Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Airway Management

Techniques of Direct and Indirect Laryngoscopy & Intubation

TECHNIQUES OF DIRECT AND INDIRECT LARYNGOSCOPY & INTUBATION

Indications for Intubation

Inserting a tube into the trachea has

become a routine part of delivering a general anesthetic. Intubation is not a

risk-free procedure, and not all patients receiv-ing general anesthesia require

it. A TT is generally placed to protect the airway and for airway access.

Intubation is indicated in patients who are at risk of aspiration and in those

undergoing surgical proce-dures involving body cavities or the head and neck.

Mask ventilation or ventilation with an LMA is usu-ally satisfactory for short

minor procedures such as cystoscopy, examination under anesthesia, inguinal

hernia repairs, extremity surgery, and so forth.

Preparation for Direct Laryngoscopy

Preparation for intubation includes

checking equip-ment and properly positioning the patient. The TT should be

examined. The tube’s cuff inflation system can be tested by inflating the cuff

using a 10-mL syringe. Maintenance of cuff pressure after detachingthe syringe ensures proper cuff and valve

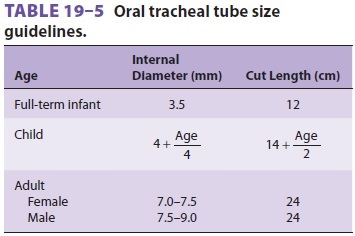

function.Some anesthesiologists cut the TT to a preset length to decrease the

dead space, the risk of bronchial intubation, and the risk of occlusion from

tube kink-ing (Table 19–5). The connector should be pushed firmly into the tube

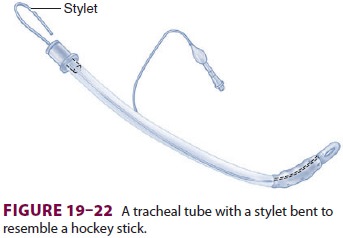

to decrease the likelihood of dis-connection. If a stylet is used, it should be

inserted

into the TT, which is then bent to resemble a hockey stick (Figure 19–22). This shape facilitates intuba-tion of an anteriorly positioned larynx. The desired blade is locked onto the laryngoscope handle, and bulb function is tested. The light intensity should remain constant even if the bulb is jiggled. A blink-ing light signals a poor electrical contact, whereas fading indicates depleted batteries. An extra handle, blade, TT (one size smaller than the anticipated optimal size), and stylet should be immediately available. A functioning suction unit is needed to clear the airway in case of unexpected secretions, blood, or emesis.

Successful intubation often depends on correct

patient positioning. The patient’s head should be level with the

anesthesiologist’s waist or higher to prevent unnecessary back strain during

laryngoscopy.

