Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : Syntax Analysis

Using Ambiguous Grammars

Using Ambiguous Grammars

1 Precedence and Associativity to

Resolve Conflicts

2 The "Dangling-Else"

Ambiguity

3 Error Recovery in LR Parsing

4 Exercises for Section 4.8

It is a fact that every ambiguous grammar fails to be LR and thus is not

in any of the classes of grammars discussed in the previous two sections.

How-ever, certain types of ambiguous grammars are quite useful in the

specification and implementation of languages. For language constructs like

expressions, an ambiguous grammar provides a shorter, more natural

specification than any equivalent unambiguous grammar. Another use of ambiguous

grammars is in isolating commonly occurring syntactic constructs for

special-case optimiza-tion. With an ambiguous grammar, we can specify the

special-case constructs by carefully adding new productions to the grammar.

Although the grammars we use are ambiguous, in all cases we specify

dis-ambiguating rules that allow only one parse tree for each sentence. In this

way, the overall language specification becomes unambiguous, and sometimes it

be-comes possible to design an LR parser that follows the same

ambiguity-resolving choices. We stress that ambiguous constructs should be used

sparingly and in a strictly controlled fashion; otherwise, there can be no

guarantee as to what language is recognized by a parser.

1. Precedence and Associativity

to Resolve Conflicts

Consider the ambiguous grammar ( 4 . 3 ) for expressions with operators

+ and *, repeated here for convenience:

This grammar is ambiguous because it does not specify the associativity

or precedence of the operators + and *. The unambiguous grammar ( 4 . 1 ) ,

which includes productions E -> E + T

and T -> T*F, generates the same

language, but gives + lower precedence than *, and makes both operators left

associative. There are two reasons why we might prefer to use the ambiguous

grammar. First, as we shall see, we can easily change the associativity and

precedence of the operators + and * without disturbing the productions of ( 4 .

3 ) or the number of states in the resulting parser. Second, the parser for the

unam-biguous grammar will spend a substantial fraction of its time reducing by

the productions E -> T and T -> F, whose sole function is to

enforce associativity and precedence. The parser for the ambiguous grammar ( 4

. 3 ) will not waste time reducing by these single

productions (productions whose body consists of a single nonterminal).

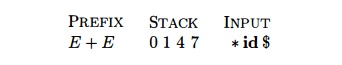

The sets of L R ( 0 ) items for the ambiguous expression grammar ( 4 . 3

) aug-mented by E' -> E are shown

in Fig. 4 . 4 8 . Since grammar ( 4 . 3 ) is ambiguous, there will be

parsing-action conflicts when we try to produce an LR parsing table from the

sets of items. The states corresponding to sets of items Ij and Is generate these

conflicts. Suppose we use the SLR approach to constructing the parsing action

table. The conflict generated by I7 between reduction by E -> E + E and shift

on + or * cannot be resolved, because + and * are each in F O L L O W ( £ ' ) .

Thus both actions would be called for on inputs + and *. A similar conflict is

generated by Is, between reduction by E -> E * E and shift on inputs + and *.

In fact, each of our LR parsing table-construction methods will generate these

conflicts.

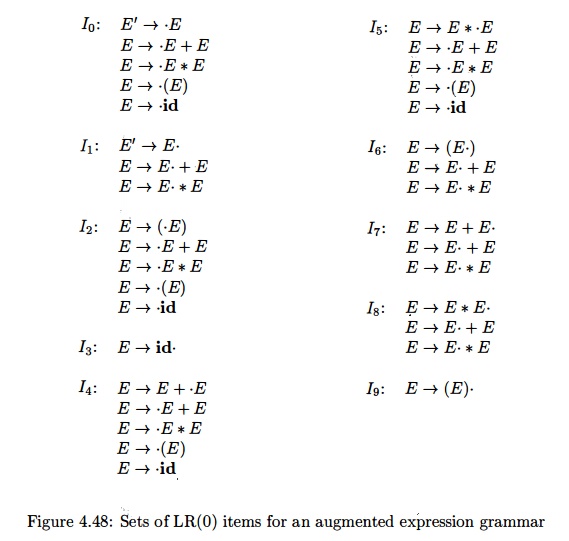

However, these problems can be resolved using the precedence and

associa-tivity information for + and *. Consider the input id + id * id, which

causes a parser based on Fig. 4 . 4 8 to enter state 7 after processing id +

id; in particular the parser reaches a configuration

For convenience, the symbols corresponding to the states 1, 4, and 7 are

also shown under P R E F I X .

