Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Applied physiology and pharmacology : Anesthesia and the lung

The hypoxemic patient

The hypoxemic patient

When a patient becomes hypoxemic, we first apply supplemental oxygen. Won-derfully, the patient’s saturation usually responds. Should it fall again, we can simply increase the inspired oxygen concentration once again – but we are not solving the problem. The adequate saturation may lull us into an inappropriate sense of security regarding the well-being of the patient.

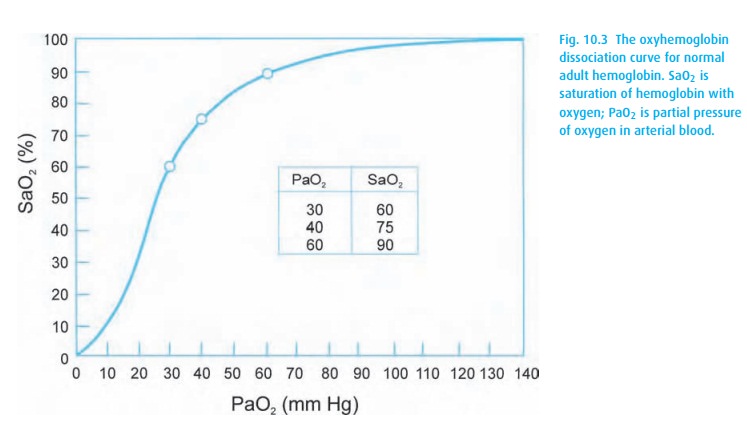

Assume this patient requires 50% inspired oxygen to maintain a SpO2 of 90%, much less than we would expect with that FiO2. We estimate the degree of the oxygenation problem by looking at the difference between the alveolar and arterial oxygen concentrations. With a SpO2 of 90%, we can assume the PaO2 to be around 60 mmHg (from Fig. 10.3).

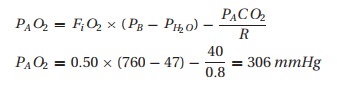

Next, we need to know what the alveolar concentration of oxygen would be in the patient breathing 50% oxygen. The alveolar air equation comes to our aid. We estimate PACO2 and R to be 40 mmHg and 0.8, respectively.

Therefore, we would expect the PaO2 to be close to 300 mmHg instead of the observed 60 mmHg. This “A-a difference” (often mislabeled an A – a gradient) may be due to a problem with oxygen diffusion and/or matching of ventilation and perfusion (V/Q). In healthy patients some 4% of the venous blood will manage to make it through a right (venous blood in the pulmonary artery) to left (arterial blood in the pulmonary vein) shunt. Thus, normally we expect to see a slightly lower partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood than in alveolar gas. However, a patient requiring 50% inspired oxygen to barely maintain a SpO2 of 90% should worry us greatly.

If a patient is hypoxemic on room air, giving supplemental oxygen is a great first step, but the source of the hypoxemia should be sought and appropriately treated.

Conscious sedation

The patient receiving intravenous sedation presents another situation in which the alveolar air equation can help. Some physicians routinely place these patients on supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, resulting in a PaO2 of 150 mmHg or more (well into the flat part of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve: Fig. 10.3). If the patient now hypoventilates, his PaCO2 will rise and PaO2 will fall, but his SpO2 can stay deceptively normal. Thus, not giving supplemental oxygen (to a patient with normal oxygenation) will make the SpO2 a sensitive indicator of respiratory depression. Once a drop in saturation occurs, we need to treat the patient’s hypoventilation.

Related Topics