Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Other Finfishes

Tunas

Tunas

Tunas are identified with Japanese cuisine and are usually served raw

(as sashimi) or as broiled fillets (Teriyaki). Yellowtail tuna (Seriola quin-queiradiata) is one of the

most popular speciescultured in Japan. The body size determines the name used

commercially. Yellowtail tuna culture refers to the rearing of juvenile up to

hamachi size (2–3 kg); commercial preference is for buri size (5–7 kg).

Juveniles used for net-cage culture are from natural supplies. They are

collected in May and June in the seas of southern Japan by fishermen specially

licensed to catch them with hand nets or round haul nets. Fish farmers release

them directly into the net-cages for on-growing. The yellowtail (tuna) culture

cycle is around two years. Within a year, the fish can weigh more than 1 kg

each and within a period of two years they may attain about 5–7 kg, which is a

profitable market size. The optimum temperature for growth is between 24 and

26°C. A sudden drop in temperature due to heavy rains may adversely affect the

health condition of the fish.

Eggs are collected from mature wild or cultured broodstock by stripping.

It takes cultured brood stock three years to reach a well-matured brood stock

weighing more than 5 kg, which produces 0.5 million eggs, and 6–8 kg, which may

produce 1 million eggs. The spawning season starts in February and continues

until June, depending on the ambient water temperature. Spawning can be induced

by the injection of HCG (600 IV/kg) of fish into the dorsal muscles, which can

achieve final maturation in two to three days. After fertilization viable

floating eggs are separated and transferred into incubation or larval tanks.

Hatching occurs after 70 hours under optimum temperatures of 18–21°C. Initial

larval feeding starts with rotifers at three to four days. When the larvae

reach 8–8.5 mm, Artemia nauplii and

marine copepods are fed in addition to rotifers. Larvae larger than 12 mm are

fed on adult Artemia or sometimes

fish eggs or formulated microdiets. The larvae grow up to about 23 mm in length

during May and survival rates are about 10 per cent when stocked in 100 m3 tanks at a water temperature of

22°C. Rotifers and Artemia are usually

enriched with emulsified lipids rich in n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids

(HUFA). When Artemia without

enrichment is fed, abnormalmortalities occur from the sixth day.

Recent studies have clearly shown that brood stocks of yellowtail tuna

can be fed with extruded pellets (soft dry pellets in place of raw

fish or moist pellets). Various studies on the nutritional requirements

using single moist pellets have been successful but the results do not appear

suitable for application in dry pellets. Regardless of the type of diet, the

digestibility of proteins in various feedstuffs is not different from other

fish species. It is generally high, being more than 85 per cent for soybean,

corn gluten, and feather and fish meals. Study of protein and energy requirements

for maximum growth of yellowtail are generally higher than those of other

fishes, probably due to their faster growth and higher swimming activity. Most

of the lipids (highly unsaturated fatty acids) commonly used in fish feeds are

highly digestible (90 to 99 per cent) in yellowtail tuna. Growth rate and feed

efficiency

are dependent on the dietary HUFA content, reaching maximum at a level

of 1.6 to 2.1 per cent. Yellowtail tuna does not seem to require supplemental

phosphorus in the fish-meal-based diet.

Farming of northern bluefin tuna (Thunnusthynnus)

is restricted now to a few Mediterrannean countries (Agius, 2002). The quota

allowed by the ICCAT (International Commission for Conservation of Atlantic

Tunas) restricts the individual transferable quotas based on a formula

calculated on previous catch and investment history. Mediterranean countries

are limited to a total 30 000 tons of allowable catch. Spain and Malta farmed

8000–9000 tons in the year 2001 and around 11 000–13 000 tons in 2002. Greece

and Libya are now starting bluefin tuna farming.

Tuna farming in cages is restricted to a short season in May to July.

They are caught in purse seine nets in stress-less condition. Farmed tuna has

better meat quality and meets the requirements for sashimi markets. Farming is

done in fattening cages made of strong, flexible polyethylene material. It is

important that towing cages have a solid structure, as stocking sites may be

located 200–300 miles away and the towing speed has to be slow to avoid too much

stress on the young fish. Towing speed is reduced to 1 knot per hour for

transport cages (90 m in circumference). Transport costs can be as high as US$

2500 per tugboat per day. Insurance cover is ensured for towing and culture in

cages. Mortality during farming once settled in cages or pens is usually not

more than 1 per cent.