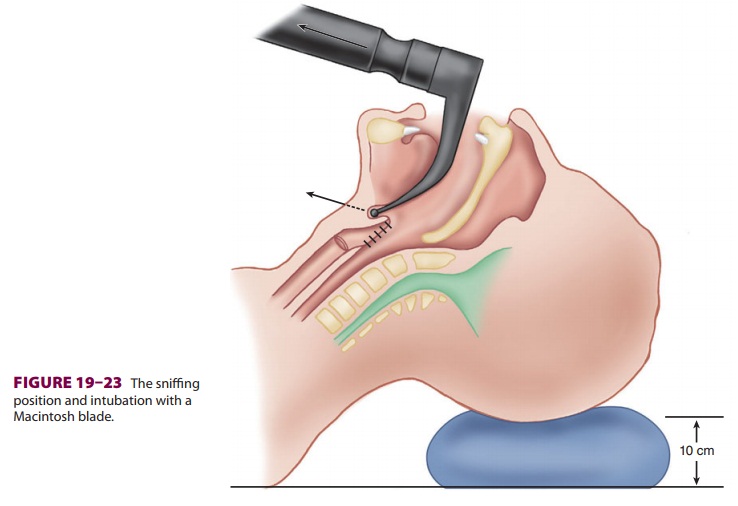

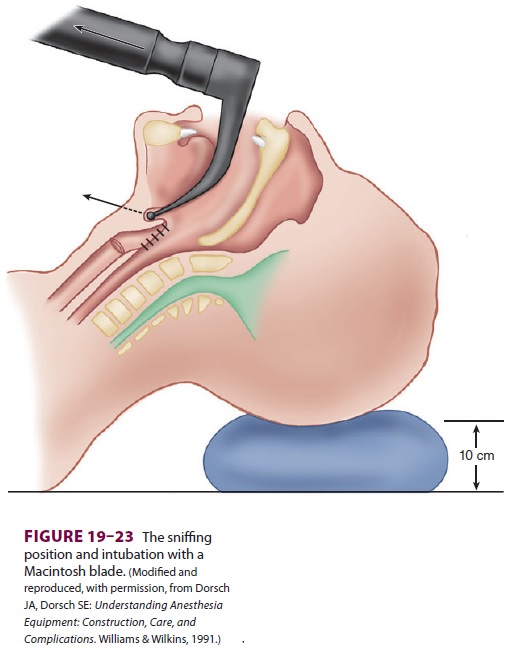

Direct laryngoscopy displaces pharyngeal

soft tissues to create a direct line of vision from the mouth to the glottic

opening. Moderate head eleva-tion (5–10 cm above the surgical table) and

exten-sion of the atlantooccipital joint place the patient in the desired

sniffing position (Figure 19–23). The lower portion of the

cervical spine is flexed by rest-ing the head on a pillow or other soft

support.

Preparation for induction and intubation

also involves routine preoxygenation. Administration of 100% oxygen provides an

extra margin of safety in

case the patient is not easily

ventilated after induc-tion. Preoxygenation can be omitted in patients who

object to the face mask; however, failing to preoxy-genate increases the risk

of rapid desaturation fol-lowing apnea.

Because general anesthesia abolishes the

pro-tective corneal reflex, care must be taken during this period not to injure

the patient’s eyes by uninten-tionally abrading the cornea. Thus, the eyes are

rou-tinely taped shut, often after applying an ophthalmic ointment before

manipulation of the airway.

