Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

Using Oneself in Listening

Using Oneself

in Listening

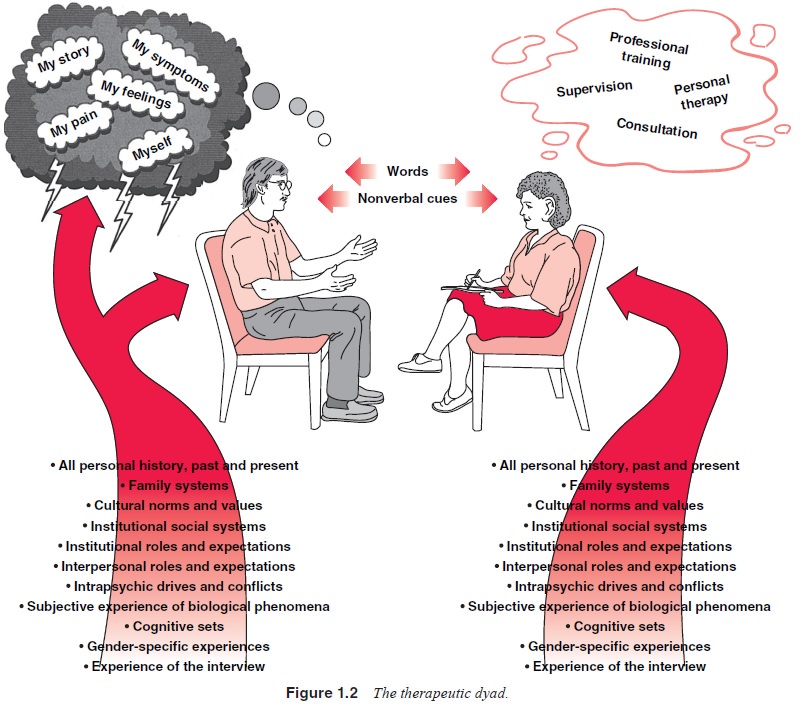

Understanding transference and countertransference

is crucial to effective listening. Tomkins, LeDoux, Damasio and Brothers have

given us a basic science, biological perspective on this proc-ess. However one

defines these terms, whatever one’s theoretical stance about these issues,

Harry Stack Sullivan (1969) had it right when he said that schizophrenics are

more human than anything else. To know ourselves is to begin to know our

patients more deeply. There are many ways to achieve this. Personal therapy is

one. Ongoing life experience is another. Supervision that empha-sizes one’s

emotional reactions to patients is still a third. Once we have started on the

road to achieving this understanding by therapy, supervision, or life

experience, continued listening to our patients, who teach us about ourselves

and others, becomes a lifelong method of growth.

