Chapter: Security in Computing : Elementary Cryptography

The Uses of Encryption

The Uses of Encryption

Encryption algorithms alone

are not the answer to everyone's encryption needs. Although encryption

implements protected communications channels, it can also be used for other

duties. In fact, combining symmetric and asymmetric encryption often

capitalizes on the best features of each.

Public key algorithms are

useful only for specialized tasks because they are very slow. A public key

encryption can take 10,000 times as long to perform as a symmetric encryption

because the underlying modular exponentiation depends on multiplication and

division, which are inherently slower than the bit operations (addition,

exclusive OR, substitution, and shifting) on which symmetric algorithms are

based. For this reason, symmetric encryption is the cryptographers'

"workhorse," and public key encryption is reserved for specialized,

infrequent uses, where slow operation is not a continuing problem.

Let us look more closely at

four applications of encryption: cryptographic hash functions, key exchange,

digital signatures, and certificates.

Cryptographic Hash Functions

Encryption is most commonly

used for secrecy; we usually encrypt something so that its contentsor even its

existenceare unknown to all but a privileged audience. In some cases, however,

integrity is a more important concern than secrecy. For example, in a document

retrieval system containing legal records, it may be important to know that the

copy retrieved is exactly what was stored. Likewise, in a secure communications

system, the need for the correct transmission of messages may override secrecy

concerns. Let us look at how encryption provides integrity.

In most files, the elements

or components of the file are not bound together in any way. That is, each byte

or bit or character is independent of every other one in the file. This lack of

binding means that changing one value affects the integrity of the file, but

that one change can easily go undetected.

What we would like to do is somehow put a seal

or shield around the file so that we can detect when the seal has been broken

and thus know that something has been changed. This notion is similar to the

use of wax seals on letters in medieval days; if the wax was broken, the

recipient would know that someone had broken the seal and read the message

inside. In the same way, cryptography can be used to seal a file, encasing it

so that any change becomes apparent. One technique for providing the seal is to

compute a cryptographic function, sometimes called a hash or checksum or message digest of the file.

A one-way function can be

useful in an encryption algorithm. The function must depend on all bits of the

file being sealed, so any change to even a single bit will alter the checksum

result. The checksum value is stored with the file. Then, each time the file is

accessed or used, the checksum is recomputed. If the computed checksum matches

the stored value, it is likely that the file has not been changed.

A cryptographic function,

such as the DES or AES, is especially appropriate for sealing values, since an

outsider will not know the key and thus will not be able to modify the stored

value to match with data being modified. For low-threat applications,

algorithms even simpler than DES or AES can be used. In block encryption

schemes, chaining means linking each

block to the previous block's value (and therefore to all previous blocks), for

example, by using an exclusive OR to combine the encrypted previous block with

the encryption of the current one. A file's cryptographic checksum could be the

last block of the chained encryption of a file since that block will depend on

all other blocks.

As we see later in this

chapter, these techniques address the nonalterability and nonreusability

required in a digital signature. A change or reuse will be flagged by the

checksum, so the recipient can tell that something is amiss.

The most widely used cryptographic hash

functions are MD4, MD5 (where MD

stands for Message Digest), and SHA/SHS

(Secure Hash Algorithm or Standard). The MD4/5 algorithms were invented by Ron

Rivest and RSA Laboratories. MD5 is an improved version of MD4. Both condense a

message of any size to a 128-bit digest. SHA/SHS is similar to both MD4 and

MD5; it produces a 160-bit digest.

Wang et al. [WAN05] have announced cryptanalysis attacks on

SHA, MD4, and MD5. For SHA, the attack is able to find two plaintexts

that produce the same hash

digest in approximately 263 steps, far short of the 2 80 steps that would be expected of a 160-bit hash

function, and very feasible for a moderately well-financed attacker. Although

this attack does not mean SHA is useless (the attacker must collect and analyze

a large number of ciphertext samples), it does suggest use of long digests and

long keys. NIST [NIS05, NIS06] has studied the attack carefully and

recommended countermeasures.

