Chapter: Basic Radiology : Radiology of the Urinary Tract

Exercise: Stone Disease

EXERCISE 9-3.

STONE DISEASE

9-8. What is the most likely diagnosis for the patient in Case 9-8 (Figure 9-25)?

A.

Acute appendicitis

B.

Right ureteral calculus

C.

Ruptured aortic aneurysm

D.

Pelvic phlebolith

9-9. What is the most

likely diagnosis for the patient in Case 9-9 (Figure 9-26)?

A.

Medullary nephrocalcinosis

B.

Cortical nephrocalcinosis

C.

Renal tuberculosis

D.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis

Radiographic Findings

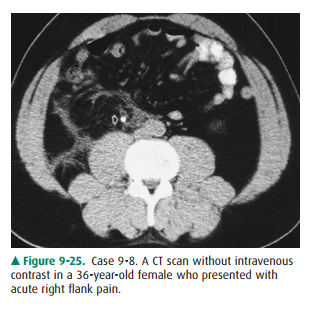

Case 9-8 (Figure 9-25) is a CT

scan of the abdomen obtained without intravenous contrast. Stranding in the fat

planes can be seen on the right in the retroperitoneum. Stranding within the

fat planes on a CT is a nonspecific finding resulting from many conditions. In

general, the stranding can be related to inflammation such as recent surgery,

infection, or abnormal fluid collections such as blood or urine. Thus, the

stranding seen in this case could result from any of the three listed pos-sible

answers. However, within the right ureter is a high-density rounded structure

(arrow) consistent with a ureteral calculus (B is the correct answer to

Question 9-8). Two main parame ters that should be noted are the size and

location of a stone, as these two factors are directly related to the

likelihood of stone passage. Additionally, once the diagnosis of a ureteral

stone is made, the radiologist must continue to evaluate the remainder of the

scan, because additional abnormalities may also exist.

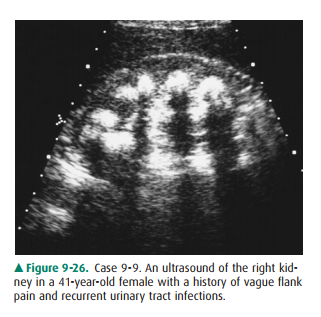

In Case 9-9, a renal ultrasound (Figure 9-26) demon-strates rounded highly echogenic areas throughout the central parenchyma of the kidney. Several important additional obser-vations include strong uniform shadowing posteriorly from the echogenic areas consistent with sound attenuation and suggesting calcification. Although attenuation of the ultra-sound beam occurs with air, such as might occur with emphy-sematous pyelonephritis, the shadowing in those cases is often “dirty” in appearance, being somewhat inhomogeneous (D is incorrect). Also, the calcifications are located in the medullary area of the kidney, unlike the cortical location of cortical nephrocalcinosis (A is correct answer to Question 9-9).

Discussion

Suspected stone disease is a

common indication for urinary tract imaging. Calcifications occurring in the

kidney can be dystrophic, related to abnormal tissue such as within tumors,

cysts, or infection. This type of calcification is to be distin-guished from

nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis. Nephro-calcinosis refers to the

development of calcification within the renal parenchyma, generally unrelated

to an underlying renal pathology. Furthermore, nephrocalcinosis should be

distinguished from nephrolithiasis, in which there are stones within the

collecting system. Note that nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis may coexist.

Nephrocalcinosis is additionally

subdivided into two cat-egories depending on location. That which occurs in the

renal cortex is termed cortical nephrocalcinosis, and that within the medulla

is called medullary nephrocalcinosis. Cortical nephrocalcinosis is less common

and occurs most frequently in the setting of chronic glomerulonephritis or

acute cortical necrosis. Acute cortical necrosis most often oc-curs in the

setting of hypotensive shock or toxic ingestion. Cortical nephrocalcinosis may

be detected on plain radi-ographs or cross-sectional imaging modalities such as

CT or US. The diagnosis is usually made by demonstrating thin lin-ear bands of

calcification at the extreme periphery of the kid-ney that may extend into the

columns of Bertin but should not involve the renal medulla. Medullary

nephrocalcinosis is more frequently observed than cortical disease and is most

often due to hypercalcemic states such as hyperparathy-roidism, renal tubular

acidosis, or medullary sponge kidney. On plain films and CT studies, medullary

nephrocalcinosis appears as speckled or dense calcifications within the renal

medulla, sparing the cortex. In medullary sponge kidney, an anatomic condition

of abnormally dilated collecting tubules, the condition may be unilateral or

even focal, although medullary nephrocalcinosis from other causes is typically

bi-lateral and diffuse. On ultrasound, shadowing echogenic foci are noted

within the renal medulla.

