Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Upper or Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

Neurogenic Bladder - Dysfunctional Voiding Patterns

NEUROGENIC

BLADDER

Neurogenic bladder is a dysfunction that results from a lesion

ofthe nervous system. It may be caused by spinal cord injury, spinal tumor,

herniated vertebral disk, multiple sclerosis, congenital anomalies (spina

bifida or myelomeningocele), infection, or dia-betes mellitus.

Pathophysiology

The

two types of neurogenic bladder are spastic (or reflex) blad-der and flaccid

bladder. Spastic bladder is the more common type and is caused by any spinal

cord lesion above the voiding reflex arc (upper motor neuron lesion). The

result is a loss of conscious sensation and cerebral motor control. A spastic

bladder empties on reflex, with minimal or no controlling influence to regulate

its activity.

Flaccid

bladder is caused by a lower motor neuron lesion, commonly resulting from

trauma. This form of neurogenic blad-der has increasingly been recognized as a

problem in patients with diabetes mellitus. The bladder continues to fill and

becomes greatly distended, and overflow incontinence occurs. The blad-der

muscle does not contract forcefully at any time. Because sen-sory loss may accompany

a flaccid bladder, the patient feels no discomfort.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Evaluation

for neurogenic bladder involves measurement of fluid intake, urine output, and

residual urine volume; urinalysis; and assessment of sensory awareness of

bladder fullness and de-gree of motor control. Comprehensive urodynamic studies

are also performed.

Complications

The

most common complication of neurogenic bladder is infec-tion resulting from

urinary stasis and catheterization. Urolithia-sis (stones in the urinary tract)

may develop from urinary stasis, infection, or demineralization of bone from

prolonged immobilization. Renal failure can also occur from vesicoureteral

reflux (backward flow of retained urine from the bladder into the ureters) with

eventual hydronephrosis (dilation of the pelvis of the kidney resulting from

obstruction to the flow of urine) and atrophy of the kidney. Indeed, renal

failure is the major cause of death of pa-tients with neurologic impairment of

the bladder.

Medical Management

The

problems resulting from neurogenic bladder disorders vary considerably from

patient to patient and are a major challenge to the health care team. There are

several long-term objectives ap-propriate for all types of neurogenic bladders:

· Preventing

overdistention of the bladder

· Emptying the bladder

regularly and completely

· Maintaining urine

sterility with no stone formation

· Maintaining adequate

bladder capacity with no reflux

Specific

interventions include continuous, intermittent, or self-catheterization, use of

an ex-ternal condom-type catheter, a diet low in calcium (to prevent calculi),

and encouragement of mobility and ambulation. A lib-eral fluid intake is

encouraged to reduce the urinary bacterial count, reduce stasis, decrease the concentration

of calcium in the urine, and minimize the precipitation of urinary crystals and

sub-sequent stone formation.

To

further enhance bladder emptying of a flaccid bladder, the individual may try

“double voiding.” After each voiding, the in-dividual remains on the toilet,

relaxes for 1 to 2 minutes, and then attempts to void again in an effort to

further empty the bladder. This can be effective in patients with disorders

characterized by neurogenic bladder (eg, multiple sclerosis) (Halper, 1998).

Use of

timed, or habit, voiding is also considered. For exam-ple, a 2-hour voiding

schedule may be established to prevent overdistention. A bladder retraining

program may be effective in treating a spastic bladder or urine retention

(Davies et al., 2000; Joseph, 1999).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Parasympathomimetic

medications, such as bethanechol (Ure-choline), may help to increase the

contraction of the detrusor muscle.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

In

some cases, surgery may be carried out to correct bladder neck contractures or

vesicoureteral reflux or to perform some type of urinary diversion procedure.

