Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Airway Management

Supraglottic Airway Devices

SUPRAGLOTTIC AIRWAY DEVICES

Supraglottic airway devices (SADs) are

used with both spontaneously and ventilated patients dur-ing anesthesia. They

have also been employed as conduits to aid endotracheal intubation when both

BMV and endotracheal intubation have failed. All SADs consist of a tube that is

connected to a respira-tory circuit or breathing bag, which is attached to a

hypopharyngeal device that seals and directs air-flow to the glottis, trachea,

and lungs. Additionally, these airway devices occlude the esophagus with

varying degrees of effectiveness, reducing gas dis-tension of the stomach.

Different sealing devices to prevent airflow from exiting through the mouth are

also available. Some are equipped with a port to suc-tion gastric contents.

None offer the protection from aspiration pneumonitis offered by a properly

sited, cuffed endotracheal tube.

Laryngeal Mask Airway

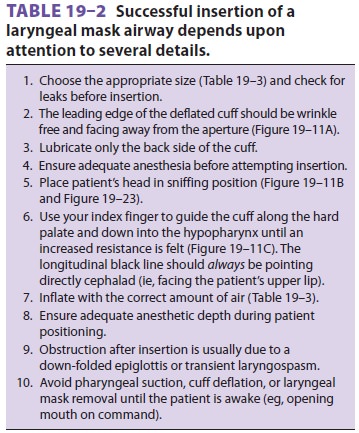

A laryngeal mask airway (LMA) consists

of a wide-bore tube whose proximal end connects to a breath-ing circuit with a

standard 15-mm connector, and whose distal end is attached to an elliptical

cuff that can be inflated through a pilot tube. The deflated cuff is lubricated

and inserted blindly into the hypophar-ynx so that, once inflated, the cuff

