Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Connective tissue disorders

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus

Lupus

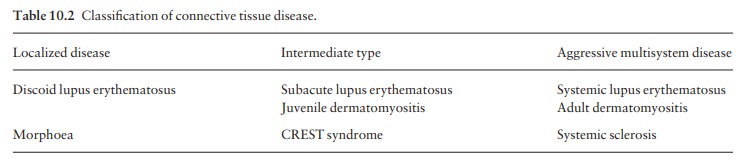

erythematosus (LE) is a good example of such a spectrum, ranging from the

purely cutaneous type (discoid LE), through patterns associated with some

internal problems (disseminated discoid LE and sub-acute cutaneous LE), to a

severe multisystem disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE; Table 10.2).

Systemic

lupus erythematosus

Cause

This

is unknown, but hereditary factors, e.g. com-plement deficiency and certain HLA

types, increase susceptibility. Particles looking like viruses have been seen

in endothelial cells, and in other tissues, but their role is not clear.

Patients with LE have autoantibodies to DNA, nuclear proteins and to other

normal antigens, and this points to an autoimmune cause. Exposure to sunlight

and artificial ultraviolet radiation (UVR), pregnancy and infection may

precipitate the disease or lead to flare-ups. Some drugs, such as hydralazine

and procainamide trigger SLE in a dose-dependent way, whereas others including

oral contraceptives, anti-convulsants, minocycline and captopril, precipitate

the disease just occasionally.

Presentation

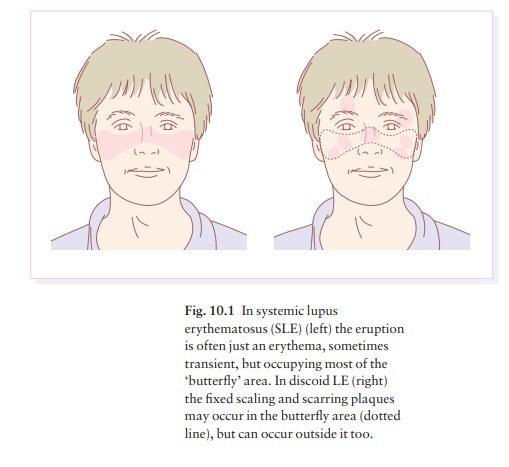

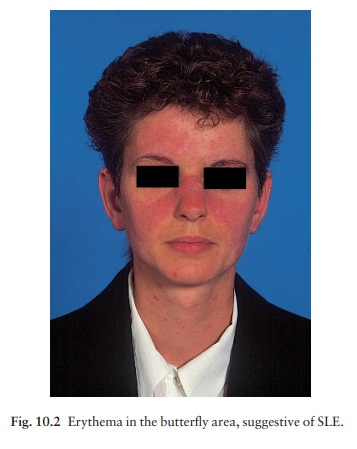

Typically,

but not always, the onset is acute. SLE is an uncommon disorder, affecting

women more often than men (in a ratio of about 8 : 1). The classic rash of

acute SLE is an erythema of the cheeks and nose in the rough shape of a

butterfly (Figs 10.1 and 10.2), with facial swelling. Occasionally, a few

blisters may be seen. Some patients develop widespread discoid papulosquamous

plaques very like those of discoid LE; others, about 20% of patients, have no

skin dis-ease at any stage.

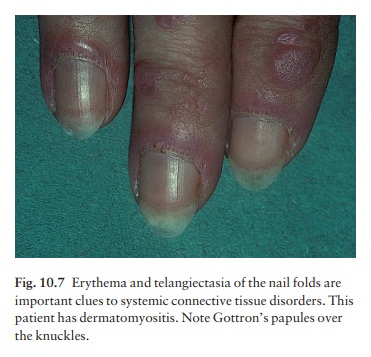

Other

dermatological features include peri-ungual telangiectasia (see Fig. 10.7),

erythema over the digits, hair fall (especially at the frontal margin of the

scalp), and photosensitivity. Ulcers may occur on the pal-ate, tongue or buccal

mucosa.

Course

The

skin changes may be transient, continuous or recurrent; they correlate well

with the activity of the systemic disease. Acute SLE may be associated with

fever, arthritis, nephritis, polyarteritis, pleurisy, pneu-monitis,

pericarditis, myocarditis and involvement of the central nervous system.

Internal involvement can be fatal, but the overall prognosis now is for about

three-quarters of patients to survive for 15 years. Renal involvement suggests

a poorer prognosis.

Complications

The skin disease may cause scarring or hyperpigmenta-tion, but the main dangers lie with damage to other organs and the side-effects of treatment, especially systemic steroids.

Differential diagnosis

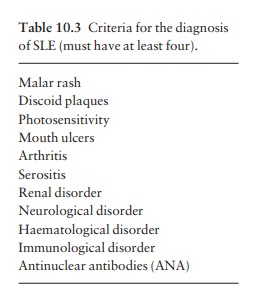

SLE

is a great imitator. Its malar rash can be confused with sunburn, polymorphic

light eruption and rosacea. The discoid

lesions are distinct-ive, but are also seen in discoid LE and in subacute

cutaneous LE. Occasionally, they look like psoriasis or lichen planus. The hair

fall suggests telogen effluvium. Plaques on the scalp may cause a scarring

alopecia. SLE should be suspected when a characteristic rash is combined with

fever, malaise and internal disease (Table 10.3).

Investigations

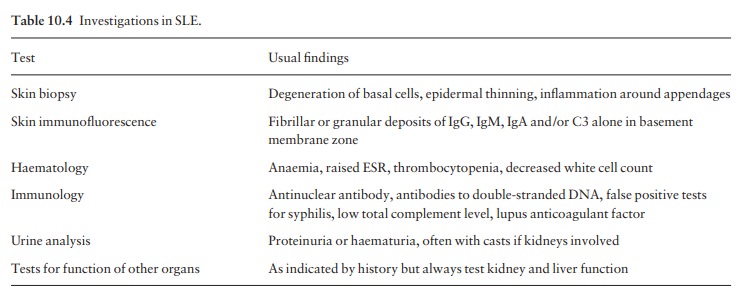

Conduct

a full physical examination, looking for internal disease. Biopsy of skin

lesions is worthwhile because the pathology and immunopathology are

dis-tinctive. There is usually some thinning of the epidermis,

Direct immunofluorescence is helpful: IgG, IgM, IgA and C3 are

found individually or together in a band-like pattern at the dermo-epidermal

junction of involved skin and often uninvolved skin as well. Relevant

laboratory tests are listed in Table 10.4.

Treatment

Systemic steroids are the mainstay of treatment, with bed rest needed during exacerbations. Large doses of prednisolone are often needed to achieve control, as assessed by symptoms, signs, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), total comple-ment level and tests of organ function. The dosage is then reduced to the smallest that suppresses the disease. Immunosuppressive agents, such as azathio-prine, cyclophosphamide and other drugs (e.g. antihypertensive therapy or anticon-vulsants) may also be needed.

Antimalarial drugs may help some patients with marked photosensitivity, as may

sunscreens. Intermittent intravenous infusions of gamma globulin show promise.

Long-term and regular follow-up is necessary.

1 Do

not wait for the laboratory to confirm that your patient has severe SLE: use

systemic steroids quickly if indicated by clinical findings.

2

A person

with aching joints and smallamounts of antinuclear antibodies probably does not

have SLE.

3

Once

committed to systemic steroids, adjusttheir dosage on clinical rather than

laboratory grounds.

Related Topics