Key Exchange

Suppose you need to send a

protected message to someone you do not know and who does not know you. This

situation is more common than you may think. For instance, you may want to send

your income tax return to the government. You want the information to be

protected, but you do not necessarily know the person who is receiving the

information. Similarly, you may want to use your web browser to connect with a

shopping web site, exchange private (encrypted) e-mail, or arrange for two

hosts to establish a protected channel. Each of these situations depends on

being able to exchange an encryption key in such a way that nobody else can

intercept it. The problem of two previously unknown parties exchanging

cryptographic keys is both hard and important. Indeed, the problem is almost

circular: To establish an encrypted session, you need an encrypted means to

exchange keys.

Public key cryptography can help. Since

asymmetric keys come in pairs, one half of the pair can be exposed without

compromising the other half. To see how, suppose S and R (our well-known sender

and receiver) want to derive a shared symmetric key. Suppose also that S and R

both have public keys for a common encryption algorithm; call these kPRIV

-S, kPUB-S, kPRIV -R, and kPUB -R, for

the private and public keys for S and R, respectively. The simplest solution is

for S to choose any symmetric key K, and send E(kPRIV-S,K) to R.

Then, R takes S's public key, removes the encryption, and obtains K. Alas, any

eavesdropper who can get S's public key can also obtain K.

Instead, let S send E(kPUB-R, K) to

R. Then, only R can decrypt K. Unfortunately, R has no assurance that K came

from S.

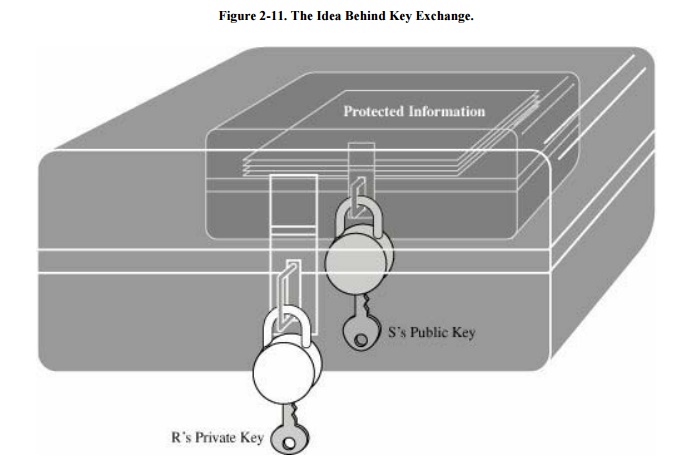

But there is a useful alternative. The solution

is for S to send to R:

E(kPUB-R, E(kPRIV-S, K))

We can think of this exchange in terms of lockboxes and keys. If S

wants to send something protected to R (such as a credit card number or a set

of medical records), then the exchange works something like this. S puts the

protected information in a lockbox that can be opened only with S's public key.

Then, that lockbox is put inside a second lockbox that can be opened only with

R's private key. R can then use his private key to open the outer box (something

only he can do) and use S's public key to open the inner box (proving that the

package came from S). In other words, the protocol wraps the protected

information in two packages: the first unwrapped only with S's public key, and

the second unwrapped only with R's private key. This approach is illustrated in

Figure 2-11.

Another approach not requiring pre-shared

public keys is the so-called DiffieHellman key exchange protocol. In this

protocol, S and R use some simple arithmetic to exchange a secret. They agree

on a field size n and a starting number g; they can communicate these numbers

in

the clear. Each thinks up a secret number, say,

s and r. S sends to R gs and R sends to S gr. Then S

computes (gr)s and R computes (gs)r,

which are the same, so grs = gsr

becomes their shared secret. (One technical detail has been omitted for

simplicity: these computations are done over a field of integers mod n; see Chapter 12 for more information on modular

arithmetic.)