Orotracheal Intubation

The laryngoscope is held in the left

hand. With the patient’s mouth opened the blade is introduced into the right

side of the oropharynx—with care to avoid the teeth. The tongue is swept to the

left and up into the floor of the pharynx by the blade’s flange. Successful

sweeping of the tongue leftward clears the view for TT placement. The tip of a

curved blade is usually inserted into the vallecula, and the straight blade tip

covers the epiglottis. With either blade, the handle is raised up and away from

the patient in a plane perpendicular to the patient’s mandible to expose the

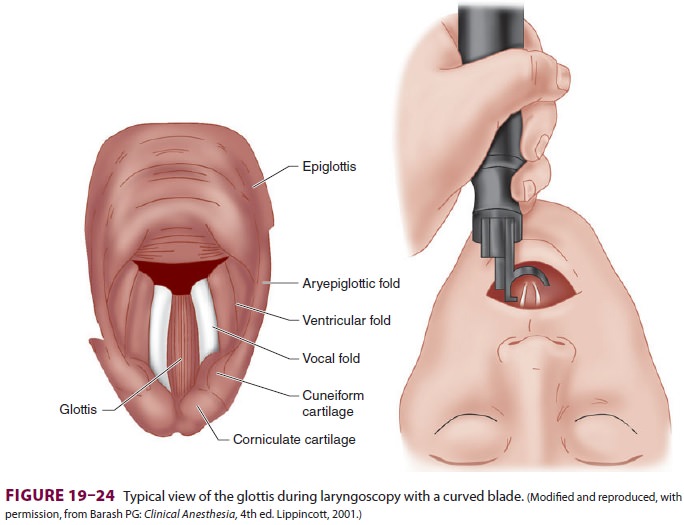

vocal cords (Figure

19–24). Trapping a lip between the teeth and the blade and leverage

on the teeth are avoided. The TT is taken with the right hand, and its tip is

passed through the abducted vocal cords. The “backward, upward, rightward,

pressure” (BURP) maneuver applied externally moves an anteriorly positioned

glottis posterior to facilitate visualiza-tion of the glottis. The TT cuff

should lie in the upper trachea, but beyond the larynx. The laryngo-scope is

withdrawn, again with care to avoid tooth damage. The cuff is inflated with the

least amount of air necessary to create a seal during positive-pressure

ventilation to minimize the

pressure transmitted to the tracheal

mucosa. Overinflation beyond 30 mm Hg may inhibit capil-lary blood flow,

injuring the trachea. Compressing the pilot balloon with the fingers is not a reliable method of determining

whether cuff pressure is either sufficient or excessive.

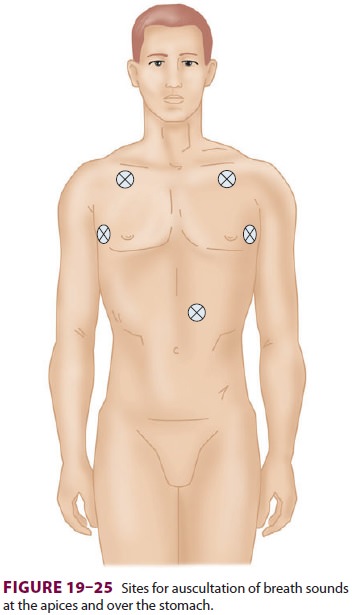

After intubation, the chest and

epigastrium are immediately auscultated, and a capnographic trac-ing (the

definitive test) is monitored to ensure intratracheal location ( Figure 19–25).

If there is doubt as to whether the tube is in the esophagus or trachea, repeat

the laryngoscopy to confirm place-ment. End-tidal CO 2 will not be produced if there is no cardiac output.

FOB through the tube and visualization of the tracheal rings and carina will

likewise confirm correct placement. Otherwise, the tube is taped or tied to

secure its position.Although the persistent detection of CO2 by a

capnograph is the best confirmation of tracheal placement of a TT, it cannot

exclude bron-chial intubation. The earliest evidence of bronchial intubation

often is an increase in peak inspiratory pressure. Proper tube location can be

reconfirmed by palpating the cuff in the sternal notch while compressing the

pilot balloon with the other hand.The cuff should not be felt above the level

of the cricoid cartilage, because a prolongedintralaryngeal location may result

in postoperative hoarseness and increases the risk of accidental extubation.

Tube position can also be documented by chest radiography.

The description presented here assumes

an unconscious patient. Oral intubation is usually poorly tolerated by awake,

fit patients. Intravenous sedation, application of a local anesthetic spray in

the oropharynx, regional nerve block, and constant reassurance will improve

patient acceptance.