If * takes precedence over +, we know the parser should shift * onto the

stack, preparing to reduce the * and its surrounding id symbols to an

expression. This choice was made by the SLR parser of Fig. 4 . 3 7 , based on

an unambiguous grammar for the same language. On the other hand, if + takes

precedence over *, we know the parser should reduce E + E to E. Thus the

relative precedence

Figure 4.48: Sets of LR(0) items

for an augmented expression grammar

of + followed by * uniquely determines how the parsing action conflict

between reducing E -> E + E

and shifting on * in state 7 should be resolved.

If the input had been id + id +

id instead, the parser would still reach a configuration in which it had

stack 0 14 7 after processing input id +

id. On input + there is again a shift/reduce conflict in state 7. Now,

however, the associativity of the + operator determines how this conflict

should be resolved. If + is left associative, the correct action is to reduce

by E —y E + E. That is, the id

symbols surrounding the first + must be grouped first. Again this choice

coincides with what the SLR parser for the unambiguous grammar would do.

In summary, assuming + is left associative, the action of state 7 on

input + should be to reduce by E —> E + E , and assuming that * takes precedence over +, the action of

state 7 on input * should be to shift. Similarly, assuming that * is left

associative and takes precedence over +, we can argue that state 8, which can

appear on top of the stack only when E *

E are the top three grammar symbols, should have the action reduce E ->

E * E on both + and * inputs. In the case of input +, the reason is that *

takes precedence over +, while in the case of input *, the rationale is that *

is left associative.

Proceeding in this way, we obtain the LR parsing table shown in Fig.

4.49. Productions 1 through 4 are E -> E + E, E ->• E * E, ->• (E), and E

-» id, respectively. It is interesting that a similar parsing action table

would be produced by eliminating the reductions by the single productions E -»

T and T —»• F from the SLR table for the unambiguous expression grammar (4.1)

shown in Fig. 4.37. Ambiguous grammars like the one for expressions can be

handled in a similar way in the context of LALR and canonical LR parsing.

2. The "Dangling-Else"

Ambiguity

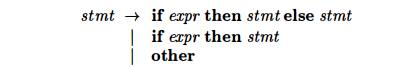

Consider again the following grammar for conditional statements:

As we noted in Section 4.3.2, this grammar is ambiguous because it does

not resolve the dangling-else ambiguity. To simplify the discussion, let us

consider an abstraction of this grammar, where i stands for if expr then, e

stands for else, and a stands for "all other productions." We can then write the grammar, with

augmenting production S' -- > S, as

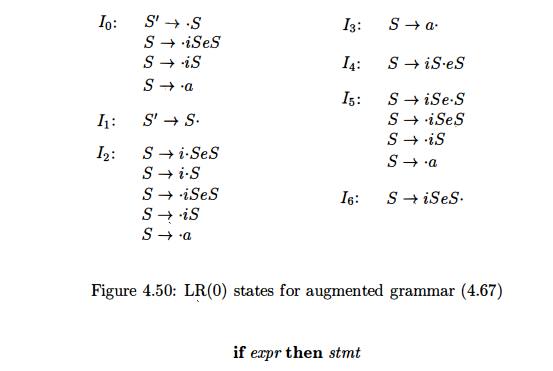

The sets of LR(0) items for grammar (4.67) are shown in Fig. 4.50. The

ambi-guity in (4.67) gives rise to a shift/reduce conflict in I4. There, S

->• iS-eS calls for a shift of e and, since F O L L O W ( 5 ) = {e, $}, item

S ->• iS- calls for reduction by S -> iS on input e.

Translating back to the if-then-else terminology, given

on the stack and else as the first input symbol, should we shift else

onto the stack (i.e., shift e) or reduce if expr t h e n stmt (i.e, reduce by S

—> iS)? The answer is that we should shift else, because it is

"associated" with the previous then . In the terminology of grammar

(4.67), the e on the input, standing for else, can only form part of the body

beginning with the iS now on the top of the stack. If what follows e on the

input cannot be parsed as an 5, completing body iSeS, then it can be shown that

there is no other parse possible.

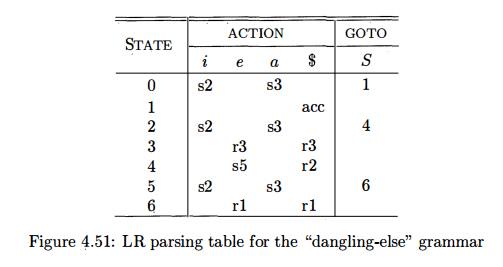

We conclude that the shift/reduce conflict in J4 should be resolved in

favor of shift on input e. The SLR parsing table constructed from the sets of

items of Fig. 4.48, using this resolution of the parsing-action conflict in I4

on input e, is shown in Fig. 4.51. Productions 1 through 3 are S -> iSeS, S

->• iS, and S -)• a, respectively.