CATHETERIZATION

In

patients with a urologic disorder or with marginal kidney func-tion, care must

be taken to ensure that urinary drainage is ade-quate and that kidney function

is preserved. When urine cannot be eliminated naturally and must be drained

artificially, catheters may be inserted directly into the bladder, the ureter,

or the renal pelvis. Catheters vary in size, shape, length, material, and

config-uration. The type of catheter used depends on its

purpose.Catheterization is performed to achieve the following:

· Relieve urinary tract

obstruction

·

Assist with postoperative drainage in urologic and

other surgeries

· Provide a means to

monitor accurate urine output in criti-cally ill patients

· Promote urinary drainage

in patients with neurogenic blad-der dysfunction or urine retention

· Prevent urinary leakage

in patients with stage III to IV pres-sure ulcers

A

patient should be catheterized only if necessary because catheterization

commonly leads to urinary tract infection. In ad-dition, urinary catheters have

been associated with other compli-cations, such as bladder spasms, urethral

strictures, and pressure necrosis.

Indwelling Devices and Infections.

When an indwelling

cath-eter cannot be avoided, a closed drainage system is essential. This

drainage system is designed to prevent any disconnections, thereby reducing the

risk of contamination. One common system consists of an indwelling catheter, a

connecting tube, and a collecting bag with an antireflux chamber emptied by a

drainage spout. Another common system has a triple-lumen indwelling urethral

catheter attached to a closed sterile drainage system. With the triple-lumen

catheter, urinary drainage occurs through one channel. The re-tention balloon

of the catheter is inflated with water or air through the second channel, and

the bladder is continuously irrigated with sterile irrigating solution through

the third channel. Triple-lumen catheters are commonly used after transurethral

prostate surgery.

An

indwelling catheter can lead to infection. Bacterial colo-nization

(bacteriuria) occurs within 2 weeks in half of catheter-ized patients and

within 4 to 6 weeks in almost all patients after insertion of a catheter—even

if recommendations for infection control and catheter care are followed

carefully.

Urinary

tract infections are the most commonly occurring nosocomial infections,

accounting for 40% of them. Every year, about 1 million patients in acute-care

hospitals develop nosoco-mial urinary tract infections, and about 80% of these

are associ-ated with the use of indwelling urinary catheters (Phillips, 2000).

Most urinary tract infections follow instrumentation of the uri-nary tract,

usually catheterization. The pathogens responsible for catheter-associated

urinary tract infections include Escherichiacoli

and Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas,

Enterobacter, Serratia, and Candida

species. Many of these organisms are part of the pa-tient’s endogenous or

normal bowel flora or are acquired through cross-contamination by patients or

health care personnel or through exposure to nonsterile equipment.

Catheters

impede most of the natural defenses of the lower urinary tract by obstructing

the periurethral ducts, irritating the bladder mucosa, and providing an

artificial route for organisms to enter the bladder. Organisms may be

introduced from the ure-thra into the bladder during catheterization, or they

may migrate along the epithelial surface of the urethra or external surface of

the catheter.

The

spout of the urinary drainage bag can become contami-nated when opened to drain

the bag. Bacteria enter the urinary drainage bag, multiply rapidly, and then

migrate to the drainage tubing, catheter, and bladder. Scanning electron

microscopy has demonstrated that thick layers (biofilms) of organisms often

colonize the internal surfaces of catheters and drainage systems (Doyle et al.,

2001; Godfrey & Evans, 2000; Phillips, 2000).

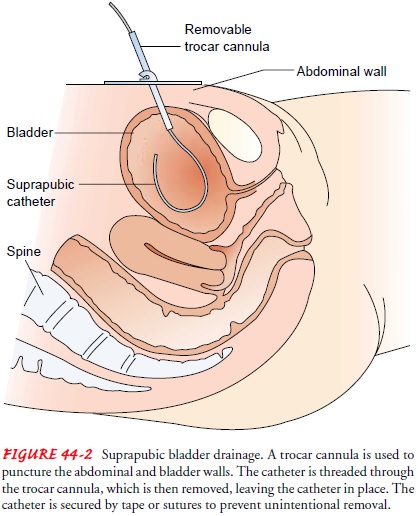

Suprapubic Catheterization.

