Chapter: Basic Radiology : Radiology of the Urinary Tract

Exercise: Hematuria

EXERCISE 9-4.

HEMATURIA

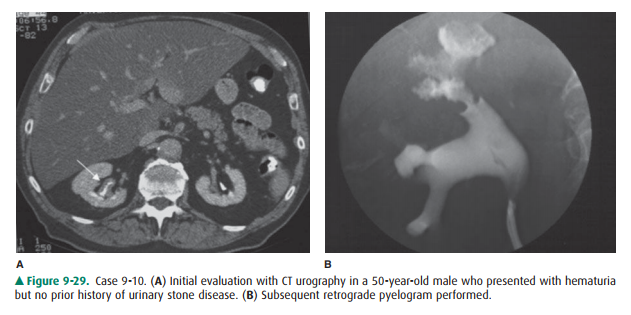

9-10. Based on the two

images from Case 9-10 (Figure 9-29), what is the most likely diagnosis?

A.

Squamous cell carcinoma

B.

Renal stone

C.

Urothelial cell carcinoma

D.

Blood clot

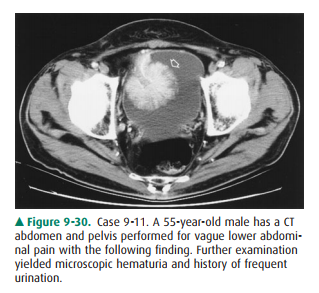

9-11. What would be the

recommended next step in the evaluation and management of the lesion in Case

9-11 (Figure 9-30)?

A.

Cystoscopy

B.

Retrograde cystogram

C.

PET/CT

D.

MRI

Radiographic Findings

In Case 9-10, the first image

from the excretory phase of a CT urogram (Figure 9-29 A) shows thickening of

the mucosal surface (arrow) of the right renal pelvis, compared to the

con-tralateral kidney where the wall is imperceptibly thin. On the retrograde

pyelogram (Figure 9-29B), the upper pole calyces are irregular in contour,

having a “moth-eaten” appearance.

Blood clots are typically

intraluminal filling defects (D is incorrect). Although squamous cell carcinoma

is a differen-tial consideration, this is much less common than urothelial cell

carcinoma. Additionally, clots often are associated with calcifications and

recurrent infections (A is incorrect). This lesion is highly suggestive of

urothelial cell carcinoma, the most common malignancy of the urinary collecting

tract and bladder (C is the correct answer to Question 9-10). Therefore,

further urologic evaluation with cystoscopy and ureteroscopy is recommended.

Regarding the patient in Case

9-11, the image taken from a CT scan (Figure 9-30) of the pelvis shows an

en-hancing, pedunculated mass (arrow) arising from the ante-rior wall of the

urinary bladder. A retrograde cystogram would effectively demonstrate the

presence of a bladder mass, but would do little to narrow the differential (B

is in-correct). PET/CT can prove useful for the detection of metastatic

disease, but is of limited use for evaluating a pri-mary uroepithelial neoplasm

because of the presence of FDG in the excreted urine, which can mask lesion

uptake (C is incorrect). MRI is coming into use to establish depth of invasion

into the bladder wall, but this would be at the dis-cretion of the surgical

oncologist following the establish-ment of a diagnosis. The gold standard for

evaluation of a known bladder mass is cystoscopy (A is the correct answer to

Question 9-11), which allows direct visualization and biopsy for a definitive

diagnosis.

Discussion

Urothelial cell carcinoma

(formally known as transitional cell carcinoma or TCC) is the most common

neoplasm of the urinary tract, and up to 90% of all neoplasms of the bladder

itself. Although TCCs can occur anywhere that there is tran-sitional

epithelium, from the renal collecting system to the urethra, they are most

commonly found in the urinary blad-der. This is felt to be due to several

factors, including the large surface area of the bladder. Also, because the

bladder acts as a temporary storage site prior to excretion, carcinogens remain

in contact with the epithelium of the bladder for a longer period of time than

they do with that of the remainder of the urinary tract. TCC is associated with

numerous chemical car-cinogens as well as cigarette smoking. Bladder urothelial

cell carcinoma usually initially presents with hematuria, which is most

commonly microscopic. A TCC can obstruct the vesi-coureteral junction and cause

obstructive symptoms as well. TCC of the bladder spreads by local invasion and

by lym-phatic and hematogenous spread. Most TCCs are superficial at

presentation, with only about 1 in 4 displaying muscle in-vasion and 1 in 20

having distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.

Plain films are most often

unremarkable in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, with less than 1%

displaying some stippled calcifications. TCCs can be seen as filling defects in

a contrast-filled bladder, particularly when greater than 1 cm in size. Filling

defects within the bladder on cystography are somewhat nonspecific, with

considerations including tumor, radiolucent stones, fungus balls, and blood

clots. However, transitional cell cancers have a characteristic stippled and

frondlike appearance. Ultrasound can show ex-ophytic soft-tissue lesion within

the bladder. CT urography is the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of

possible bladder masses, because the size of the mass itself, as well as the

extent of invasion through the bladder wall into adjacent pelvic structures,

can be evaluated. The use of urographic phase imaging and reformats allows the

detection of even small, sessile lesions in the bladder, ureters, or renal

pelvis. CT also allows evaluation of abdominal and pelvic lymph nodes and

posttreatment examination for tumor recurrence. MRI can assess depth of bladder

tumor invasion, but is not currently routinely used in tumor staging. Although

the foregoing imaging findings strongly suggest the diagnosis of TCC,

cystoscopy is important to confirm the histologic di-agnosis. Cystoscopy is

also indicated when CT urography does not demonstrate a source for hematuria.

Other less common tumors of the bladder include malignancies such as squamous

cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, uncom-mon benign lesions, and some masslike

manifestations of inflammatory processes.

Related Topics