Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Other Finfishes

Turbot (Scophthalmusmaximus - family Scophthalmidae)

Turbot

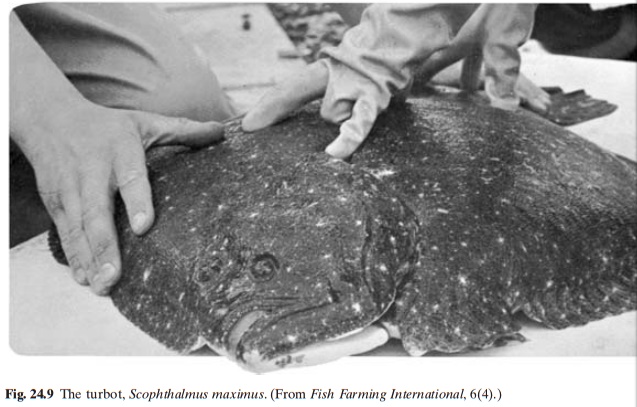

Among the flatfishes, the turbot Scophthalmusmaximus (family Scophthalmidae) (fig. 24.9)has so far proved to be the one with the greatest immediate aquaculture potential. As a result of several years of research, especially in the United Kingdom and France, the main elements of a culture technology have emerged and pilot-scale production in these countries, and in Spain, has been initiated in recent years.

Turbot is a highly priced marine fish for which there is a good demand, especially in Northern European markets. Natural production is reported to be insufficient to meet the demand. The species is known to be hardy and, though carnivorous in nature, can be fed on various feedstuffs and prepared feeds. Growth rates are fast and, at a water temperature of about 18°C, 5 cm juveniles reach a marketable size of 300–400 g in one year, and over 1000 g in about 18 months. The maximum recorded length of the species is 100 cm, but fish of about 50 cm are more common in the markets.

Though early attempts at turbot culture were handicapped by inadequate supplies of seed stock, it is now possible to mass-produce fry in hatcheries. As culture has to be based on complete artificial feeding, intensive systems of culture are adopted mainly in tanks and cages. Cooling water from power stations has been used to maintain optimum temperatures and obtain accelerated growth rates.

Controlled spawning and hatchery production of juveniles

Two- to three-year-old female turbot (of 2 kg weight) have been observed to reach sexual maturity and spawn in the wild from May to August. Males reach maturity in the second year (1 kg body weight). The annual fecundity is about a million eggs per kg body weight. The diameter of the eggs varies from 0.9 to 1.2 mm. Mature fish will spawn naturally in tanks. Circular indoor tanks up to 2.7 m3 in size, supplied with warm water and continuous high-intensity illumination (up to 3000 lux), have been successfully used for spawning and larval rearing. The size and colour of the tanks do not seem to have any significant effect. Eggs and milt have also been obtained by manual stripping and artificial fertilization has been achieved. Through proper management of brood stock, it is now possible to produce eggs all year round. Temperature is maintained between 10 and 15°C, and the photoperiod is adjusted to obtain spawning at any time of the year. The eggs are incubated at about 12°C in filtered sea water treated with antibiotics. Newly hatched larvae are reared at densities of 30–45 larvae per , in 60–450 tanks. Temperatures between 18 and 20°C are maintained with 90 per cent water exchange every day.

The comparatively small size of turbot hatchlings (3.11 mm length and 0.10–0.15 mg weight) makes it necessary to handle them with special care and to feed the right sized live foods to obtain reasonable survival rates. The rotifer Brachionus plicatilis and nauplii and metanauplii of the brine shrimp Artemia salina are the most commonly used larval foods. It has been suggested that the algae used to feed the rotifer affect the growth and survival of the larvae

(Howell, 1979). When fed on Isochrysis galbana rather than Dunaliella tertiolecta, the larvae grew better and mortality was lowered. From the first day of hatching to about the eighth day, Brachionus is the preferred food; Artemia nauplii are then added and the rotifer reduced, usually terminating by about the eleventh day. Naupliar feeding is continued until the larvae develop into metamorphosed juveniles at a size of 25–30 mm in about 30–40 days. From about the eighteenth day, larger metanauplii of Artemia are used.

