

deterioration in voice quality. Assuming intact superior laryngeal nerves, acute bilateral recurrent laryngeal

nerve palsy can result in stri-dor and respiratory distress because of the

remain-ing unopposed tension of the cricothyroid muscles. Airway problems are

less frequent in chronic bilat-eral

recurrent laryngeal nerve loss because of the development of various

compensatory mechanisms (eg, atrophy of the laryngeal musculature).

Bilateral injury to the vagus nerve

affects both the superior and the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Thus, bilateral

vagal denervation produces flaccid, midpositioned vocal cords similar to those

seen after administration of succinylcholine. Although phona-tion is severely

impaired in these patients, airway control is rarely a problem.

The blood supply of the larynx is

derived from branches of the thyroid arteries. The cricothyroid artery arises

from the superior thyroid artery itself, the first branch given off from the

external carotid artery, and crosses the upper cricothyroid membrane (CTM),

which extends from the cricoid cartilage to

the thyroid cartilage. The superior

thyroid artery is found along the lateral edge of the CTM.

The trachea begins beneath the cricoid

cartilage and extends to the carina, the point at which the right and left

main-stem bronchi divide (Figure 19–4). Anteriorly, the trachea consists

of cartilaginous rings; posteriorly, the trachea is membranous.

Related Topics