Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Burn Injury

Acute or Intermediate Phase of Burn Care

ACUTE OR INTERMEDIATE PHASE OF BURN CARE

The acute or intermediate phase of burn care

follows the emergent/ resuscitative phase and begins 48 to 72 hours after the

burn injury. During this phase, attention is directed toward continued

assess-ment and maintenance of respiratory and circulatory status, fluid and

electrolyte balance, and gastrointestinal function. Infection pre-vention, burn

wound care (ie, wound cleaning, topical antibacterial therapy, wound dressing,

dressing changes, wound débridement, and wound grafting), pain management, and

nutritional support are priorities at this stage and will be discussed in

detail.

Airway obstruction caused by upper airway edema can

take as long as 48 hours to develop. Changes detected by x-ray and arte-rial

blood gases may occur as the effects of resuscitative fluid and the chemical

reaction of smoke ingredients with lung tissues be-come apparent. The arterial

blood gas values and other parameters determine the need for intubation or

mechanical ventilation.

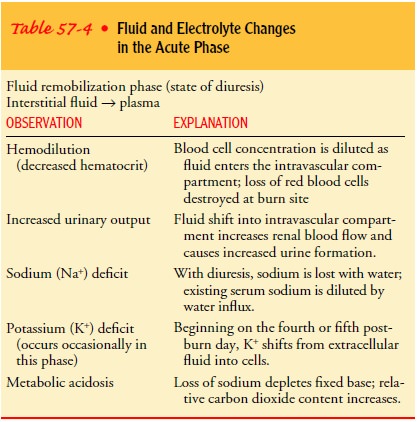

As capillaries regain integrity, at 48 or more

postburn hours, fluid moves from the interstitial to the intravascular

compartment and diuresis begins (Table 57-4). If cardiac or renal function is

inadequate, for instance in the elderly patient or in the patient with

preexisting cardiac disease, fluid overload occurs and symp-toms of congestive

heart failure may result. Early detection allows for early intervention and carefully

calculated fluid intake. Vasoactive medications, diuretics, and fluid

restric-tion may be used to support circulatory function and prevent congestive

heart failure and pulmonary edema.

Cautious

administration of fluids and electrolytes continues during this phase of burn

care because of the shifts in fluid from the interstitial to intravascular

compartments, losses of fluid from large burn wounds, and the patient’s

physiologic responses to the burn injury. Blood components are administered as

needed to treat blood loss and anemia.

Fever is common in burn patients after burn shock resolves. A resetting of the core body temperature in severely burned patients results in a body temperature a few degrees higher than normal for several weeks after the burn. Bacteremia and septicemia also cause fever in many patients. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) and hypo-thermia blankets may be required to maintain body temperature in a range of 37.2° to 38.3°C (99° to 101°F) to reduce metabolic stress and tissue oxygen demand.

Central

venous, peripheral arterial, or pulmonary artery ther-modilution catheters may

be required for monitoring venous and arterial pressures, pulmonary artery

pressures, pulmonary capillary wedge pressures, or cardiac output. Generally,

however, invasive vascular lines are avoided unless essential because they

provide an additional port for infection in an already greatly compromised

patient.

Infection

progressing to septic shock is the major cause of death in patients who have

survived the first few days after a major burn. The immunosuppression that

accompanies exten-sive burn injury places the patient at high risk for sepsis.

The infection that begins within the burn site may spread to the bloodstream.

Infection Prevention

Despite

aseptic precautions and the use of topical antimicrobial agents, the burn wound

is an excellent medium for bacterial growth and proliferation. Bacteria such as

Staphylococcus, Proteus, Pseudo-monas,

Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella find

optimal conditions forgrowth within the burn wound. The burn eschar is a

nonviable crust with no blood supply; therefore, neither polymorpho-nuclear

leukocytes or antibodies nor systemic antibiotics can reach the area.