The juveniles, weighing 55–105 mg, are weaned to artificial diets in less than two weeks. Dry pellet crumbs (400 mm size) give satisfactory results, but greater success has been achieved by the use of moist pellets, when survival rates have been increased to about 50 per cent. Experimental work (Person-Le Ruyet etal., 1983) seems to show that expanded pelletsenriched with inosine (a chemical attractant) increase food intake during the beginning of the weaning period, but the economics have yet to be determined. After weaning, dry pellets are normally used for feeding, and in about three months after hatching the fry attain a weight of around 2 g.

In areas where the temperature is much below the optimum range of 18–20°C, the fry are initially reared indoors, in heated water, and then transferred outside. If they are to be transferred during the summer months, they are grown indoors up to a weight of 5 g, but if they are to be transferred during winter, they are grown to at least 20 g size. Survival below 5–6°C is very low. In well-oxygenated water they can tolerate temperatures between 25 and 30°C, and salinities ranging from brackish to 40 ppt. For rearing up to 20 g size, dry pellet feed is commonly used, but for growth beyond that moist pellets (containing 25 per cent trash fish, as well as fish and meat meal, wheat middlings, brewer’s yeast, cod liver oil and a vitamin premix) are recommended. Moist pellets made from a mixture of industrial fish and dry compound meal have been used to feed 5 g fish at the rate of 2.6 per cent of body weight at 10°C and at 4.5 per cent at 15°C (Jones, 1981). Juveniles of 50 g weight are fed at 1.1 per cent of body weight at 10°C and at 2 per cent of body weight at 15°C. Dry pellets are not easily accepted by larger fish, but trash fish forms an excellent feed. After a period of one year’s growth under favourable conditions, turbot attain weights of 175–350 g in indoor tanks in areas with higher water temperatures, while a weight of about 120 g only may be reached in outdoor tanks.

Grow-out

As commercial grow-out is still in the early stages, there is only limited information available. However, early trials have shown that turbot young can be grown to market size with high levels of survival. Marketable-size fish can be raised in 12–14 months with proper feeding and environmental control, especially of temperature. The optimal temperature appears to

be 15 to 19°C. Though heated water may have to be used in growing tanks, the quantity of water required is not large as turbot are reported to require tanks with a surface area only equivalent to their own.

In tanks fed with cooling water from a nuclear power plant in North Wales, UK, a stocking density of 25–55 kg/m3 of 10–1500 g fish has been maintained, but this required continuous re-oxygenation using special equipment (Jones, 1981). Several foodstuffs and compound diets have been used for on-growing.

Chopped or whole trash fish and industrial fish are well accepted by turbot, but it is believed that when such feed is used for a long period the survival rates are adversely affected. So moist compound pellets are recommended. However, fish like mackerel, sprat or mysids stimulate the appetite of turbot and so incorporation of these fish in a ground form to the extent of 20–25 per cent dry weight (as suggested for juvenile growing) has been recommended to improve feeding and growth rates, especially at lower temperatures.

Experimental grow-out of young turbot collected from the wild and raised in hatcheries in floating sea cages of 2.9 m3 size in Scotland (Hull and Edwards, 1979) has shown that they can be grown successfully in cages, with very high survival rates. To obtain high growth rates, the juveniles had to be reared in land-based nurseries over the first winter period, to a size above 50 g, and then transferred to the cages. The maximum density tried was 41 kg/m3 or 240 fish/m3 and this did not depress growth. Moist pellet preparations with a protein content of about 36–39 per cent were used as feed. In the ambient temperature ranging from 6 to 16°C, a market size of 450–500 g was reached in 18 months of on-growing and after another 12 months a weight of 1.2 kg could be attained.

Vibriosis is the most common bacterial disease recorded for young turbot and this can cause high levels of mortality. The antibiotic oxytetracyclin, administered through feed at a concentration of 75 mg/kg body weight per day and also as a bath at 53 mg/ has been found to be effective. In addition, infestation by Trichodina spp. has been observed. This is controlled by one-hour baths of formalin at a concentration of 1 : 6000. In rearing facilities using power-station cooling water, gas bubble disease can occur, but is controlled by changing to ambient sea water.

Related Topics