Tunas are fed with trash fish, horse mackerels or Atlantic mackerels,

depending on the size of the tunas in the cages. When fed with sardines and

squids large quantities may be needed, e.g. a 500-ton farm may require 20–25

tons of sardines per day. Tunas consume frozen feeds such as sardines, which

sink to the bottom of cages.

Fish are ready for harvest by October. Some farmers complete the harvest

by December, while others continue until February or March. Air transport to

the market is preferred when available, as tunas for sashimi will be more

attractive in the fresh state. If it is not possible to use aerial transport,

the harvest may have to be sold frozen, but fresh fish have a better price in

the market. Fish to be sold fresh are caught by stunning, using an electrical

gadget. Fish

which have to be frozen before shipping are caught by the lowering a

small net into the cage. The harvested fish are crowded into a square net with

a V-shape projection on one side and an open window to allow the fish to swim

into it. The fish are removed by pulling up the net/cage on a floating

platform. Freezing of the harvest is often restricted by the blast freezing

capacity of the processing ship, which is usually 20 tons per day and continues

for 10 days. From the processing ship the frozen fish are moved to a reefer

ship, which takes the cargo to the market, which is mainly in the Far East. The

large tuna harvested are placed on a soft surface on board the ship. The price

of fresh tuna depends on the market in Japan and on airfreight charges. Fresh

fish are treated more carefully, and are cooled down quickly and individually

placed in boxes for freighting.

Japanese researchers achieved the first full-scale breeding of

endangered bluefun tuna in late June 2002, in Fisheries Laboratory of Kinki

(FFI, 2002). The matured tuna spawned around one million eggs, and the

scientists expect around 800 000 to hatch. Breeding success means a breakthrough

for a stable, inexpensive supply of bluefin tuna. Adults can measure up to

three metres and weigh about 550 kg.

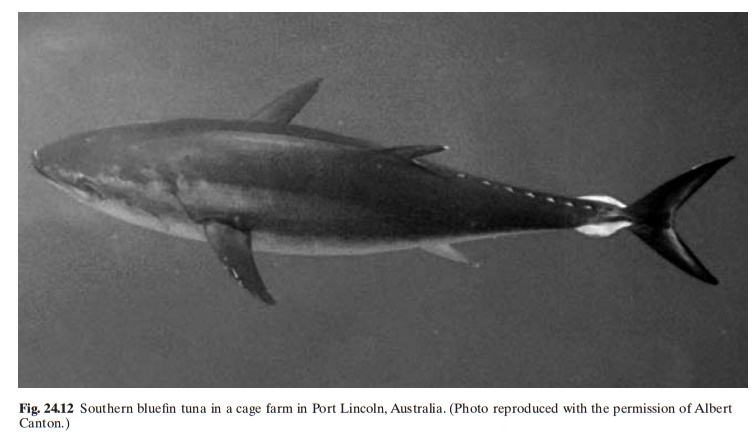

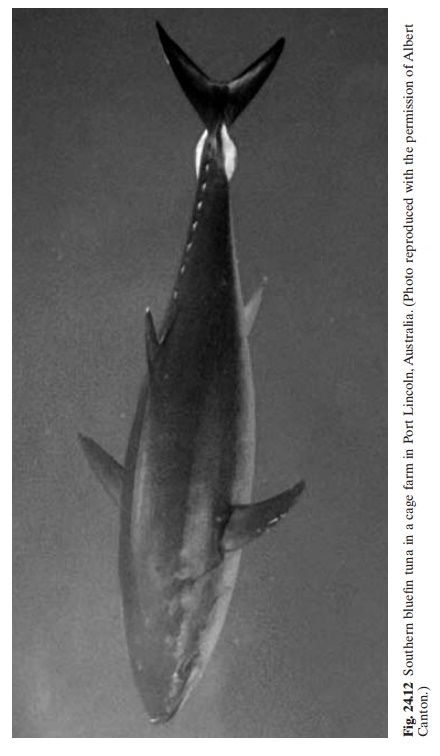

Southern bluefin (Thunnus maccoyi)

(fig. 24.12) have attracted prices of upto US$ 50/kg in Japan. Attempts to

breed bluefin are taking place in Australia and the Mediterranean countries

where captured bluefin are being raised in captivity. Environmentalists have

been calling for restrictions on the fisheries of Australian southern bluefin

tuna, which accounts for limiting the bluefin catch to a permitted quota of

5265 tons, utilised for stocking tuna cage farms. The benefits of farming are

not only to the owners; the spin-off industries such as transport and freight

are also beneficiaries.