Suprapubic catheterization allowsbladder drainage by inserting a catheter or tube into the bladder through a suprapubic (above the pubis) incision or puncture (Fig. 44-2).

It may be a temporary measure to divert the flow of urine

from the urethra when the urethral route is impassable (be-cause of injuries,

strictures, prostatic obstruction), after gyneco-logic or other abdominal

surgery when bladder dysfunction is likely to occur, and occasionally after

pelvic fractures. Suprapu-bic catheters may also be used on a long-term basis

for women with urethral destruction secondary to long-term indwelling ure-thral

catheters (Addison, 1999a, 1999b).

For

insertion of the suprapubic catheter, the patient is placed in a supine

position and the bladder distended by administering oral or intravenous fluids

or by instilling sterile saline solution into the bladder through a urethral

catheter. These measures make it easier to locate the bladder. The suprapubic

area is prepared as for surgery and the puncture site located about 5 cm (2 in)

above the symphysis pubis. The bladder is entered through an incision or

through a puncture made by a small trocar (pointed instrument). The catheter or

suprapubic drainage tube is threaded into the blad-der and secured with sutures

or tape; the area around the catheter is covered with a sterile dressing. The

catheter is connected to a sterile closed drainage system, and the tubing is

secured to pre-vent tension on the catheter.

Suprapubic

bladder drainage may be maintained continuously for several weeks. When the

patient’s ability to void is to be tested, the catheter is clamped for 4 hours,

during which time the patient attempts to void. After the patient voids, the

catheter is un-clamped, and the residual urine (the amount of urine remaining)

is measured. If the amount of residual urine is less than 100 mL on two

separate occasions (morning and evening), the catheter is usually removed. If

the patient complains of pain or discomfort, however, the suprapubic catheter

is usually left in place until the patient can void successfully. When a

suprapubic catheter remains in place indefinitely, it is changed regularly at

6- to 12-week in-tervals (Gujral et al., 1999).

Suprapubic

drainage offers certain advantages. Patients can usually void sooner after

surgery than those with urethral cath-eters, and they may be more comfortable.

The catheter allows greater mobility, permits measurement of residual urine

without urethral instrumentation, and presents less risk of bladder infec-tion.

The suprapubic catheter is removed when it is no longer necessary, and a

sterile dressing is placed over the site.

The

patient requires liberal amounts of fluid to prevent en-crustation around the

catheter. Other potential problems include the formation of bladder stones,

acute and chronic infections, and problems collecting urine. An enterostomal

therapist may be con-sulted to assist the patient and family in selecting the

most suitable urine collection system and to teach them about its use and care.

Nursing Management During Catheterization

ASSESSING THE PATIENT AND THE SYSTEM

For

patients with indwelling catheters, the nurse assesses the drainage system to

ensure that it provides adequate urinary drain-age. The color, odor, and volume

of urine are also monitored. An accurate record of fluid intake and urine

output provides essen-tial information about the adequacy of renal function and

urinary drainage.

The

nurse observes the catheter to make sure that it is prop-erly anchored, to

prevent pressure on the urethra at the peno-scrotal junction in male patients,

and to prevent tension and traction on the bladder in both male and female

patients.

Patients

at high risk for urinary tract infection from catheter-ization need to be

identified and monitored carefully. These in-clude women, older adults, and

patients who are debilitated, malnourished, chronically ill, immunosuppressed,

or diabetic. They are observed for signs and symptoms of urinary tract

infec-tion: cloudy malodorous urine, hematuria, fever, chills, anorexia, and

malaise. The area around the urethral orifice is observed for drainage and

excoriation. Urine cultures provide the most accu-rate means of assessing a

patient for infection.