To know oneself is to be aware that there are

certain com-mon human needs, wishes, fears, feelings and reactions. Every

person must deal in some way with attachment, dependence, authority, autonomy,

selfhood, values and ideals, remembered others, work, love, hate and loss. It

is unlikely that the psychia-trist can comprehend the patient without his own

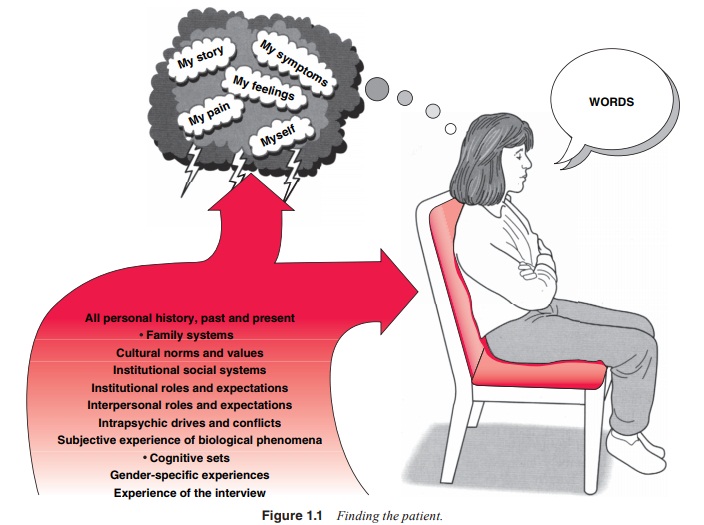

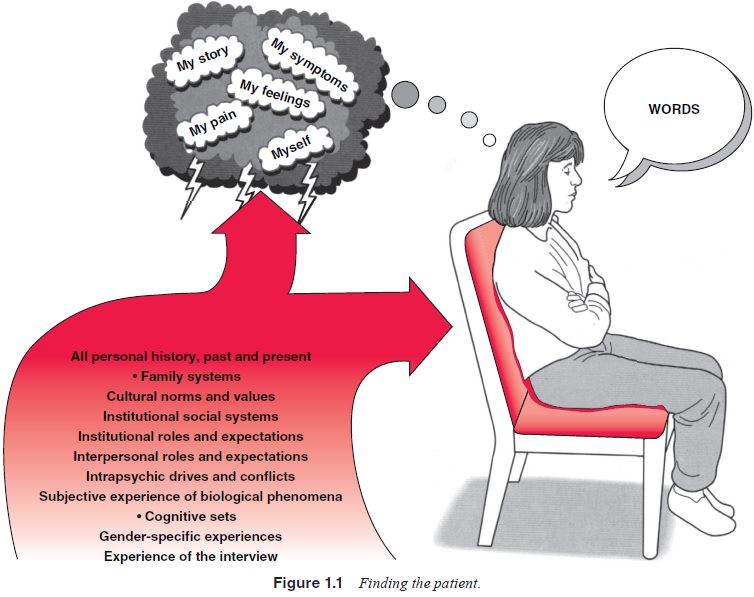

self-awareness. Thus, Figure 1.1 should really look like Figure 1.2. The most

psy-chotic patient in the world is still struggling with these universal human

functions.

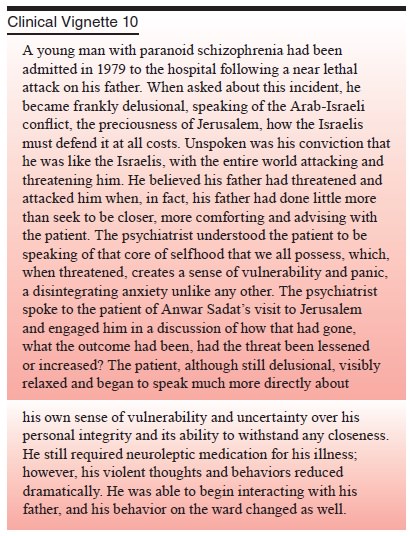

In this case, the psychiatrist was able to connect

with a patient’s inner experience in a manner that had a fairly dra-matic

impact on the clinical course. That is the goal of listen-ing. The art is

hearing the patient’s inner experience and then addressing it empathically,

enabling the patient to feel heard and affirmed. There are no rules about this,

and at any given point in a clinical encounter there are many ways to

accomplish it.

There are also many ways to respond that are

unhelpful and even retraumatizing. The skilled psychiatrist, just as she/he

never for-gets that it is the patient’s inner experience that is to be heard,

also never stops struggling to find just the right words, gestures, expressions

and inflections that say to a patient, “you have been understood”. The most

clever diagnostician or insightful inter-preter who cannot “connect” with the

patient in this manner will miss valuable information. This issue has been

addressed by writers who have pointed out how little understood are the

con-cepts of support and empathy (Peteet, 1982).

Being human is also to be a creature of habit and

pattern in linguistic, interpersonal, and emotional realms. The skilled

psychiatrist listens with this ever in mind. What we see in the interview, what

we hear in interactions, may be presumed to be repetitions of many other

events. The content may vary, but the form, motive, process and evolution are

generally universal for any given individual. This, too, is part of listening.

To know what is fundamentally human, to have a well-synthesized rigor-ous

theory, and to hear the person’s unique but repetitive ways of experiencing are

the essence of listening. These skills “find” the patient in all his/her

humanity, but then the psychiatrist must find the right communication that

allows the patient to feel “found”.

Related Topics