Phenomenal numbers of bacteria—more than 1 billion per gram of tissue—may

appear and subsequently spread to the bloodstream or release their toxins,

which reach distant sites. Staph-ylococci and enterococci are the organisms

responsible for more than 50% of nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients

with burn injuries. Fungi such as Candida

albicans also grow easily in burn wounds.

When

the burn wound is healing through spontaneous re-epithelialization or is being

prepared for skin grafting, it must be protected from sepsis. Burn wound sepsis

has these characteristics:

·

105

bacteria per gram of tissue

·

Inflammation

·

Sludging and thrombosis of

dermal blood vessels

The primary source of bacterial infection appears

to be the patient’s intestinal tract, the source of most microbes. The

intestinal mucosa normally serves as a barrier to keep the internal

environ-ment free from a variety of pathogens. After a severe burn injury, the

intestinal mucosal barrier becomes markedly permeable. Be-cause of this impaired

intestinal mucosal barrier, the disturbed microbial flora and endotoxins found

in the intestinal lumen pass freely into the systemic circulation, finally

causing infection. If the intestinal mucosa receives some type of protection

against permeability change, infection could be avoided. Early enteral feeding

is one step to help avoid this increased intestinal perme-ability and prevent

early endotoxin translocation (Cioffi, 2000; Peng, Yuan & Ziao, 2001).

Infection

impedes burn wound healing by promoting excessive inflammation and damaging

tissue. A major secondary source of pathogenic microbes is the environment.

Infection control is a major role of the burn team in providing appropriate

burn wound care. Cap, gown, mask, and gloves are worn while caring for the

patient with open burn wounds. Clean technique is used when caring directly for

burn wounds.

Tissue

specimens are obtained for culture regularly to moni-tor colonization of the

wound by microbial organisms. These may be swab, surface, or tissue biopsy

cultures. Swab or surface cultures are noninvasive, simple, and painless.

However, data ob-tained from such cultures apply only to the area sampled;

there-fore, invasive wound biopsy cultures may be required. Antibiotics are

seldom prescribed prophylactically because of the risk of pro-moting resistant

strains of bacteria. Systemic antibiotics are ad-ministered when there is

documentation of burn wound sepsis or other positive cultures such as urine,

sputum, or blood. Sensitivity of the organisms to the prescribed antibiotics

should be deter-mined before administration. Several parenteral antimicrobial

agents may be given together to treat the infection. Careful at-tention is paid

to antibiotic use in the burn unit because inap-propriate use of antibiotics

significantly affects the microbial flora present in the unit.

Wound Cleaning

Various

measures are used to clean the burn wound. Hydro-therapy

in the form of shower carts, individual showers, and bedbaths can be used

to clean the wounds. Total immersion hydro-therapy is performed in some

settings. Because of the high risk of infection and sepsis, the use of plastic

liners and thorough de-contamination of hydrotherapy equipment and wound care

areas are necessary to prevent cross-contamination. Tap water alone can be used

for burn wound cleansing. The temperature of the water is maintained at 37.8°C (100°F), and the temperature

of the room should be maintained between 26.6° and 29.4°C (80° to 85°F). Hydrotherapy, in

whatever form, should be limited to a 20- to 30-minute period to prevent

chilling of the patient and additional metabolic stress.

During the bath, the patient is encouraged to be as

active as possible. Hydrotherapy provides an excellent opportunity for

ex-ercising the extremities and cleaning the entire body. When the patient is

removed from the tub after the bath, any residue ad-hering to the body is

washed away with a clear water spray or shower. Unburned areas, including the

hair, must be washed reg-ularly as well. At the time of wound cleaning, all

skin is inspected for any hints of redness, breakdown, or local infection. Hair

in and around the burn area, except the eyebrows, should be clipped short.

Intact blisters may be left, but the fluid should be aspirated with a needle

and syringe and discarded.

Conscientious

management of the burn wound is essential. When nonviable loose skin is

removed, aseptic conditions must be established. Wound cleaning is usually

performed at least daily in wound areas that are not undergoing surgical

intervention. When the eschar begins to separate from the viable tissue beneath

(approximately 1.5 to 2 weeks after the burn), more frequent cleaning and

débridement may be in order.