A failed intubation should not be

followed by identical repeated attempts. Changes must be made to increase the

likelihood of success, such as repositioning the patient, decreasing the tube

size, adding a stylet, selecting a different blade, using an indirect

laryngoscope, attempting a nasal route, or requesting the assistance of another

anesthesiolo-gist. If the patient is also difficult to ventilate with a mask,

alternative forms of airway management (eg, LMA, Combitube, cricothyrotomy with

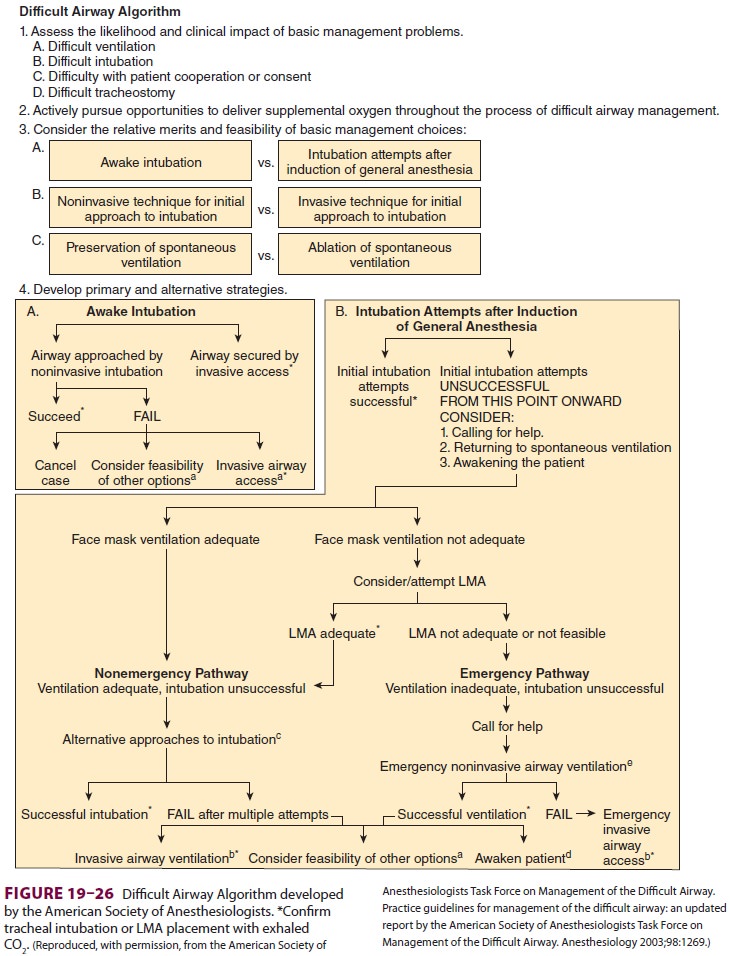

jet ven-tilation, tracheostomy) must be immediately pur-sued. The guidelines

developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists for the management of a

difficult airway include a treatment plan algorithm (Figure 19–26).

Use of video or indirect laryngoscopes

is dependent upon the design of the device. Some devices are placed midline

without the requirement to sweep the tongue from view. Other devices con-tain

channels to direct the endotracheal tube to the glottic opening. Practitioners

should be familiar with the features of available devices well in advance of

using one in a difficult airway situation. The com-bined use of a video

laryngoscope and an intubation

Difficult Airway Algorithm

Assess the likelihood and

clinical impact of basic management problems.

Difficult ventilation

Difficult intubation

Difficulty with patient

cooperation or consent

Difficult tracheostomy

Actively pursue

opportunities to deliver supplemental oxygen throughout the process of

difficult airway management.

Consider the relative merits and feasibility of basic management

choices:

bougie often can facilitate intubation,

when the endotracheal tube cannot be directed into the glot-tis despite good

visualization of the laryngeal open-ing (Figure 19–27).

Nasotracheal Intubation

Nasal intubation is similar to oral

intubation except that the TT is advanced through the nose and naso-pharynx

into the oropharynx before laryngoscopy. The nostril through which the patient

breathes most easily is selected in advance and prepared. Phenylephrine nose

drops (0.5% or 0.25%) vaso-constrict vessels and shrink mucous membranes. If

the patient is awake, local anesthetic ointment (for the nostril), spray (for

the oropharynx), and nerve blocks can also be utilized.

A TT lubricated with water-soluble jelly

is introduced along the floor of the nose, below the inferior turbinate, at an angle perpendicular tothe face.

The tube’s bevel should be directed later-ally away from the turbinates. To

ensure that the tube passes along the floor of the nasal cavity, the proximal

end of the TT should be pulled cephalad. The tube is gradually advanced, until

its tip can be visualized in the oropharynx. Laryngoscopy, as dis-cussed, reveals

the abducted vocal cords. Often the distal end of the TT can be pushed into the

trachea without difficulty. If difficulty is encountered, the tip of the tube

may be directed through the vocal cords with Magill forceps, being careful not

to damage the cuff. Nasal passage of TTs, airways, or nasogastric catheters

carries greater risk in patients with severe mid-facial trauma because of the

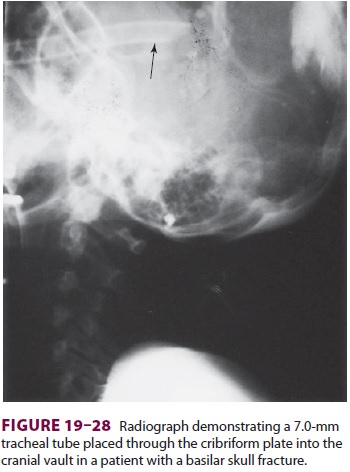

risk of intracranial placement (Figure 19–28).

