Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Other Finfishes

cod (Gadus morhua)

Cod

Dried salted cod (bacalao) is a delicacy. Capture fisheries of cod (Gadus morhua) are now much reduced. Cod

was the base of the lucrative North Atlantic fishery, exploited by Britain,

France and Portugal since the 16th century. Cod grows to a large size, reaching

a maximum of over 100 kg and 2 metres, and is highly fecund, each female laying

about four to seven million eggs, but the spawning stock of cod has reduced

from 277 000 tons in 1971 to 67 000 tons in 1999 (Anonymous, 2003).

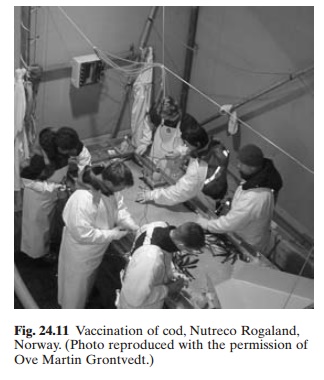

Owing to its high food value and price, and also the need for enhancing

production through artificial stocking, aquaculture of cod is highly

encouraged. The first cod culture trials were done in Norway in 1884 and

yolk-sac cod larvae were stocked in Norwegian bays in 1886, though the full

life cycle of cod was only closed in 1977 (Morais et al., 2001). Cod spawn naturally in captivity and the larvae have

good survival, showing fast growth rate in low temperatures.

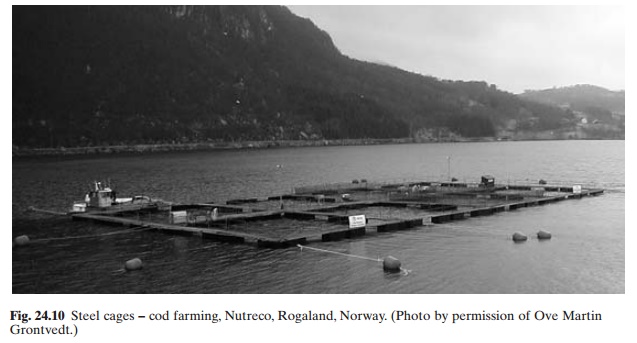

According to FAO estimates, the world production of farmed cod was 167

tons in 2000; the lead producing country was Norway. Commercial farming of cod

is being initiated in Britain and the USA. Intensive culture of cod has been

practised in both flow-through and recirculating sea water systems without

recourse to green water. However, better performance has been achieved using

recirculating systems, but with good water quality, avoiding fluctuations in

temperature, oxygen and ammonia. This is usually achieved by water flow rates

as high as 1% per minute, when high survival in high-stocking densities can be

achieved. Larval cod can be weaned into commercial diet 21 days after hatching,

but without feed supplementation by Artemia

larval growth is affected (Kling, 1998).

Cod needs high protein content in the diet, which increases the

production costs. The addition of more lipids in the diet saves on protein,

through the protein-saving action of the added lipids but causes fatty liver, which reduces the

value of cultured fish (Jobling, 1986, 1991; Jobling et al., 1993).

To minimise protein content, and inducing the protein-sparing action

through addition of lipids, formulated diets having various ranges of protein

(48–58%) and lipids (12–16%) in different combinations were fed to juvenile cod

(233 g) (Morais et al., 2001). High

content of lipids in the diet spared protein as indicated above. More efficient

use of proteins could be noticed at the end of 12 weeks’ growth – the diet with

48% protein and 16% fat seemed to be the best compromise between growth, feed

utilization and costs. Higher lipid content in the diet induced a higher

Hepato-Somatic Index (HSI), resulting in fatty liver, but in these tests one of

the objectives was to find out if the higher fat content in the diets not only

caused a sparing action on proteins, thereby saving costs of feed, but also if

the deposition of more fat, induced in the liver, could be made use of in the

production of more cod liver oil, a well known health supplement. The tests

conclusively proved that both these resulted as a consequence of feeding a

relatively economical, low-protein (48%) and high-fat (16%) diet to juvenile

cod. Even though the lipid profiles of the liver oils of the test fish and

natural ‘cod liver oil’ were found to be same, the former were found to have

more high saturated fats.

Commercial farming is practised in both flow-through and recirculation

seawater sys- q tems, but good water quality, without fluctuations in

temperature, is required. Cod farming, after salmon farming, is considered to

be the second wave in aquaculture in Norway. The demand for cod is greater than

the supply and Norwegian farmed cod production can reach 175 000 tons by 2010

and is predicted to increase to 400 000 tons by 2015. The biggest hatchery

built so far has functioned well in Norway and has given confidence in

achieving significant improvement, in view of the strong demand for this

popular white fish. There is the clamour for licenses by investors. Total cod

fry production in Norway is estimated at four million, which could yield 3000

tons of marketable fish in 2005. Breakthrough has been achieved in replacing

live rotifers with dry feed. Larval cod can be weaned with a commercial diet 21

days after hatching. The industry can deliver different sizes of fry up to 100

grams, depending on how the on-growing is organized. Market-ready fish is expected

in two years. Major enterprises in cod farming, which require big investment,

may be a major challenge when salmon companies in Norway are struggling to make

a profit. The demand for cod is likely to persist, but the cost of production

must be reduced by at least 25% to enable producers to operate profitably.

Although high-energy diets in the grow-out period give a lower feed con

Related Topics