After

the burn wounds are cleaned, they are gently patted with towels and the

prescribed method of wound care is performed. Physician preferences, the

availability of skilled nursing staff, and resources in terms of number of

personnel, supplies, and time must be considered in choosing the best method

for a given pa-tient. Whatever the method, the goal is to protect the wound

from overwhelming proliferation of pathogenic organisms and invasion of deeper

tissues until either spontaneous healing or skin grafting can be achieved.

Patient comfort and ability to participate in the

prescribed treatment are also important considerations. Wound care proce-dures,

particularly tub baths, are metabolically stressful. There-fore, the patient is

assessed for signs of chilling, fatigue, changesin hemodynamic status, and pain

unrelieved by analgesic med-ications or relaxation techniques.

Topical Antibacterial Therapy

There is general agreement that some form of

antimicrobial ther-apy applied to the burn wound is the best method of local

care in extensive burn injury. Topical antibacterial therapy does not

ster-ilize the burn wound; it simply reduces the number of bacteria so that the

overall microbial population can be controlled by the body’s host defense

mechanisms. Topical therapy promotes con-version of the open, dirty wound to a

closed, clean one.

Criteria

for choosing a topical agent include the following:

·

It is effective against

gram-negative organisms, Pseudomonasaeruginosa,

Staphylococcus aureus, and even fungi.

·

It is clinically effective.

·

It penetrates the eschar but

is not systemically toxic.

·

It does not lose its

effectiveness, allowing another infection to develop.

·

It is cost-effective,

available, and acceptable to the patient.

·

It is easy to apply,

minimizing nursing care time.

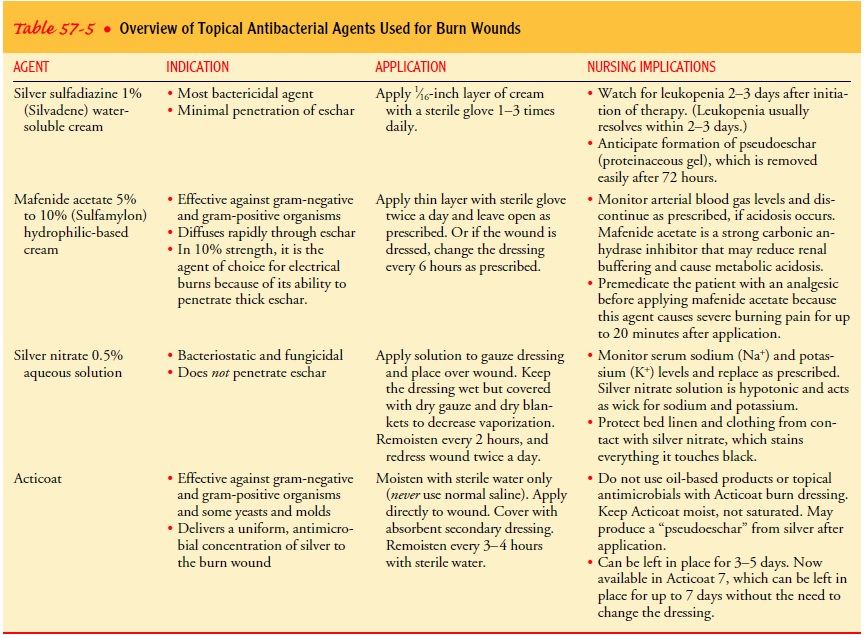

The three most commonly used topical agents are

silver sulfadi-azine (Silvadene), silver nitrate, and mafenide acetate

(Sulfamylon). These agents are described in Table 57-5. Many other topical

agents are available, including povidone–iodine ointment 10% (Betadine),

gentamicin sulfate, nitrofurazone (Furacin), Dakin’s solution, acetic acid,

miconazole, and chlortrimazole. Bacitracin may be used for facial burns or on

skin grafts initially.