Bladder

ultrasonography can be used for noninvasive mea-surement of bladder volume. A

portable bladder scan can be per-formed to assess the volume of urine in the

bladder, the degree of bladder emptying, and therefore the need for

catheterization (Phillips, 2000; Schott-Baer & Reaume, 2001).

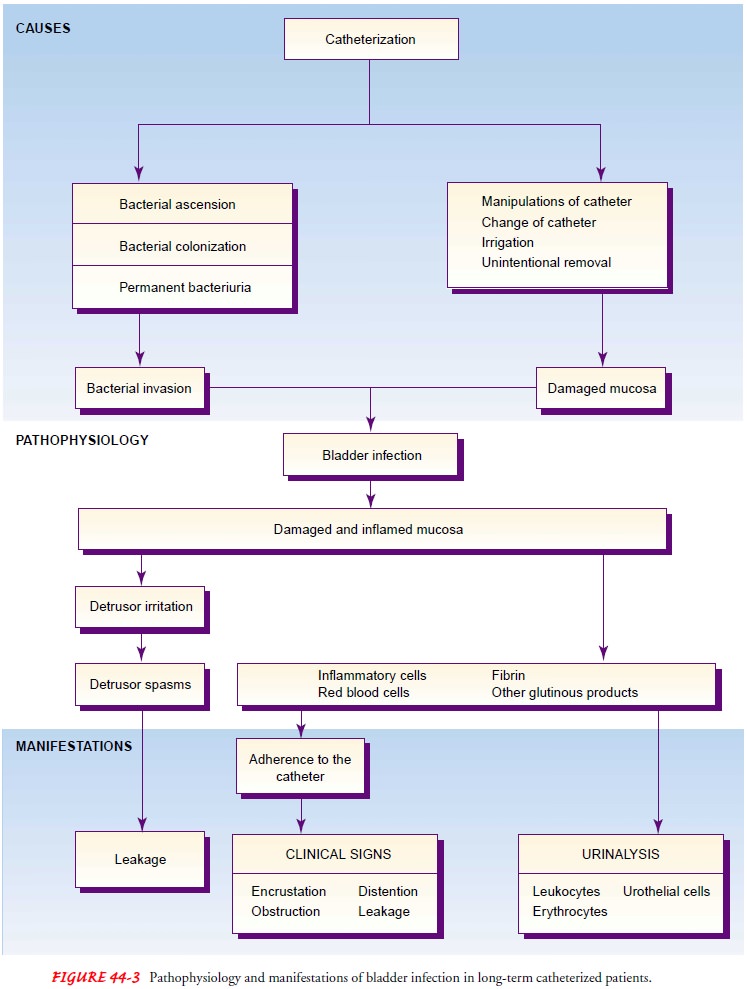

ASSESSING FOR AGE-RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Elderly

patients with an indwelling catheter may not exhibit the typical signs and

symptoms of infection. Therefore, any subtle change in physical condition or

mental status must be considered a possible indication of infection and

promptly investigated because sepsis may occur before the infection is

diagnosed. Figure 44-3 summarizes the sequence of events leading to infection

and leak-age of urine that often follow long-term use of an indwelling catheter

in elderly patients.

