Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Upper or Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

Continuous Renal Replacement Therapies - Dialysis

CONTINUOUS

RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPIES

Several

types of continuous renal replacement

therapy (CRRT) are available and are widely used in critical care units.

CRRT may be indicated for patients who have acute or chronic renal failure and

who are too clinically unstable for traditional hemodialysis, for patients with

fluid overload secondary to oliguric (low urine output) renal failure, and for

patients whose kidneys cannot han-dle their acutely high metabolic or

nutritional needs. CRRT does not produce rapid fluid shifts, does not require

dialysis machines or dialysis personnel to carry out the procedures, and can be

ini-tiated quickly in hospitals without dialysis facilities.

CRRT

methods are similar to hemodialysis methods in that they require access to the

circulation and blood to pass through an artificial filter. A hemofilter (an

extremely porous blood filter containing a semipermeable membrane) is used in

all CRRT methods, which are described below (Astle, 2001).

Continuous Arteriovenous Hemofiltration

Continuous arteriovenous hemofiltration (CAVH) was firstused in 1977 to

treat fluid overload. Blood is circulated through a small-volume,

low-resistance filter, using the patient’s arterial pressure rather than that

of the blood pump as is used in he-modialysis. Blood flows from an artery

(usually by an arterial catheter in the femoral artery) to a hemofilter. A

pressure gradi-ent is necessary for optimal filtration; cannulation of the

femoral artery and vein provides the necessary gradient (difference) in

ar-terial and venous pressures. The filtered blood then returns to the

patient’s circulation through a venous catheter. Intravenous flu-ids may be

administered to replace fluid removed by the proce-dure. With CAVH, there is no

concentration gradient, so only fluid is filtered. Electrolytes are eliminated

only as they are pulled along and removed with the fluid. Ultrafiltrate is

collected in a drainage bag, measured, and discarded. CAVH is usually set up

and initiated by trained dialysis staff and then maintained and monitored by

critical care personnel.

Continuous Arteriovenous Hemodialysis

Continuous arteriovenous hemodialysis (CAVHD) has manyof the

characteristics of CAVH but offers the advantage of a concentration gradient

for faster clearance of urea. This is ac-complished by the circulation of

dialysate on one side of a semi-permeable membrane. The blood flow through the

system depends on the patient’s arterial pressure, as in CAVH; a blood pump is

not used as it is in standard hemodialysis. CAVHD is usually set up and

initiated by trained dialysis staff and then maintained and monitored by

critical care personnel.

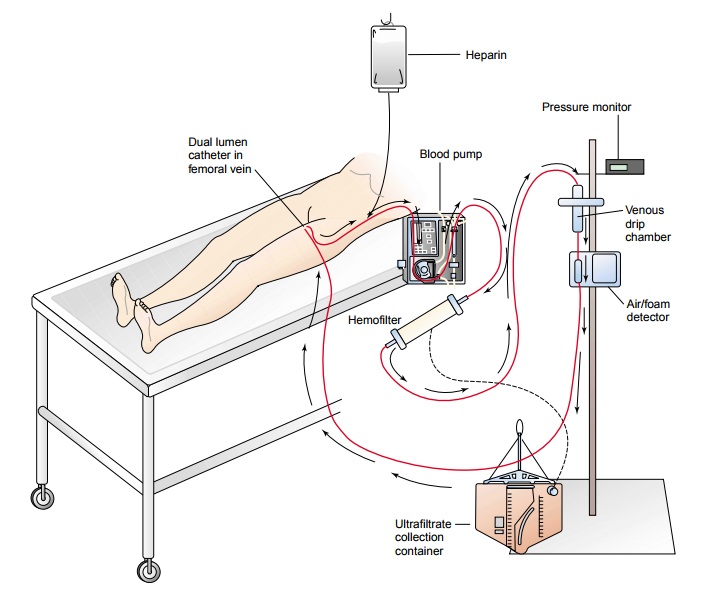

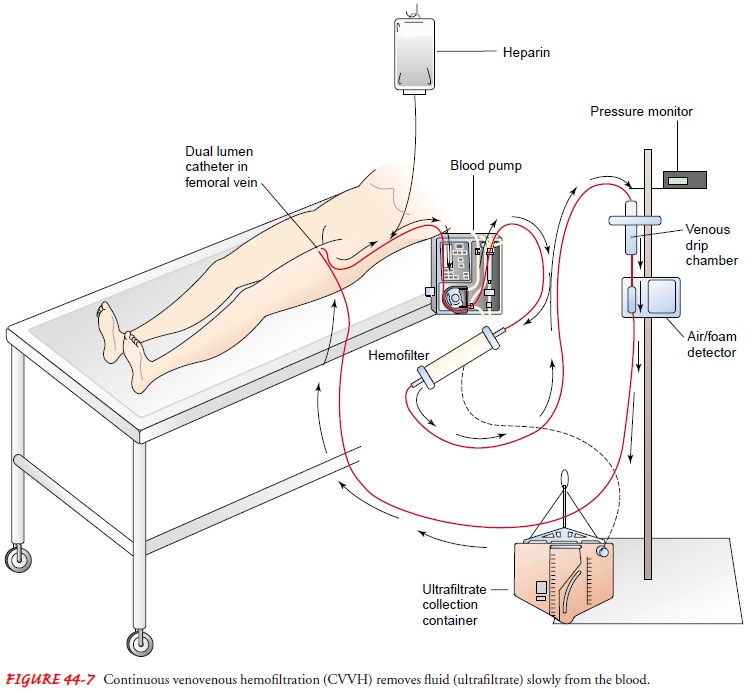

Continuous Venovenous Hemofiltration

Continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) is increas-ingly being

used in managing acute renal failure. Blood from a double-lumen venous catheter

is pumped (using a small blood pump) through a hemofilter and then returned to

the patient through the same catheter (Fig. 44-7). CVVH provides continu-ous

slow fluid removal (ultrafiltration); therefore, hemodynamic effects are mild

and better tolerated by patients with unstable conditions. CVVH has several

other benefits over CAVH in that no arterial access is required and critical

care nurses can set up, initiate, maintain, and terminate the system.

Continuous Venovenous Hemodialysis

Continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD) is similar toCVVH. Blood

is pumped from a double-lumen venous catheter through a hemofilter and returned

to the patient through the same catheter. In addition to the benefits of

ultrafiltration, CVVHD uses a concentration gradient to facilitate the removal

of uremic toxins. Therefore, no arterial access is required, hemodynamic

effects are usually mild, and critical care nurses can set up, ini-tiate,

maintain, and terminate the system.

Related Topics