Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Upper or Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

Urinary Incontinence - Dysfunctional Voiding Patterns

URINARY

INCONTINENCE

More

than 17 million adults in the United States are estimated to have urinary

incontinence, with most of them experiencing over-active bladder syndrome,

making this disorder more prevalent than diabetes or ulcer disease. Despite

widespread media coverage, urinary incontinence remains underdiagnosed and

underreported. Patients may be too embarrassed to seek help, causing them to

ignore or conceal symptoms. Many patients resort to using ab-sorbent pads or

other devices without having their condition prop-erly diagnosed and treated.

Health care providers must be alert to subtle cues of urinary incontinence and

stay informed about cur-rent management strategies.

The

costs of care for patients with urinary incontinence are not limited to the

dollars spent for absorbent products, medications, and surgical or nonsurgical

treatment modalities. The psycho-social costs of urinary incontinence are also

significant: embar-rassment, loss of self-esteem, and social isolation are

common outcomes. Urinary incontinence in elderly patients often decreases their

ability to maintain an independent lifestyle. This increases dependence on

caregivers and often leads to institutionalization.

Urinary

incontinence affects people of all ages but is particu-larly common among the

elderly. It has been reported that more than half of all nursing home residents

have urinary incontinence. Although urinary incontinence is not a normal

consequence of aging, age-related changes in the urinary tract predispose the

older person to incontinence.

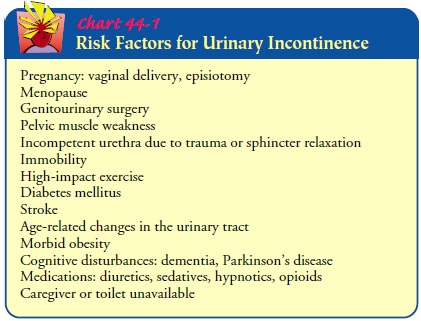

Although

urinary incontinence is commonly regarded as a condition that occurs in older

multiparous women, it is also com-mon in young nulliparous women, especially

during vigorous high-impact activity. Age, gender, and number of vaginal deliv-eries

are established risk factors (Chart 44-1); they explain, in part, the increased

incidence in women. Urinary incontinence is a symptom with many possible

causes.

Clinical Manifestations:Types of Incontinence

Stress incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine through

anintact urethra as a result of a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure

(sneezing, coughing, or changing position). It predomi-nately affects women who

have had vaginal deliveries and is thought to be the result of decreasing

ligament and pelvic floor support of the urethra and decreasing or absent

estrogen levels within the urethral walls and bladder base. In men, stress

incon-tinence is often experienced after a radical prostatectomy for prostate

cancer because of the loss of urethral compression that the prostate had

supplied before the surgery, and possibly blad-der wall irritability (Reilly,

2001; Sueppel et al., 2001) (see Nursing Research Profile 44-1).

Urge incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine

associatedwith a strong urge to void that cannot be suppressed. The patient is

aware of the need to void but is unable to reach a toilet in time. An

uninhibited detrusor contraction is the precipitating factor. This can occur in

a patient with neurologic dysfunction that im-pairs inhibition of bladder

contraction or in a patient without overt neurologic dysfunction (Chancellor,

1999).

Reflex incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine due

tohyperreflexia in the absence of normal sensations usually associated with

voiding. This commonly occurs in patients with spinal cord injury because they

have neither neurologically mediated motor control of the detrusor nor sensory

awareness of the need to void.

Overflow incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine asso-ciated

with overdistention of the bladder. Such overdistention results from the

bladder’s inability to empty normally, despite fre-quent urine loss. Both

neurologic abnormalities (eg, spinal cord lesions) and factors that obstruct

the outflow of urine (eg, tumors, strictures, and prostatic hyperplasia) can

cause overflow inconti-nence (Reilly, 2001).

Functional

incontinence refers to those instances in which lower urinary tract function is

intact but other factors, such as se-vere cognitive impairment (eg, Alzheimer’s

dementia), make it difficult for the patient to identify the need to void or

physical impairments make it difficult or impossible for the patient to reach

the toilet in time for voiding.

