Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Airway Management

Endotracheal Intubation

ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION

Endotracheal intubation is employed both

for the conduct of general anesthesia and to facilitate the ventilator

management of the critically ill.

Tracheal Tubes

Standards govern TT manufacturing

(American National Standard for Anesthetic Equipment; ANSI Z–79). TTs are most

commonly made from polyvi-nyl chloride. In the past, TTs were marked “I.T.” or

“Z–79” to indicate that they had been

implant tested to ensure nontoxicity. The shape and rigidity of TTs can be

altered by inserting a stylet. The patient end of the tube is beveled to aid

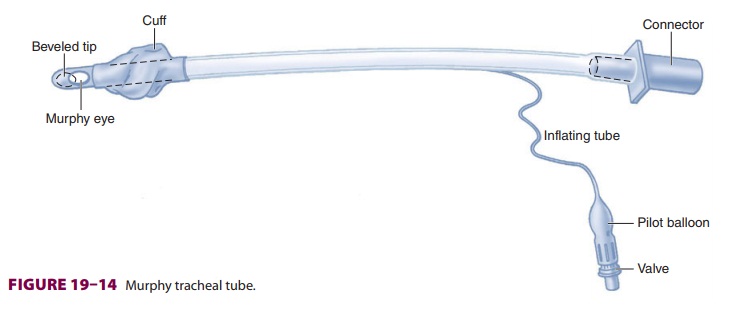

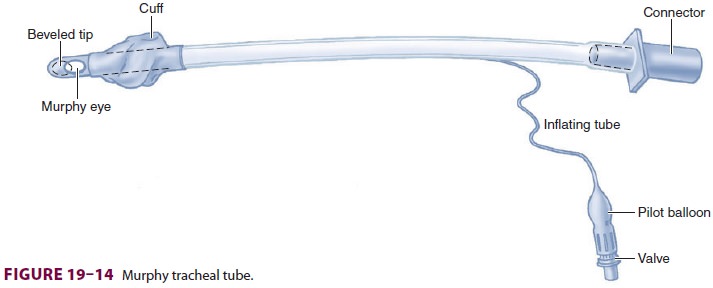

visualization and inser-tion through the vocal cords. Murphy tubes have a hole

(the Murphy eye) to decrease the risk of occlu-sion, should the distal tube

opening abut the carina or trachea ( Figure 19–14).

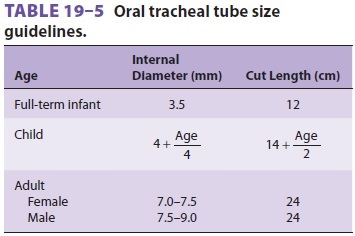

Resistance to airflow depends primarily on tube diameter, but is also affected by tube length and curvature. TT size is usually designated in millime-ters of internal diameter, or, less commonly, in the French scale (external diameter in millimeters mul-tiplied by 3). The choice of tube diameter is always a compromise between maximizing flow with a larger size and minimizing airway trauma with a smaller size (Table 19–5).Most adult TTs have a cuff inflation system con-sisting of a valve, pilot balloon, inflating tube, and cuff (Figure 19–14). The valve prevents air loss after cuff inflation. The pilot balloon provides a gross indication of cuff inflation. The inflating tube con-nects the valve to the cuff and is incorporated into the tube’s wall. By creating a tracheal seal, TT cuffs permit positive-pressure ventilation and reduce the likelihood of aspiration. Uncuffed tubes are often used in infants and young children to minimize the risk of pressure injury and postintubation croup; however, in recent years, cuffed pediatric tubes have been increasingly favored.

There are two major types of cuffs: high

pres-sure (low volume) and low pressure (high volume). High-pressure cuffs are

associated with more isch-emic damage to the tracheal mucosa and are less

suit-able for intubations of long duration. Low-pressure cuffs may increase the

likelihood of sore throat (larger mucosal contact area), aspiration,

spontane-ous extubation, and difficult insertion (because of the floppy cuff ).

Nonetheless, because of their lower incidence of mucosal damage, low-pressure

cuffs are generally employed.

Cuff pressure depends on several

factors: infla-tion volume, the diameter of the cuff in relation to the

trachea, tracheal and cuff compliance, and intrathoracic pressure (cuff

pressures increase with coughing). Cuff pressure may increase during gen-eral

anesthesia from diffusion of nitrous oxide from the tracheal mucosa into the TT

cuff.

TTs have been modified for a variety of

spe-cialized applications. Flexible, spiral-wound, wire-reinforced TTs (armored

tubes) resist kinking and may prove valuable in some head and neck surgical

procedures or in the prone patient. If an armored tube becomes kinked from

extreme pressure (eg, an awake patient biting it), however, the lumen will

often remain permanently occluded, and the tube will need replacement. Other

specialized tubes include micro-laryngeal tubes, double-lumen endotracheal

tubes (to facilitate lung isolation and one-lung ventilation), endotracheal

tubes equipped with bronchial block-ers (to facilitate lung isolation and

one-lung ventila-tion), metal tubes designed for laser airway surgery to reduce

fire hazards, and preformed curved tubes for nasal and oral intubation in head

and neck surgery.

Related Topics