forms a low-pres-sure seal around the entrance to the larynx. This requires

anesthetic depth and muscle relaxation slightly greater than that required for

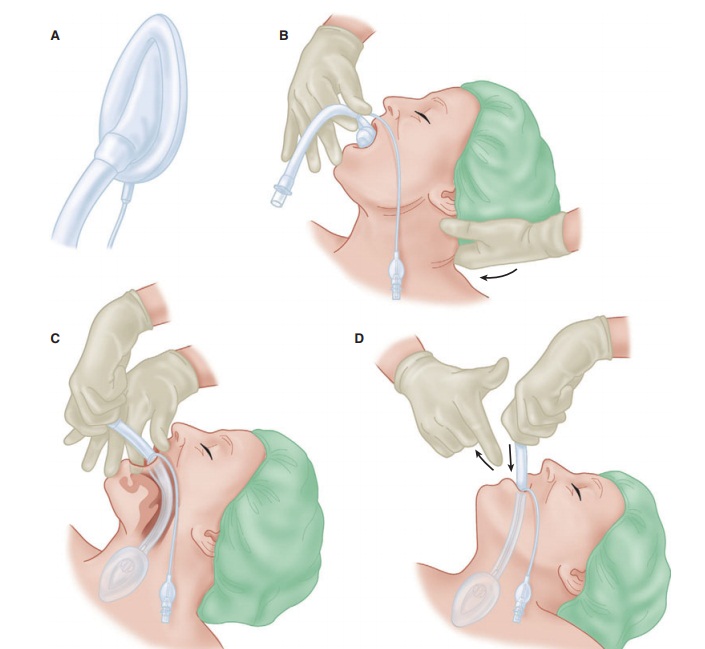

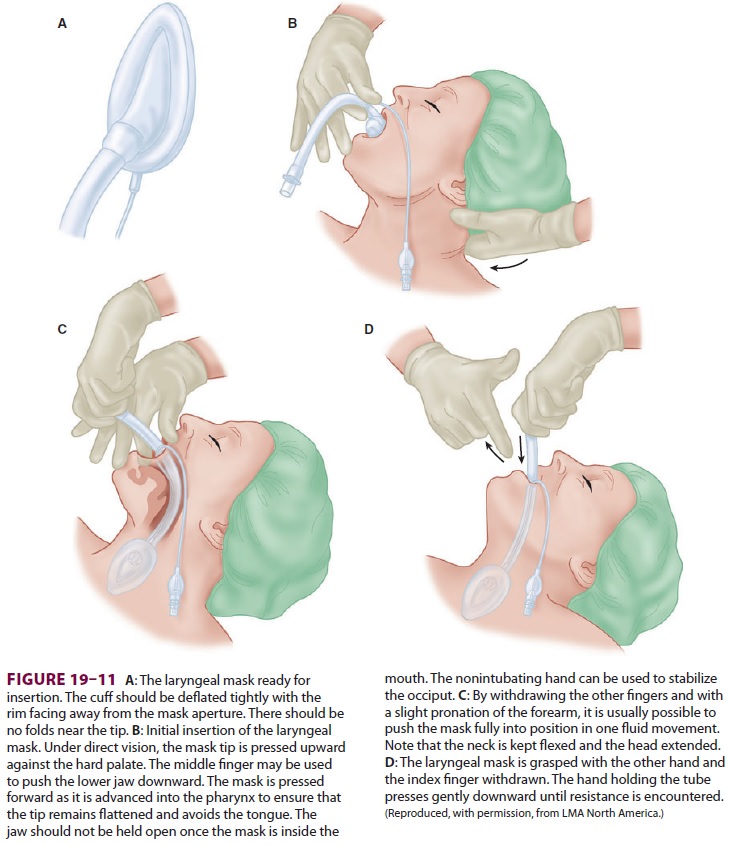

the insertion of an oral airway. Although insertion is relatively simple (Figure 19–11),

attention to detail will improve the success rate (Table 19–2). An ideally

positioned cuff is bordered by the base of the tongue superiorly, the pyriform

sinuses laterally, and the upper esophageal sphincter inferiorly. If the

esophagus lies within the rim of the cuff, gastric dis-tention and

regurgitation become possible. Anatomic variations prevent adequate functioning

in some patients. However, if an LMA is not func-tioning properly after

attempts to improve the “fit” of the LMA have failed, most practitioners will

try another LMA one size larger or smaller. The shaft can be secured with tape

to the skin of the face.The LMA partially protects the larynx from pharyngeal

secretions (but not gastric

regurgitation), and it should remain in place until the patient has regained

airway reflexes. This is usually signaled by coughing and mouth opening on

command. The LMA is available in many sizes (Table 19–3).

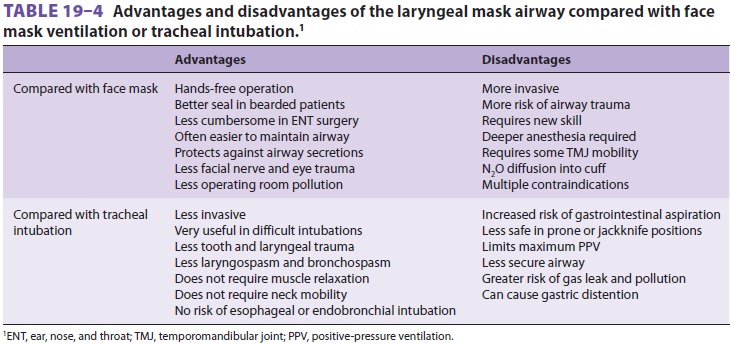

The LMA provides an alternative to

ventila-tion through a face mask or TT (Table 19–4). Relative contraindications for