Iatrogenic

incontinence refers to the involuntary loss of urine due to extrinsic medical

factors, predominantly medications. One such example is the use of

alpha-adrenergic agents to lower blood pressure. In some individuals with an

intact urinary system, these agents adversely affect the alpha receptors

responsible for bladder neck closing pressure; the bladder neck relaxes to the

point of in-continence with a minimal increase in intra-abdominal pressure,

thus mimicking stress incontinence. As soon as the medication is discontinued,

the apparent incontinence resolves (Reilly, 2001).

Some

patients have several types of urinary incontinence. This mixed incontinence is

usually a combination of stress and urge incontinence.

Only

with appropriate recognition of the problem, assess-ment, and referral for diagnostic

evaluation and treatment can the outcome of incontinence be determined. All

people with incon-tinence should be considered for evaluation and treatment.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Once

incontinence is recognized, a thorough history is necessary. This includes a

detailed description of the problem and a history of medication use. The

patient’s voiding history, a diary of fluid intake and output, and bedside

tests (ie, residual urine, stress

maneuvers) may be used to help determine the type of urinary incontinence

involved. Extensive urodynamic tests may be per-formed;. Urinalysis and urine

culture are per-formed to identify hematuria (from infection, cancer, or a

kidney stone), glycosuria (causes polyuria), pyuria, and bacteriuria (bacteria

in the urine), all of which may identify transient causes of urinary

incontinence.

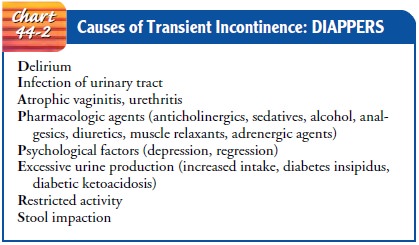

Management

depends on the type of urinary incontinence and its causes. Urinary

incontinence may be transient or re-versible (Chart 44-2), provided that the

underlying cause is suc-cessfully treated and the voiding pattern reverts to

normal. Management of urinary incontinence not considered transient or

reversible falls into three categories: pharmacologic, surgical, and

behavioral.

Gerontologic Considerations

Many

older individuals experience transient episodes of inconti-nence that tend to

be abrupt in onset. When this occurs, the nurse should question the patient, as

well as the family if possi-ble, about the onset of symptoms and any signs or

symptoms of a change in other organ systems.

Acute

urinary tract infection, infection elsewhere in the body, constipation,

decreased fluid intake, a change in a chronic disease pattern, such as elevated

blood glucose levels in patients with di-abetes or decreased estrogen levels in

menopausal women, can provoke the onset of urinary incontinence. If the cause

is identi-fied and modified or eliminated early at the onset of inconti-nence,

the incontinence itself may be eliminated. Although the older bladder is more

vulnerable to unstable detrusor activity, age alone is not a risk factor for

urinary incontinence (Suchinski et al., 1999).

Medical Management

Treatment

of urinary incontinence depends on the underlying cause. Before appropriate

treatment can be initiated, however, the problem and the cause must be

identified.