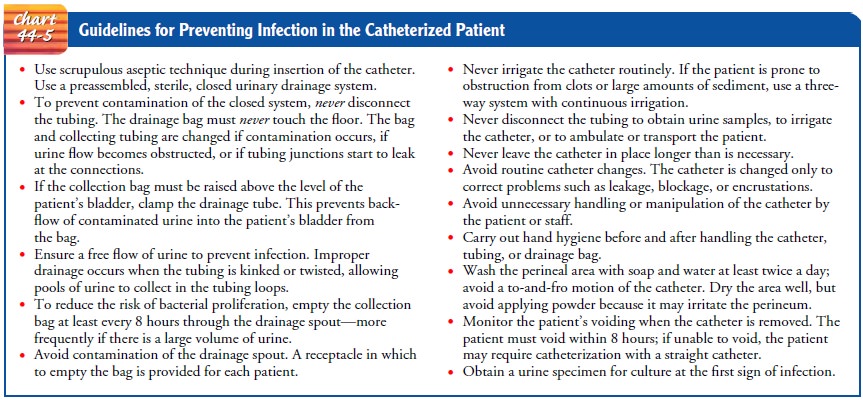

PREVENTING INFECTION

Certain

principles of care are essential to prevent infection in pa-tients with a

closed urinary drainage system (Chart 44-5). The catheter is a foreign body in

the urethra and produces a reaction in the urethral mucosa with some urethral

discharge. Vigorous cleaning of the meatus while the catheter is in place is

discour-aged, however, because the cleaning action can move the catheter to and

fro, increasing the risk of infection. To remove obvious en-crustations from

the external catheter surface, the area can be washed gently with soap during

the daily bath. The catheter is an-chored as securely as possible to prevent it

from moving in the urethra. Encrustations arising from urinary salts may serve

as a nucleus for stone formation; however, using silicone catheters results in

significantly less crust formation.

A

liberal fluid intake, within the limits of the patient’s cardiac and renal

reserve, and an increased urine output must be ensured to flush the catheter

and to dilute urinary substances that might form encrustations.

Urine

cultures are obtained as prescribed or indicated in mon-itoring the patient for

infection; many catheters have an aspiration (puncture) port from which a

specimen can be obtained.

Controversy

exists about the usefulness of taking cultures and treating bacteriuria in

patients who have symptoms of infection and who have indwelling catheters.

Bacteriuria is considered to be inevitable, and overtreatment may lead to

resistant strains of bacteria (Suchinski et al., 1999).

MINIMIZING TRAUMA

Trauma

to the urethra can be minimized by:

· Using an

appropriate-sized catheter

· Lubricating the catheter

adequately with a water-soluble lu-bricant during insertion

· Inserting the catheter

far enough into the bladder to prevent trauma to the urethral tissues when the

retention balloon of the catheter is inflated

Manipulation

of the catheter is the most common cause of trauma to the bladder mucosa in the

catheterized patient. In-fection then inevitably occurs when urine invades the

damaged mucosa.

The

catheter is secured properly to prevent it from moving, causing traction on the

urethra, or being unintentionally re-moved, and care is taken to ensure that

the catheter position per-mits leg movement. In male patients, the drainage

tube (not the catheter) is taped laterally to the thigh to prevent pressure on

the urethra at the penoscrotal junction, which can eventually lead to formation

of a urethrocutaneous fistula. In female patients, the drainage tubing attached

to the catheter is taped to the thigh to prevent tension and traction on the

bladder.

Care

is taken to ensure that any patient who is confused does not remove the

catheter with the retention balloon still inflated. This could cause bleeding

and considerable injury to the urethra (Phillips, 2000).

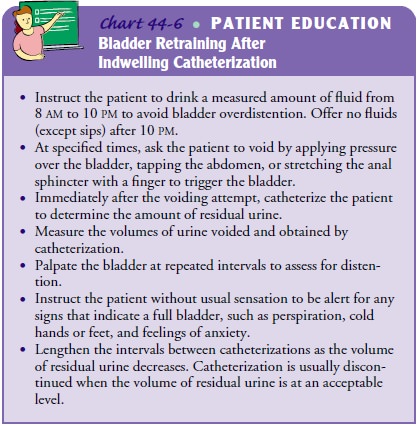

RETRAINING THE BLADDER

When

an indwelling urinary catheter is in place, the detrusor muscle does not

actively contract the bladder wall to stimulate emptying, because urine is

continuously draining from the blad-der. As a result, the detrusor may not

immediately respond to bladder filling when the catheter is removed, resulting

in either urine retention or urinary incontinence. This condition, known as

postcatheterization detrusor instability, can be managed with bladder

retraining (Chart 44-6).