the LMA include patients with pharyngeal pathology (eg, abscess), pharyngeal

obstruction, full stomachs (eg, preg-nancy, hiatal hernia), or low pulmonary

compli-ance (eg, restrictive airways disease) requiring peak inspiratory

pressures greater than 30 cm H2O. Traditionally, the LMA has been

avoided in patients

with bronchospasm or high airway

resistance, but new evidence suggests that because it is not placed in the

trachea, use of an LMA is associated with less bronchospasm than a TT. Although

it is clearly not a substitute for tracheal intubation, the LMA has proven

particularly helpful as a life-saving temporiz-ing measure in patients with

difficult airways (those who cannot be ventilated or intubated) because of

its ease of insertion and relatively

high success rate (95% to 99%). It has been used as a conduit for an intubating

stylet (eg, gum-elastic bougie), ven-tilating jet stylet, flexible FOB, or

small-diameter (6.0-mm) TT. Several LMAs are available that have been modified

to facilitate placement of a larger TT, with or without the use of a FOB.

Insertion can be performed under topical anesthesia and bilateral superior

laryngeal nerve blocks, if the airway must be secured while the patient is

awake.

Variations in LMA design include:

The ProSeal LMA, which permits passage of a gastric tube to decompress the stomachThe I-Gel, which uses a gel occluder rather than inflatable cuffThe Fastrach intubation LMA, which is designed to facilitate endotracheal intubation through the LMA deviceThe LMA CTrach, which incorporates a camera to facilitate passage of an endotracheal tube Sore throat is a common side ef fect follow-ing SAD use. Injuries to the lingual, hypoglossal, and recurrent laryngeal nerve have been reported. Correct device sizing, avoidance of cuff hyperinfla-tion, and gentle movement of the jaw during place-ment may reduce the likelihood of such injuries.

Esophageal–Tracheal Combitube

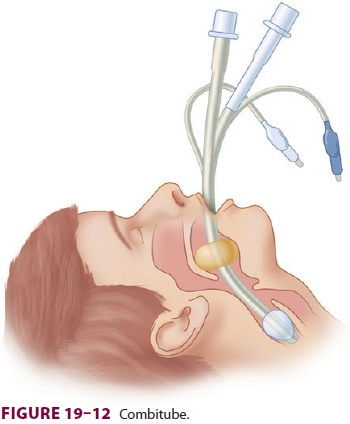

The esophageal–tracheal Combitube

consists of two fused tubes, each with a 15-mm connector on its proximal end (Figure 19–12).

The longer blue tube has an occluded distal tip that forces gas to exit through

a series of side perforations. The shorter clear tube has an open tip and no side

perforations. The Combitube is usually inserted blindly through the mouth and

advanced until the two black rings on the shaft lie between the upper and lower

teeth. The Combitube has two inflatable cuffs, a 100-mL proximal cuff and a

15-mL distal cuff, both of which should be fully inflated after placement. The

distal lumen of the Combitube usually comes to lie in the esophagus

approximately 95% of the time so that ventilation through the longer blue tube

will force gas out of the side perforations and into the lar-ynx. The shorter,

clear tube can be used for gastric

decompression. Alternatively, if the

Combitube enters the trachea, ventilation through the clear tube will direct

gas into the trachea.

King Laryngeal Tube

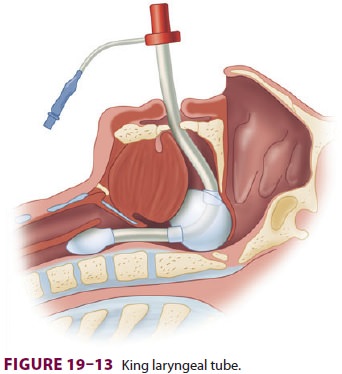

King laryngeal tubes (LTs) consist of

tube with a small esophageal balloon and a larger balloon for placement in the

hypopharynx (Figure

19–13). Both tubes inflate through one inflation line. The lungs are

inflated from air that exits between the two balloons. A suction port distal to

the esophageal balloon is present, permitting decompression of the stomach. The

LT is inserted and the cuffs inflated. Should ventilation prove difficult, the

LT is likely inserted too deep. Slightly withdrawing the device until

compliance improves ameliorates the situation.

Related Topics