Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Preoperative Assessment, Premedication, & Perioperative Documentation

Documentation - Clinical Anesthesiology

DOCUMENTATION

Physicians should first and foremost

provide high-quality and efficient medical care. Secondly, they must document

the care that has been provided. Adequate documentation provides guidance to

those who may encounter the patient in the future. It permits others to assess

the quality of the care that was given and to provide risk adjustment of

outcomes. Adequate documentation is required for a physician to submit a bill

for his or her services. Finally, adequate and well-organized documenta-tion

(as opposed to inadequate and sloppy docu-mentation) supports a potential

defense case should a claim for medical malpractice be filed.

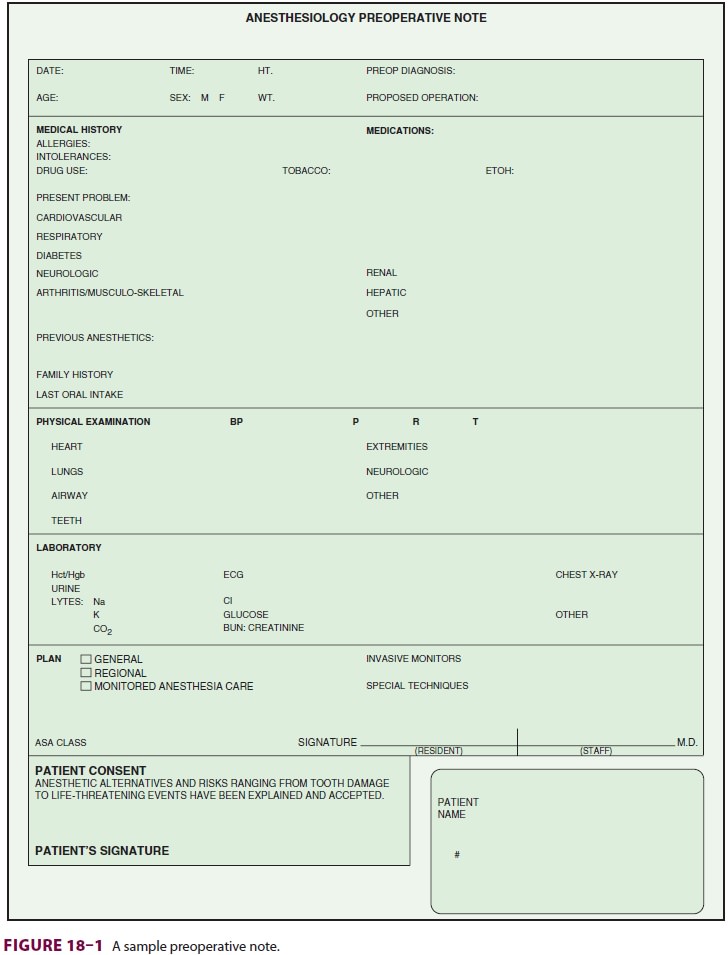

Preoperative Assessment Note

The preoperative assessment note should

appear in the patient’s permanent medical record and should describe pertinent

findings, including the medical history, anesthetic history, current medications

(and whether they were taken on the day of surgery), physical examination, ASA

physical status class, laboratory results, interpretation of imaging,

electro-cardiograms, and recommendations of any consul-tants. A comment is

particularly important when the consultant’s recommendation will not be

followed. As most North American hospitals are transitioning to electronic

medical records, the preanesthetic note will often appear as a standardized

form.

The preoperative note should briefly

describe the anesthetic plan and include a statement regard-ing informed

consent from the patient (or guardian). The plan should indicate whether

regional or general anesthesia (or sedation) will be used, and whether invasive

monitoring or other advanced techniques will be employed. Documentation of the

informed consent discussion sometimes takes the form of a narrative indicating

that the plan, alternative plans, and their advantages and disadvantages

(including their relative risks) were presented, understood, and accepted by

the patient. Alternatively, the patient may be asked to sign a special

anesthesia consent form that contains the same information. A sample

pre-anesthetic report form is illustrated in Figure 18–1.

In the United States, The Joint

Commission (TJC) requires an immediate preanesthetic reevalu-ation to determine

whether the patient’s status has changed in the time since the preoperative

evalu-ation was performed. Even when the elapsed time is less than a minute,

the bureaucracy will not be denied: the “box” must be checked to indicate that

there has been no interval change.