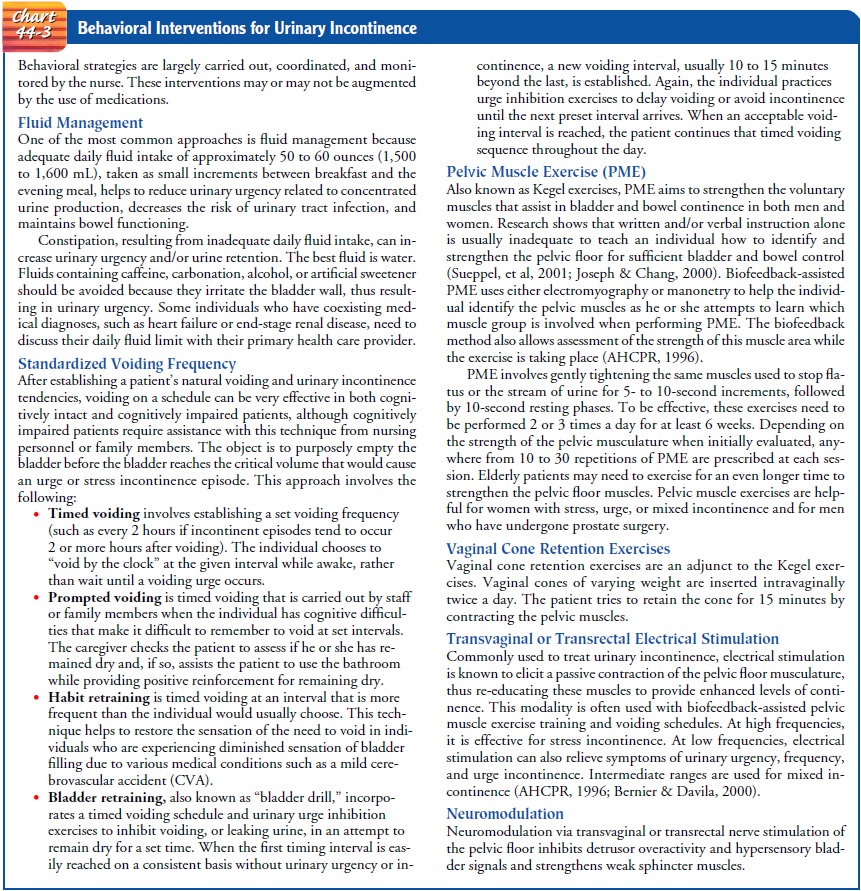

BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Behavioral

therapies are always the first choice to decrease or eliminate urinary

incontinence. In using these techniques, clini-cians help patients avoid

potential adverse effects of pharmaco-logic or surgical interventions (AHCPR,

1996; Roberts, 2001) (Chart 44-3).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Pharmacologic therapy works best when used as an adjunct to behavioral interventions. Anticholinergic agents (oxybutynin [Ditropan],

dicyclomine [Antispas]) inhibit bladder contraction and are considered

first-line medications for urge incontinence. Several tricyclic antidepressant

medications (imipramine, dox-epin, desipramine, and nortriptyline) also

decrease bladder contractions as well as increase bladder neck resistance.

Stress in-continence may be treated using pseudoephedrine (eg, Sudafed).

Estrogen (taken orally, transdermally, or topically) has been shown to be

beneficial for all types of urinary incontinence. Es-trogen decreases

obstruction to urine flow by restoring the mu-cosal, vascular, and muscular

integrity of the urethra.

Gerontologic Considerations

Elderly individuals may experience cognitive decline when taking short-acting anticholinergic medications. The long-acting forms of anticholinergic medications such as oxybutynin (Ditropan XL) and tolterodine (Detrol LA) have a significantly lower inci-dence of adverse effects in all populations, including the elderly (Roberts, 2001).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical

correction may be indicated in patients who have not achieved continence using

behavioral and pharmacologic ther-apy. Surgical options vary according to the

underlying anatomy and the physiologic problem. Most procedures involve lifting

and stabilizing the bladder or urethra to restore the normal urethro-vesical

angle or to lengthen the urethra.

Women

with stress incontinence may have an anterior vagi-nal repair, retropubic

suspension, or needle suspension to reposition the urethra. Procedures to

compress the urethra and increase resistance to urine flow include sling

procedures and placement of periurethral bulking agents such as artificial

collagen.

Periurethral

bulking is a semipermanent procedure in which small amounts of artificial

collagen are placed within the walls of the urethra to enhance the closing

pressure of the urethra. This procedure takes only 10 to 20 minutes and may be

performed under local anesthesia or moderate sedation. A cystoscope is in-serted

into the urethra. An instrument is inserted through the cys-toscope to deliver

a small amount of collagen into the urethral wall at locations selected by the

urologist. The patient is usually discharged home after voiding. There are no

restrictions follow-ing the procedure, although occasionally more than one

collagen bulking session may be necessary if the initial procedure did not halt

the stress urinary incontinence. Collagen placement any-where in the body is

considered semipermanent because its dura-bility averages between 12 and 24

months, until the body absorbs the material. Periurethral bulking with collagen

offers an alterna-tive to surgery, as in a frail, elderly individual. It is

also an option for individuals who are seeking help with stress urinary

inconti-nence who prefer to avoid surgery and who do not have access to

biofeedback and electrical stimulation.