A

newer product used in burn wound care is Acticoat Anti-microbial Barrier

dressing. Acticoat is a silver-coated dressing approved for treatment of burn

wounds and donor sites. This

dressing is kept moist with water for a controlled, sustained re-lease of

silver over the wound to provide an antimicrobial barrier. Acticoat has been

shown to have a better antimicrobial perfor-mance than the traditional

silver-based products commonly used in burn wound treatment. Acticoat is also

cost-effective. The dressing can be left in place for up to 5 days, decreasing

patient discomfort, the cost of dressing supplies, and nursing time for

dressing changes. The dressing has been shown clinically to be very effective

for prevention of burn wound infection (Yin, Langford & Burrell, 1999).

No single topical medication is universally

effective. Using dif-ferent agents at different times in the postburn period

may be necessary. Bacteriologic cultures are required to monitor the effect of

topical medications. Prudent use and alternation of anti-microbial agents

result in less resistant strains of bacteria, greater effectiveness of the

agents, and a decreased risk of sepsis.

Before a topical agent is reapplied, the previously applied top-ical agent must be thoroughly removed. The number of times the dressings are changed and soaked is planned to promote optimal therapeutic use of the topical agent.

Wound Dressing

When

the wound is clean, the burned areas are patted dry and the prescribed topical

agent is applied; the wound is then covered with several layers of dressings. A

light dressing is used over joint areas to allow for motion (unless the

particular area has a graft and motion is contraindicated). A light dressing is

also applied over areas for which a splint has been designed to conform to the

body contour for proper positioning. Circumferential dressings should be

applied distally to proximally. If the hand or foot is burned, the fingers and

toes should be wrapped individually to promote adequate healing.

Burns

to the face may be left open to air once they have been cleaned and the topical

agent has been applied. Careful attention must be given to burns left exposed

to ensure that they do not dry out and convert to a deeper burn.

Close communication and cooperation among the

patient, surgeon, nurse, and other health care team members are essential for

optimal burn wound care. Different wound areas on a given patient may require a

variety of wound care techniques. Diagrams posted at the bedside are useful to

inform staff of the current pre-scription for wound care, splints to be applied

over dressings, and the exercise regimen to be followed before dressings are

reapplied.

OCCLUSIVE METHOD

There

is a role for occlusive dressings in treating specific wounds. An occlusive

dressing is a thin gauze that is impregnated with a topical antimicrobial agent

or that is applied after topical anti-microbial application. Occlusive

dressings are most often used over areas with new skin grafts. Their purpose is

to protect the graft, promoting an optimal condition for its adherence to the

recipient site. Ideally, these dressings remain in place for 3 to 5 days, at

which time they are removed for examination of the graft.

When

these dressings are applied, precautions are taken to prevent two body surfaces

from touching, such as fingers or toes, ear and scalp, the areas under the

breasts, any point of flexion, or between the genital folds. Functional body

alignment positions are maintained by using splints or by careful positioning

of the patient.

Dressing Changes

Dressings

are changed in the patient’s unit, hydrotherapy room, or treatment area

approximately 20 minutes after an analgesic agent is administered. They may

also be changed in the operat-ing room after the patient is anesthetized. A

mask, goggles, hair cover, disposable plastic apron or cover gown, and gloves

are worn by health care personnel when removing the dressings. The outer

dressings are slit with blunt scissors, and the soiled dress-ings are removed

and disposed of in accordance with established procedures for contaminated

materials.

Dressings that adhere to the wound can be removed

more comfortably if they are moistened with tap water or if the patient is allowed

to soak for a few moments in the tub. The remaining dressings are carefully and

gently removed. The patient may partic-ipate in removing the dressings,

providing some degree of control over this painful procedure. The wounds are

then cleaned and débrided to remove debris, any remaining topical agent,

exudate, and dead skin. Sterile scissors and forceps may be used to trim loose

eschar and encourage separation of devitalized skin. During this procedure, the

wound and surrounding skin are carefully inspected. The color, odor, size,

exudate, signs of re-epithelialization, andother characteristics of

the wound and the eschar and any changes from the previous dressing change are

noted.