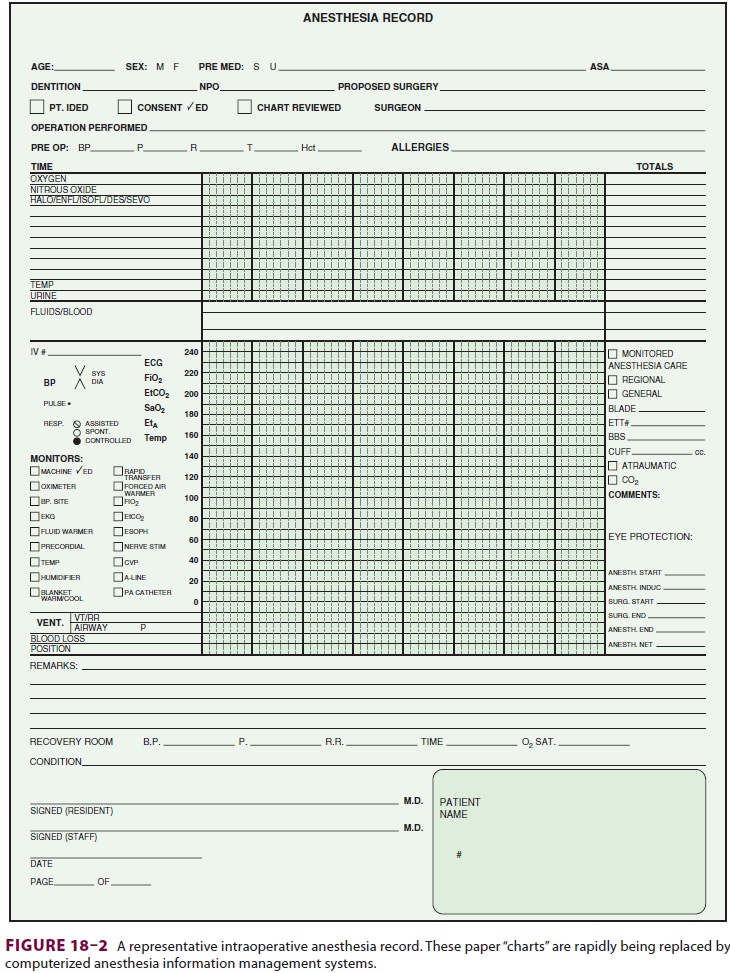

Intraoperative Anesthesia Record

The intraoperative anesthesia record (Figure 18–2)

serves many purposes. It functions as documenta-tion of intraoperative

monitoring, a reference for future anesthetics for that patient, and a source

of data for quality assurance. This record should be terse, pertinent, and

accurate. Increasingly, parts of the anesthesia record are generated

automati-cally and recorded electronically. Such anesthe-sia information

management systems (commonly abbreviated AIMS) have many theoretical and

practical advantages over the traditional paper record but also introduce all

the common pitfalls of

computerization, including the potential

for unrec-ognized recording of artifactual data, the possibility that

practitioners will find attending to the com-puter more interesting than

attending to the patient, and the inevitable occurrence of device and software

shutdowns. Regardless of whether the record is on paper or electronic it should

document the anes-thetic care in the operating room by including the following

elements:

Whether

there has been a preoperative check of the anesthesia machine and other

relevant equipment.

·

Whether

there has been a reevaluation of the patient immediately prior to induction of

anesthesia (a TJC requirement); this generally includes a review of the medical

record to search for any new laboratory results or consultation reports.

·

Time

of administration, dosage, and route of drugs given intraoperatively.

·

Intraoperative

estimates of blood loss and urinary output.

·

Results

of laboratory tests obtained during the operation.

·

Intravenous

fluids and any blood products administered.

·

Pertinent

procedure notes (such as for tracheal intubation or insertion of invasive

monitors).

·

A

notation regarding specialized intraoperative techniques such as the mode of

ventilation, or special techniques such as the use of hypotensive anesthesia,

one-lung ventilation, high-frequency jet ventilation, or cardiopulmonary

bypass.

·

Timing

and conduct of intraoperative events such as induction, positioning, surgical

incision, and extubation.

·

Unusual

events or complications (eg, arrhythmias).

·

Condition

of the patient at the time of release to the postanesthesia or intensive care

unit nurse.

By tradition and convention (and, in the

United States, according to practice guidelines) arterialblood pressure and

heart rate are recorded graphi-cally no less frequently than at 5-min

intervals. Data from other monitors are also usually entered graphi-cally,

whereas descriptions of techniques or compli-cations are described in text. In

some anesthetizing locations of most hospitals the computerized AIMS will be

unavailable. Unfortunately, the conventional, handwritten intraoperative

anesthetic record often proves inadequate for documenting critical inci-dents,

such as a cardiac arrest. In such cases, a sepa-rate text note inserted in the

patient’s medical record may be necessary. Careful recording of the timing of

events is needed to avoid discrepancies between multiple simultaneous records

(anesthesia record, nurses’ notes, cardiopulmonary resuscitation record, and

other physicians’ entries in the medical record). Such discrepancies are

frequently targeted by mal-practice attorneys as evidence of

incompetence,inaccuracy, or deceit. Incomplete, inaccurate, or illegible

records unnecessarily complicatedefending a physician against otherwise

unjustified allegations of malpractice.

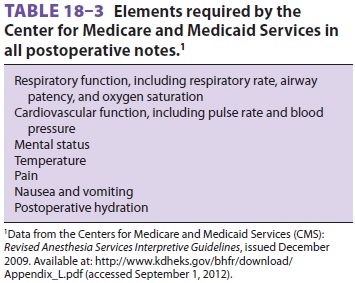

Postoperative Notes

The anesthesiologist’s immediate

responsibility to the patient does not end until the patient has recov-ered

from the effects of the anesthetic. After accom-panying the patient to the

postanesthesia care unit (PACU), the anesthesiologist should remain with the

patient until normal vital signs have been measured and the patient’s condition

is deemed stable. Before discharge from the PACU, a note should be written by

the anesthesiologist to document the patient’s recovery from anesthesia, any

apparent anesthesia-related complications, the immediate postoperative

condition of the patient, and the patient’s disposition (discharge to an

outpatient area, an inpatient ward, an intensive care unit, or home). In the

United States, as of 2009, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

require that certain elements be included in all postoperative notes ( Table 18–3).

Recovery from anesthesia should be assessed at least once within 48 h after

discharge from the PACU in all inpatients. Postoperative notes should document

the general condition of the patient, the presence or absence of any

anesthesia-related complications, and any mea-sures undertaken to treat such

complications.

Related Topics