Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Applied physiology and pharmacology : Anesthesia and the lung

Mechanical ventilation

Mechanical ventilation

Many

patients require mechanical ventilation in the operating room or inten-sive

care unit. While an intubated patient can breathe spontaneously through an

endotracheal tube (which imposes significant resistance), many operative

proce-dures require muscle relaxation, making mechanical ventilation mandatory.

Most anesthesia machines are equipped with ventilators capable of providing

volume-or pressure-controlled ventilation. For volume-controlled ventilation,

the oper-ator sets a tidal volume, respiratory rate, and inspiratory to

expiratory time ratio (I : E ratio), and the ventilator does its

best to comply. If compliance deteriorates, the machine will generate

additional pressure (up to a set limit) in an attempt to deliver the desired

tidal volume. In pressure-controlled mode, as the name sug-gests, the selected

pressure will be maintained for a set time, which might mean variable tidal volumes,

depending on the patient’s pulmonary compliance and resistance.

In

general, ventilators used in the ICU offer more options than anesthesia machine

ventilators. For example, they might offer SIMV (synchronized inter-mittent

mandatory ventilation) in which the mechanical breath is synchronized with the

patient’s inspiratory effort, and the patient can breathe spontaneously between

mechanical breaths. SIMV is often combined with pressure support ven-tilation

(PSV), in which spontaneous respiratory efforts are met with a set level of

positive pressure, assisting with inhalation and designed to overcome the

resis-tance imposed by the endotracheal tube and ventilator.

Another

ventilator mode that requires explanation is continuous positive air-way

pressure (CPAP) and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Ordinarily, when

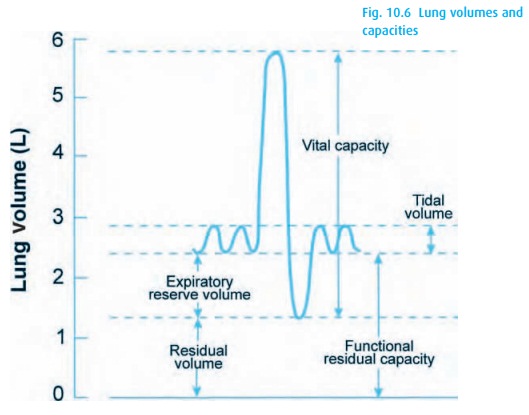

we exhale, some gas remains in the lungs (the FRC – see Fig. 10.6). Supine positioning and anesthesia reduce

the FRC, potentially resulting in hypoxemia. Normal FRC can be restored with the

addition of end-expiratory pressure, PEEP. It becomes particularly useful if

increased intra-abdominal pressure or extravas-cular fluid (pulmonary edema,

atelectasis, aspiration of gastric contents or res-piratory distress syndrome

(ARDS)) decreased FRC or caused collapse of alveoli. Two major factors limit

the amount of PEEP that we can apply: (i) the increase in intrathoracic

pressure will impede venous return; and (ii) the inspired tidal vol-ume is

administered on top of this baseline positive pressure, causing increased peak

inflation pressure and possibly barotrauma.

Related Topics