Digital Signatures

Another typical situation

parallels a common human need: an order to transfer funds from one person to

another. In other words, we want to be able to send electronically the

equivalent of a computerized check. We understand how this transaction is

handled in the conventional, paper mode:

·

A check is a tangible object authorizing a financial transaction.

·

The signature on the check confirms authenticity because

(presumably) only the legitimate signer can produce that signature.

·

In the case of an alleged forgery, a third party can be called in

to judge authenticity.

·

Once a check is cashed, it is canceled so that it cannot be reused.

·

The paper check is not alterable. Or, most forms of alteration are

easily detected.

Transacting business by check

depends on tangible objects in a prescribed form. But tangible objects do not

exist for transactions on computers. Therefore, authorizing payments by

computer requires a different model. Let us consider the requirements of such a

situation, both from the standpoint of a bank and from the standpoint of a

user.

Suppose Sandy sends her bank

a message authorizing it to transfer $100 to Tim. Sandy's bank must be able to

verify and prove that the message really came from Sandy if she should later

disavow sending the message. The bank also wants to know that the message is

entirely Sandy's, that it has not been altered along the way. On her part,

Sandy wants to be certain that her bank cannot forge such messages. Both

parties want to be sure that the message is new, not a reuse of a previous

message, and that it has not been altered during transmission. Using electronic

signals instead of paper complicates this process.

But we have ways to make the

process work. A digital signature is

a protocol that produces the same effect as a real signature: It is a mark that

only the sender can make, but other people can easily recognize as belonging to

the sender. Just like a real signature, a digital signature is used to confirm

agreement to a message.

Properties

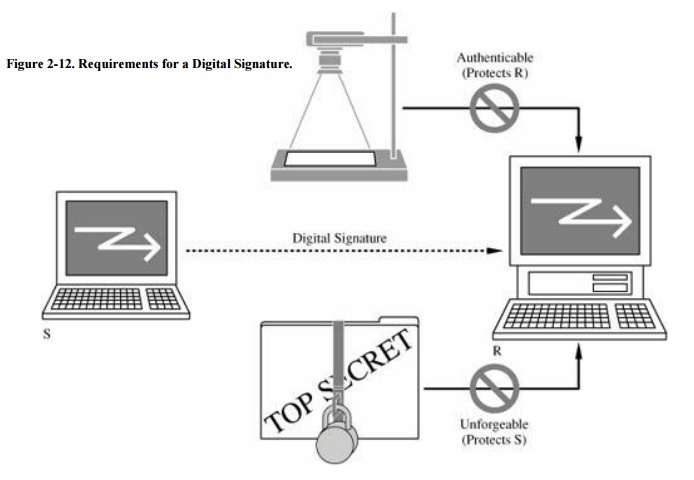

A digital signature must meet

two primary conditions:

·

It must be unforgeable. If person P signs message M with signature

S(P,M), it is impossible for anyone else to produce the pair [M, S(P,M)].

·

It must be authentic. If a person R receives the pair [M, S(P,M)]

purportedly from P, R can check that the signature is really from P. Only P

could have created this signature, and the signature is firmly attached to M.

These two requirements, shown

in Figure 2-12, are the major hurdles in

computer transactions. Two more properties, also drawn from parallels with the

paper-based environment, are desirable for transactions completed with the aid

of digital signatures:

·

It is not alterable. After being transmitted, M cannot be changed

by S, R, or an interceptor.

·

It is not reusable. A previous message presented again will be

instantly detected by R.

To see how digital signatures

work, we first present a mechanism that meets the first two requirements. We

then add to that solution to satisfy the other requirements.