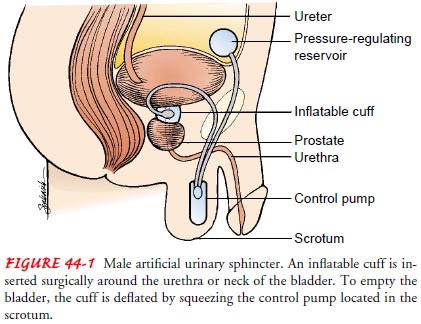

A

modified artificial sphincter that uses a silicone-rubber balloon as a

self-regulating pressure mechanism can be used to close the urethra. Electronic

stimulation of the pelvic floor by means of a miniature pulse generator with

electrodes mounted on an intra-anal plug is another method of controlling

stress in-continence.

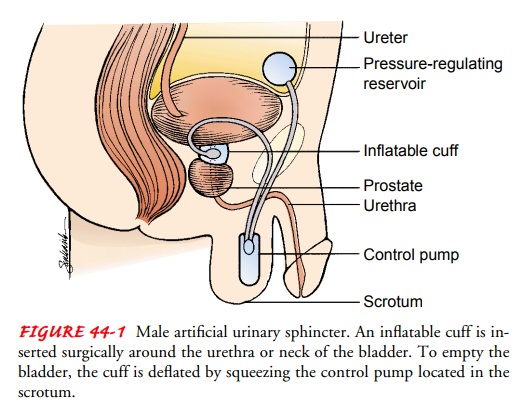

Men

with overflow and stress incontinence may undergo a transurethral resection to

relieve symptoms of prostatic enlarge-ment. An artificial sphincter can be used

after prostatic surgery for sphincter incompetence (Fig. 44-1). After surgery,

peri-urethral bulking agents can be injected into the periurethral area to

increase compression of the urethra.

Nursing Management

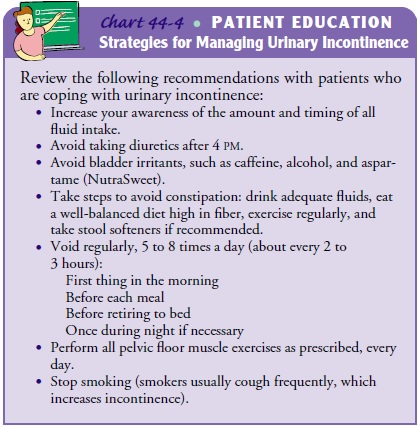

Nursing

management is based on the premise that incontinence is not inevitable with

illness or aging and that it is often reversible and treatable. The nursing

interventions are determined in part by the type of treatment that is

undertaken. For behavioral ther-apy to be effective, the nurse must provide

support and encour-agement, because it is easy for the patient to become

discouraged if therapy does not quickly improve the level of continence.

Pa-tient teaching regarding the bladder program is important and should be

provided verbally and in writing (Chart 44-4). The pa-tient is assisted to

develop and use a log or diary to record timing of Kegel exercises, changes in

bladder function with treatment, and episodes of incontinence.

If pharmacologic treatment is used, its purpose is explained to the patient and family. If surgical correction is undertaken, the procedure and its desired outcomes are described to the patient and family. Follow-up contact with the patient enables the nurse to answer the patient’s questions and to provide reinforcement and encouragement. Patients who have mixed incontinence (both stress and urge incontinence) need to understand that anticholinergic and antispasmodic agents can help decrease urinary urgency and frequency and urge incontinence, but they do not decrease the urinary incontinence related to stress incontinence.

Related Topics