Nephrolithiasis (better known as

“kidney stones”) is much more common than nephrocalcinosis. In fact, urinary

tract calculi occur in as many as 12% of the population of the United States.

Although there are clearly definable causes in some cases (hereditary

conditions, metabolic diseases such as gout, certain urinary tract infections,

and predisposing anatomic conditions), the vast majority of patients have

idiopathic stone disease. Many small stones that are located within the

intrarenal collecting system are asymptomatic; however, stones that pass into

the ureter (ureterolithiasis) may obstruct the urinary tract and result in

excruciating pain. Additionally, stones may cause hematuria or be a nidus for

recurrent infection. Conventional radiographs have long been used to evaluate

stone disease; in fact, the first descrip-tion of urinary calculi was in April

1896, only a few months after the discovery of the x-ray by Roentgen. Stones

appear as calcific densities on x-rays overlying the urinary tract (Figure

9-27). Urinary tract calculi are variably opaque and visible depending on their

size, composition, and location. The ac-curacy of conventional radiographs for

detecting stones has long been overestimated. Perhaps only 50% of stones are

identified prospectively, and one can never be certain that an individual

calcification on an isolated plain radiograph is within the urinary tract or

simply overlies it. Confusing calci-fications are many, including phleboliths,

arterial calcifica-tions, calcified lymph nodes, and other calcified masses.

Stones on ultrasound appear as brightly echogenic structures and often with

posterior shadowing. However, not all stones shadow, and as there are many

small noncalcific echogenicfoci (vessels, fat) normally within the kidney, the

accuracy for detecting renal calculi is only moderate with ultrasound.

Additionally, ultrasound suffers from its ability to visualize only the most

proximal and distal ureters and must rely on nonspecific indirect signs such as

hydronephrosis and absent ureteral jets to suggest ureteral stones and

obstruction. CT is now the imaging examination of choice for evaluation of

renal stone disease. Virtually all urinary tract stones are dense on CT and

show up as bright foci. Even stones as small as 1 mm are visible with modern

scanners. Additionally, the en-tire urinary tract can be visualized on CT

without overlap-ping or obscuring structures. In patients who present acutely

with flank pain and are suspected of having ureteral stones, CT has become the

study of choice. The diagnosis is con-firmed by directly identifying a stone

within the ureter. Sec-ondary findings of obstructing may also be identified on

CT, helping to confirm the diagnosis. Renal enlargement, perinephric stranding,

and dilation of the ureter and in-trarenal collecting system are frequently

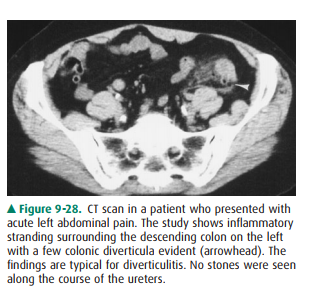

present in ureteral obstruction. One major additional advantage to CT is the

ability to identify alternative explanations for the cause of a patient’s acute

flank pain. In fact, as many as one-third of all patients originally felt to

have ureteral stones are shown byCT to have an alternative diagnosis (Figure

9-28). At this point, MRI performs little role in the evaluation of stone

disease.

In pregnant patients with

suspected obstructing calculi, CT is not contraindicated. By using a low-dose

CT technique with lowered tube current and increased pitch, fetal dose can be

lowered to as little as 3 mGy. This is well below the thresh-old for fetal

anomalies of 50 mGy, and below the threshold for increased risk of childhood

malignancy of 10 mGy. A sim-ilar technique can also be used in other situations

where low dose is desired, such as in patients who have multiple scansfor

recurrent calculi. It should be remembered that the lowest exposure achievable

should always be pursued, and these studies should only be used in situations

where they will af-fect clinical decision making.

Bladder stones may occur

secondary to transport from the ureter or arise de novo. Most cases of bladder

stones are secondary to urinary stasis such as occurs with bladder outlet

obstruction from neurogenic bladders or prostatic enlarge-ment. The diagnosis

of bladder stones is similar to those in the upper urinary tract. Finally,

urethral stones occur, and in males the vast majority are present as a result

of passage from the bladder or above. In women, urethral stones are most

fre-quently the result of urethral diverticula, which result in uri-nary stasis

and stone formation.

Related Topics