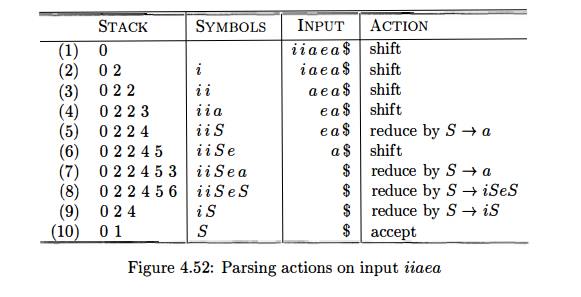

For example, on input iiaea,

the parser makes the moves shown in Fig. 4 . 5 2 , corresponding to the correct

resolution of the "dangling-else." At line ( 5 ) , state 4 selects

the shift action on input e, whereas at line ( 9 ) , state 4 calls for

reduction by S ->• iS on input $.

By way of comparison, if we are unable to use an ambiguous grammar to

specify conditional statements, then we would have to use a bulkier grammar

along the lines of Example 4.16.

3. Error Recovery in LR Parsing

An LR parser will detect an error when it consults the parsing action

table and finds an error entry. Errors are never detected by consulting the

goto table. An LR parser will announce an error as soon as there is no valid

continuation for the portion of the input thus far scanned. A canonical LR

parser will not make even a single reduction before announcing an error. SLR

and LALR parsers may make several reductions before announcing an error, but

they will never shift an erroneous input symbol onto the stack.

In LR parsing, we can implement panic-mode error recovery as follows. We

scan down the stack until a state s with a goto on a particular nonterminal A

is found. Zero or more input symbols are then discarded until a symbol a is

found that can legitimately follow A. The parser then stacks the state GOTO(s,

A) and resumes normal parsing. There might be more than one choice for the

nonterminal A. Normally these would be nonterminals representing major program

pieces, such as an expression, statement, or block. For example, if A is the

nonterminal stmt, a might be semicolon or }, which marks the end of a statement

sequence.

This method of recovery attempts to eliminate the phrase containing the

syntactic error. The parser determines that a string derivable from A contains

an error. Part of that string has already been processed, and the result of

this processing is a sequence of states on top of the stack. The remainder of

the string is still in the input, and the parser attempts to skip over the

remainder of this string by looking for a symbol on the input that can legitimately

follow

By removing states from the

stack, skipping over the input, and pushing GOTO(s, A) on the stack, the parser pretends that it has found an instance

of A and resumes normal parsing.

Phrase-level recovery is implemented by examining each error entry in

the LR parsing table and deciding on the basis of language usage the most

likely programmer error that would give rise to that error. An appropriate

recovery procedure can then be constructed; presumably the top of the stack

and/or first input symbols would be modified in a way deemed appropriate for

each error entry.

In designing specific error-handling routines for an LR parser, we can

fill in each blank entry in the action field with a pointer to an error routine

that will take the appropriate action selected by the compiler designer. The

actions may include insertion or deletion of symbols from the stack or the

input or both, or alteration and transposition of input symbols. We must make

our choices so that the LR parser will not get into an infinite loop. A safe

strategy will assure that at least one input symbol will be removed or shifted

eventually, or that the stack will eventually shrink if the end of the input

has been reached. Popping a stack state that covers a nonterminal should be

avoided, because this modification eliminates from the stack a construct that

has already been successfully parsed.

