Chapter: Basic Radiology : Radiology of the Urinary Tract

Ultrasonography - Radiology of the Urinary Tract: Techniques and Normal Anatomy

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound is a useful technique

for evaluation of the urinary tract, with its principal advantages including

wide availabil-ity, no need for intravenous contrast material, and lack of

ionizing radiation. The kidneys are generally well seen by a posterior or

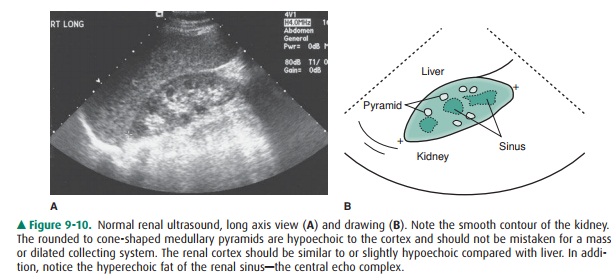

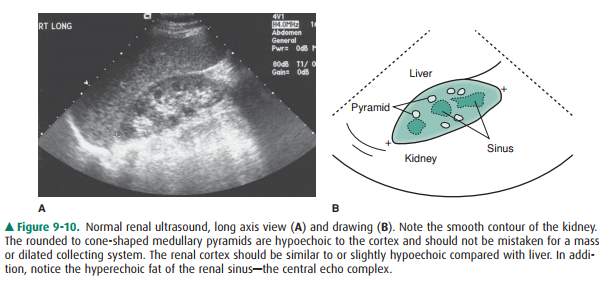

lateral approach in all but the largest of patients (Figure 9-10). The renal

medulla is hypoechoic (darker) rela-tive to renal cortex and can be identified

in some adults as cone-shaped central structures. In some patients, this

corti-comedullary distinction is not visible and should not be con-sidered

pathologic. The renal cortex is isoechoic or slightly hypoechoic compared with

the echogenicity of the adjacent liver. Renal echogenicity exceeding that of

the liver is abnor-mal and requires explanation. Most commonly, hyperechoic

kidneys are the result of medical renal disease, such as end-stage hypertensive

glomerulosclerosis. In addition to echogenicity and as with CT evaluation, the

kidneys should be assessed for size, location, and symmetry. Scarring and

masses can be evaluated. US assessment is often specific in identifying sim-ple

or mildly complicated cysts and differentiating these lesions from a solid

mass. Solid masses, however, remain nonspecific and generally require further

evaluation. There are normal variants that can mimic mass lesions, including

dromedary humps, as well as central prominences of normal renal tissue

interposed between lobes referred to as persistent columns of Bertin.

Additionally, the parenchyma near the renal hila may appear prominent as well,

occasionally mim-icking a mass. Each of these variants may be distinguished by

its normal echogenicity, lack of mass effect, and characteris-tic location.

Occasionally, additional imaging with CT or MR may be required in equivocal

masses. The renal sinus is the area engulfed by the kidney medially, harboring

the renal pelvis, arteries, veins, nerves, and lymphatics that enter and exit

the kidney, all contained within a variable amount of fat. Fat is typically

brightly echogenic on ultrasound, and fat within the renal sinus dominates the

ultrasonographic appear-ance, creating what is known as the “central echo

complex.” The size of the central echo complex is variable, often more

prominent in the elderly and minimal in the child. Absence of the central echo

complex may suggest a mass such as a urothelial carcinoma replacing the normal

fat. Alternatively, the complex may be very prominent in the benign condition

of renal sinus lipomatosis. Calcifications often have a typical appearance on

ultrasound, being brightly echogenic and re-sulting in shadowing posteriorly as

the sound waves are at-tenuated. Renal stones or calcifications may be detected

within the renal parenchyma or in the intrarenal collecting system. The

echogenicity of the normal renal sinus, however, may be problematic by

obscuring or mimicking small stones. Ultrasound is also excellent for detecting

hydronephrosis, with the distended collecting system easily recognized within

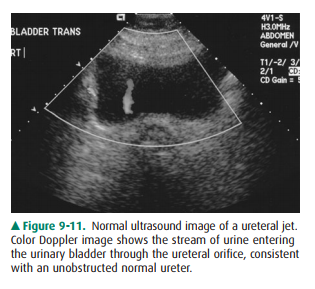

the central echo complex. The ureters are not normally seen on ultrasound

because of obscuring overlying tissue and their small size. Evidence of their

patency may be verified by Doppler detection of urine rapidly entering the

bladder from the distal ureters that is, distal ureteral jets (Figure 9-11).

The bladder is seen as a rounded or oval anechoic (fluid) structure in the

pelvis. The bladder may demonstrate mass lesions, such as transitional-cell

carcinoma, or stones. The urethra is not typically seen by ultrasound, although

urethral diverticula may occasionally be demonstrated.

Related Topics