Immediately after the indwelling catheter is removed, the pa-tient is placed on a timed voiding schedule, usually every 2 to 3 hours. At the given time interval, the patient is instructed to void. The bladder is then scanned using a portable ultrasonic blad-der scanner. If 100 mL or more of urine remains in the bladder, straight catheterization may be performed for complete bladder emptying.

After a few days, as the nerve endings in the bladder wall become aware of

bladder filling and emptying, bladder func-tion usually returns to normal. If

the individual has had an in-dwelling catheter in place for an extended period,

bladder retraining will take much longer; in some cases, function may never

return to normal. If this occurs, long-term intermittent catheterization may

become necessary (Phillips, 2000).

ASSISTING WITH INTERMITTENT SELF-CATHETERIZATION

Intermittent self-catheterization provides periodic drainage of urine from the bladder. By promoting drainage and eliminating excessive residual urine, intermittent catheterization protects the kidneys, reduces the incidence of urinary tract infections, and improves continence.

It is the treatment of choice in patients with spinal cord injury

and other neurologic disorders, such as multi-ple sclerosis, when the ability

to empty the bladder is impaired. Self-catheterization promotes independence,

results in few com-plications, and enhances self-esteem and quality of life.

When

teaching the patient how to perform self-catheterization, the nurse must use

aseptic technique to minimize the risk of cross-contamination. The patient,

however, may use a “clean” (non-sterile) technique at home, where the risk of

cross-contamination is reduced. Either antibacterial liquid soap or

povidone-iodine (Betadine) solution is recommended for cleaning urinary

cath-eters at home. The catheter is thoroughly rinsed with tap water after

soaking in the cleaning solution. It must dry before reuse. It should be kept

in its own container, such as a plastic food-storage bag.

In

teaching the patient, the nurse emphasizes the importance of frequent

catheterization and emptying the bladder at the pre-scribed time. The average

daytime clean intermittent catheteri-zation schedule is every 4 to 6 hours and

just before bedtime. If the patient is awakened at night with an urge to void,

catheteri-zation may be performed after an attempt to void (Reilly, 2001).

The

female patient assumes a Fowler’s position and uses a mirror to help locate the

urinary meatus. She inserts the catheter 7.5 cm (3 in) into the urethra, in a

downward and backward di-rection. The male patient assumes a Fowler’s or

sitting position, lubricates the catheter and retracts the foreskin of the

penis with one hand while grasping the penis and holding it at a right angle to

the body. (This maneuver straightens the urethra and makes it easier to insert

the catheter.) He inserts the catheter 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 in) until urine

begins to flow. After removal, the catheter is cleaned, rinsed, and wrapped in

a paper towel or placed in a plastic bag or case. Patients following this

routine should consult a primary health care provider at regular intervals to

assess urinary function and to detect complications.

If the

patient cannot perform intermittent self-catheterization, a family member may

be taught to carry out the procedure at reg-ular intervals during the day.

Another

self-catheterization option is creation of the Mitro-fanoff umbilical appendicovesicostomy,

which provides easy access to the bladder. In this procedure, the bladder neck

is closed and the appendix is used to gain access to the bladder from the skin

surface. A submucosal tunnel is created with the appendix; one end of the

appendix is brought to the skin surface and used as a stoma and the other end

is tunneled into the bladder. The ap-pendix may be used as an artificial

urinary sphincter when an alter-native is necessary to empty the bladder. In

children, the most common reason for the procedure is spina bifida. In adults,

a sur-gically prepared continent urine reservoir with a sphincter mecha-nism is

required in cases of bladder cancer, severe interstitial cystitis, or in males,

bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex when a radical cystectomy (surgical

removal of the bladder) is necessary. This pro-cedure for surgically creating a

sphincter, which is attached to an internal pouch reservoir that can be

catheterized, is possible only in individuals who have a healthy appendix

(Kajbafzadeh & Chubak, 2001; Uygur et al., 2001).

Related Topics