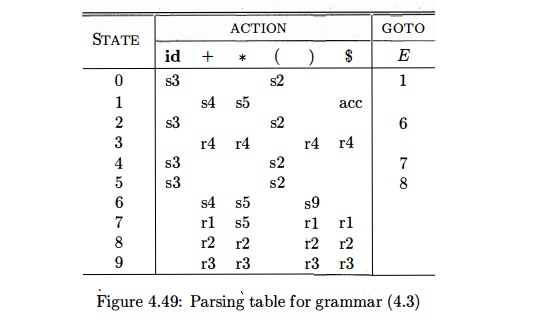

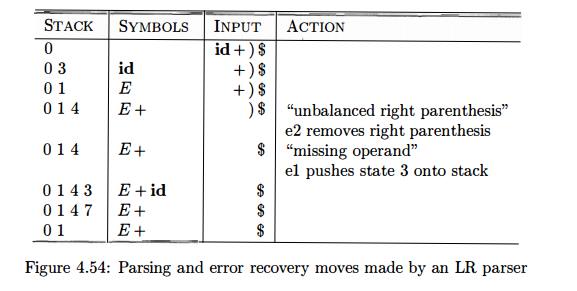

Example 4.68 : Consider again the expression grammar

E -> E + E | E * E | (E) | id

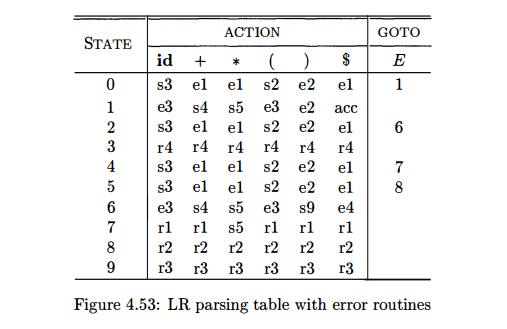

Figure 4.53 shows the LR parsing table from Fig. 4.49 for this grammar,

modified for error detection and recovery. We have changed each state that

calls for a particular reduction on some input symbols by replacing error

entries in that state by the reduction. This change has the effect of

postponing the error detection until one or more reductions are made, but the

error will still be caught before any shift move takes place. The remaining

blank entries from Fig. 4.49 have been replaced by calls to error routines.

The error routines are as follows.

e l : This routine is called from states 0, 2, 4 and 5, all of which

expect the beginning of an operand, either an id or a left parenthesis.

Instead, +, *, or the end of the input was found.

push state 3 (the goto of states 0, 2, 4 and 5 on id); issue diagnostic

"missing operand."

e 2 : Called from states 0, 1, 2, 4 and 5 on finding a right

parenthesis.

remove the right parenthesis from the input; issue diagnostic

"unbalanced right parenthesis."

e3: Called from states 1 or 6 when expecting an operator, and an id or right parenthesis is found.

push state 4 (corresponding to symbol +) onto the stack; issue

diagnostic "missing operator."

e4: Called

from state 6 when the end of the input is found.

push state 9 (for a right parenthesis) onto the stack; issue diagnostic

"missing right parenthesis."

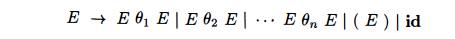

On the erroneous input id + )

, the sequence of configurations entered by the parser is shown in Fig. 4.54. •

4. Exercises for Section 4.8

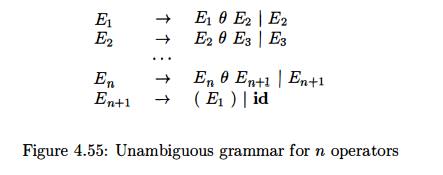

Exercise 4.8.1 : The following is

an ambiguous grammar for expressions with n binary, infix operators, at n

different levels of precedence:

a) As a function of n, what are

the SLR sets of items?

How would you resolve the

conflicts in the SLR items so that all oper-ators are left associative, and 61 takes precedence over 0 2 , which

takes precedence over # 3 , and so on?

Show the SLR parsing table that results from your decisions in part (b).

d) Repeat parts (a) and (c) for the unambiguous grammar, which defines

the same set of expressions, shown in Fig. 4.55.

How do the counts of the number of sets of items and the sizes of the

tables for the two (ambiguous and unambiguous) grammars compare? What does that

comparison tell you about the use of ambiguous expression grammars?

Figure 4.55: Unambiguous grammar for n operators

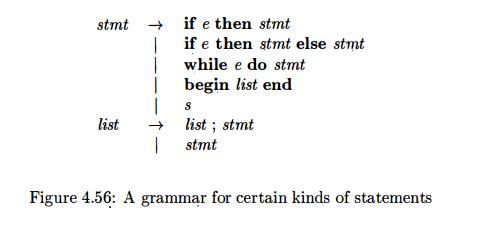

! Exercise 4 . 8 . 2 : In Fig. 4.56 is a grammar for certain statements,

similar to that discussed in Exercise 4.4.12. Again, e and s are terminals

standing for conditional expressions and "other statements,"

respectively.

Build an LR parsing table for

this grammar, resolving conflicts in the usual way for the dangling-else

problem.

Implement error correction by

filling in the blank entries in the parsing table with extra reduce-actions or

suitable error-recovery routines.

Show the behavior of your parser

on the following inputs:

(i) if e then s ; if e then s end

(ii) while e do begin s ; if e then s ; end

Related Topics