Wound Débridement

As

debris accumulates on the wound surface, it can retard ker-atinocyte migration,

thus delaying the epithelialization process. Débridement, another facet of burn

wound care, has two goals:

·

To remove tissue contaminated

by bacteria and foreign bodies, thereby protecting the patient from invasion of

bacteria

·

To remove devitalized tissue

or burn eschar in preparation for grafting and wound healing

There

are three types of débridement—natural, mechanical, and surgical.

NATURAL DÉBRIDEMENT

With

natural débridement, the dead tissue separates from the un-derlying viable

tissue spontaneously. After partial- and full-thickness burns, bacteria that

are present at the interface of the burned tis-sue and the viable tissue

underneath gradually liquefy the fibrils of collagen that hold the eschar in place for the first or second

postburn week. Proteolytic and other natural enzymes cause this phenomenon.

Using antibacterial topical agents, however, tends to slow this natural process

of eschar separation. It is advanta-geous to the patient to speed this process

through other means, such as mechanical or surgical débridement, thereby

reducing the time during which bacterial invasion and other iatrogenic

prob-lems may arise.

MECHANICAL DÉBRIDEMENT

Mechanical

débridement involves using surgical scissors and for-ceps to separate and

remove the eschar. This technique can be performed by skilled physicians,

nurses, or physical therapists and is usually done with daily dressing changes

and wound cleaning procedures. Débridement by these means is carried out to the

point of pain and bleeding. Hemostatic agents or pressure can be used to stop

bleeding from small vessels.

Dressings

are also useful débriding agents. Coarse-mesh dress-ings applied dry or

wet-to-dry (applied wet and allowed to dry) will slowly débride the wound of

exudate and eschar when they are removed. Topical enzymatic débridement agents

are available to promote débridement of the burn wounds. Because such agents do

not have antimicrobial properties, they should be used with topical

antibacterial therapy to protect the patient from bac-terial invasion.

SURGICAL DÉBRIDEMENT

Early surgical excision to remove devitalized

tissue along with early burn wound closure is now being recognized as one of

the most important factors contributing to survival in a patient with a major

burn injury. Aggressive surgical wound closure has re-duced the incidence of

burn wound sepsis, thus improving sur-vival rates (Gibran & Heimbach,

2000). Early excision is carried out before the natural separation of eschar is

allowed to occur.

Surgical débridement is an operative procedure

involving either primary excision (surgical removal of tissue) of the full

thick-ness of the skin down to the fascia (tangential excision) or shaving the

burned skin layers gradually down to freely bleeding, viable tis-sue. Surgical

excision is initiated early in burn wound manage-ment. This may be performed a

few days after the burn or as soon as the patient is hemodynamically stable and

edema has decreased.

Ideally,

the wound is then covered immediately with a skin graft, if needed, and an

occlusive dressing. If the wound bed is not ready for a skin graft at the time

of excision, a temporary biologic dress-ing may be used until a skin graft can

be applied during subse-quent surgery.

The

use of surgical excision carries with it risks and compli-cations, especially

with large burns. The procedure creates a high risk of extensive blood loss (as

much as 100 to 125 mL of blood per percent body surface excised) and lengthy

operating and anesthesia time. However, when conducted in a timely and

effi-cient manner, surgical excision results in shorter hospital stays and

possibly a decreased risk of complications from invasive burn wound sepsis.

Gerontologic Considerations

Eschar

separation in full-thickness burns is typically delayed in elderly patients,

and older patients are frequently poor risks for surgical excision. Therefore,

prolonged hospitalization, immobi-lization, and associated problems may be

common. If the elderly patient can tolerate surgery, early excision with skin

grafting is the treatment of choice because it decreases the mortality rate in

this population. Prevention of complications of prolonged hos-pitalization,

immobility, and surgery is essential in the care of the elderly burn patient.

Related Topics