By now most people know of the success of tuna farming in the regional

South Australian Town of Port Lincoln, where a complete industry, almost on the

verge of destruction, was completely turned around by the techniques of

Twelve months later commercial tuna farming began in Port Lincoln, although it was

limited by the old catching and towing system. In 1993 fish caught by purse

seine nets were towed at extremely slow speeds of 1 knot per hour, taking about

14 hours for the vessels to return to unload their catch in Port Lincoln. A

year later huge storms effectively wiped out 70 per cent of fish held in the

farms. Since then there have been continued improvements in grow-out systems

and lower fish mortalities, which have resulted in a production of over 8000

tons. There are at present about 15 southern bluefin farms on 18 sites, of

approximately 20 to 30 hectares in area. There are about 130 pontoons of 40

metres in depth, governed by the toughest environmental monitoring funded by

the industry on a quarterly basis from 2001 through the South Australian Government.

This quarterly regional monitoring has been expanded to include a more

intensive water quality and bottom fauna survey of both farm and non-farm

sites. Regulations governing the farming include (a) a maximum stocking rate of

4 kg per cubic metre of water, (b) a maximum of 400 tons of fish in a 30 ha

site, (c) minimum of 1 km distance between sites, and (d) a minimum clearance

of 5 metres between the fish net and the seabed.

The technology of farming involves finding the fish and getting it on board

while causing a minimal amount of stress in order to ensure premium quality to

the overseas sashimi market. Understanding of the transfer of southern bluefin

tuna, the towing of fish, the movement of pontoons and subsequent transfer on

to farms have improved gradually over the years. The industry is now able to

understand better the impact of stress on grow-out mortalities and growth rates

and the effect of water quality deterioration. The industry was able to use the

old-style boats and factories, so that the financial strain during the early

days was reduced. Over the years, the industry has developed dedicated

equipment such as onshore freezing plants. These have now been joined by the

new nitrogen freezing systems, which most farmers have built on to their

vessels for processing at sea. Many companies now have new multipurpose vessels

which can both tow and service the pontoons. High-strength cages are now being

manufactured locally – a 126 m circumference, 450 mm double collar seacage

wasbuilt incorporating new tuna stanchions up to 1.6 m high. The strong, sturdy

and stable stanchions are required to protect the employees against the threat

of sharks which are keen to take advantages of the tempting supply of tuna on

the other side of the cages. The latest advance has been to develop a stanchion

that acts as a float (FFI, 2002).

Japan has been trying to grow out northern bluefin larvae now since the

1980s. Progress has been minimal due to problems caused by collision and

cannibalism within the tanks. In addition, southern bluefin tunas do not spawn

in the wild until 10–11 years of age, while northern bluefin spawn at four to

five years of age. There is an indication that solutions to the problems of

fish collision and cannibalism within the tanks will demand heavy research

investment in both time and money. Given the delicate nature of tuna

propagation, it will take some time before propagation could make any

significant contribution to southern bluefin tuna production. This does not

prevent concentrated effort on globally distributed species like the tunas if

scientists decide on a species such as yellowtail tuna for which some of the

essential data are available.

The Inter-American Tropical Commission’s Achotines Laboratory, established to investigate the culture and captive spawning of tunas and billfishes, worked between 1993 and 2001 with several Japanese scientists on the spawning and rearing to sexual maturity of tuna species. Black skipjack captured in the wild spawned for extended periods. Eggs and larvae hatched in captivity were used in various experiments through 1994; early juvenile black skip-jack (Euthynnus lineatus) collected at sea were reared at the lab. By 1996 research emphasis was shifted to yellowfin tuna that were familiar to the scientists. Brood stock yellowfin tuna are fed squids, herring and anchovy supplemented with vitamins and minerals at about 2 to 4.5% of their body weight per day. Two to three year old yellowfin brood stocks in tanks have been spawning almost daily since October 1996 (FFI, 2002).

Spawning can be intermittent during February and March, and generally occurs from early afternoon to late

evening. The number of fertilized eggs collected after spawning ranges from

several hundred to several million. Fertilized eggs are hatched in 300

cylindrical incubation tanks. Juveniles are reared for five to six weeks and

have survived up to about 100 days.

Related Topics