Although less used today, blind nasal

intuba-tion of spontaneously breathing patients can be employed. In this

technique, after applying topi-cal anesthetic to the nostril and pharynx, a

breath-ing tube is passed through the nasopharynx. Using

breath sounds as a guide, it is directed

toward the glottis. When breath sounds are maximal, the anes-thetist advances

the tube during inspiration in an effort to blindly pass the tube into the

trachea.

Flexible Fiberoptic Intubation

Fiberoptic intubation (FOI) is routinely

performed in awake or sedated patients with problematic air-ways. FOI is ideal

for:

·

A

small mouth opening

·

Minimizing

cervical spine movement in trauma or rheumatoid arthritis

·

Upper

airway obstruction, such as angioedema or tumor mass

·

Facial

deformities, facial trauma

·

FOI

can be performed awake or asleep via oral or nasal routes.

·

Awake

FOI: predicted inability to ventilate by mask, upper airway obstruction

·

Asleep

FOI: Failed intubation, desire for minimal C spine movement in patients who

refuse awake intubation

·

Oral

FOI: Facial, skull injuries

·

Nasal

FOI: A poor mouth opening

When FOI is considered, careful planning

is necessary, as it will likely add to the anesthesia time prior to surgery.

Patients should be informed of the need for awake intubation as a part of the

informed consent process.

The airway is anesthetized with a local

anes-thetic spray, and patient sedation is provided, as tolerated.

Dexmedetomidine has the advantage of preserving respiration while providing

seda-tion. Airway anesthesia is discussed in the Case Discussion below.

If nasal FOI is planned, both nostrils

are pre-pared with vasoconstrictive drops. The nostril through which the

patient breathes more easily is identified. Oxygen can be insufflated through

the suction port and down the aspiration channel of the FOB to improve

oxygenation and blow secretions away from the tip.

Alternatively, a large nasal airway (eg,

36F) can be inserted in the contralateral nostril. The breath-ing circuit can

be directly connected to the end of this nasal airway to administer 100% oxygen

during laryngoscopy. If the patient is unconscious and not breathing

spontaneously, the mouth can be closed and ventilation attempted through the

single nasal airway. When this technique is used, adequacy of ventilation and

oxygenation should be confirmed by capnography and pulse oximetry. The

lubricated shaft of the FOB is introduced into the TT lumen. It is important to

keep the shaft of the broncho-scope relatively straight (Figure 19–29) so that if the

head of the bronchoscope is rotated in one direction, the distal end will move

to a similar degree and in the same direction. As the tip of the FOB passes

through the distal end of the TT, the epiglottis or glottis should be visible.

The tip of the bronchoscope is manipulated, as needed, to pass the abducted

cords.

Having an assistant thrust the jaw

forward or apply cricoid pressure may improve visualiza-tion in difficult

cases. If the patient is breathing

spontaneously, grasping the tongue with

gauze and pulling it forward may also facilitate intubation.

Once in the trachea, the FOB is advanced

to within sight of the carina. The presence of tracheal rings and the carina is

proof of proper position-ing. The TT is pushed off the FOB. The acute angle

around the arytenoid cartilage and epiglottis may prevent easy advancement of

the tube. Use of an armored tube usually decreases this problem due to its

greater lateral flexibility and more obtusely angled distal end. Proper TT

position is confirmed by viewing the tip of the tube an appropriate dis-tance

(3 cm in adults) above the carina before the FOB is withdrawn.

Oral FOI proceeds similarly, with the aid of various oral airway devices to direct the FOB toward the glottis and to reduce obstruction of the view by the tongue.

Related Topics