Public Key Protocol

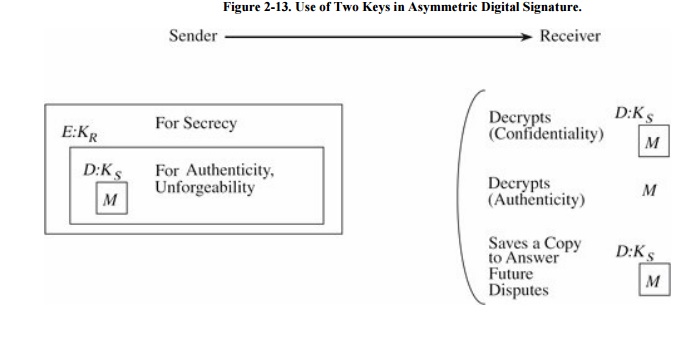

Public key encryption systems are ideally

suited to digital signatures. For simple notation, let us assume that the

public key encryption for user U is accessed through E(M, KU) and

that the private key transformation for U is written as D(M,KU). We

can think of E as the privacy transformation (since only U can decrypt it) and

D as the authenticity transformation (since only U can produce it). Remember,

however, that under some asymmetric algorithms such as RSA, D and E are

commutative, and either one can be applied to any message. Thus,

D(E(M, ), ) = M = E(D(M, ), )

If S wishes to send M to R, S uses the

authenticity transformation to produce D(M, KS). S then sends D(M, KS)

to R. R decodes the message with the public key transformation of S, computing

E(D(M,KS), KS) = M. Since only S can create a message

that makes sense under E(,KS), the message must genuinely have come

from S. This test satisfies the authenticity requirement.

R will save D(M,KS). If S should

later allege that the message is a forgery (not really from S), R can simply

show M and D(M,KS). Anyone can verify that since D(M,KS)

is transformed to M with the public key transformation of Sbut only S could

have produced D (M,KS)then D(M,KS) must be from S. This test

satisfies the unforgeable requirement.

There are other approaches to implementing

digital signature; some use symmetric encryption, others use asymmetric. The

approach shown here illustrates how the protocol can address the requirements

for unforgeability and authenticity. To add secrecy, S applies E(M, KR)

as shown in Figure 2-13.

Next, we learn about cryptographic certificates

so that we can see how they are used to address authenticity.

Certificates

As humans we establish trust

all the time in our daily interactions with people. We identify people we know

by recognizing their voices, faces, or handwriting. At other times, we use an

affiliation to convey trust. For instance, if a stranger telephones us and we

hear, "I represent the local government…" or "I am calling on

behalf of this charity…" or "I am calling from the

school/hospital/police about your

mother/father/son/daughter/brother/sister…," we may decide to trust the

caller even if we do not know him or her. Depending on the nature of the call,

we may decide to believe the caller's affiliation or to seek independent

verification. For example, we may obtain the affiliation's number from the

telephone directory and call the party back. Or we may seek additional

information from the caller, such as "What color jacket was she

wearing?" or "Who is the president of your organization?" If we

have a low degree of trust, we may even act to exclude an outsider, as in

"I will mail a check directly to your charity rather than give you my

credit card number."

For each of these

interactions, we have what we might call a "trust threshold," a

degree to which we are willing to believe an unidentified individual. This

threshold exists in commercial interactions, too. When Acorn Manufacturing

Company sends Big Steel Company an order for 10,000 sheets of steel, to be

shipped within a week and paid for within ten days, trust abounds. The order is

printed on an Acorn form, signed by someone identified as Helene Smudge,

Purchasing Agent. Big Steel may begin preparing the steel even before receiving

money from Acorn. Big Steel may check Acorn's credit rating to decide whether

to ship the order without payment first. If suspicious, Big Steel might

telephone Acorn and ask to speak to Ms. Smudge in the purchasing department.

But more likely Big Steel will actually ship the goods without knowing who Ms.

Smudge is, whether she is actually the purchasing agent, whether she is

authorized to commit to an order of that size, or even whether the signature is

actually hers. Sometimes a transaction like this occurs by fax, so that Big

Steel does not even have an original signature on file. In cases like this one,

which occur daily, trust is based on appearance of authenticity (such as a

printed, signed form), outside information (such as a credit report), and

urgency (Acorn's request that the steel be shipped quickly).

For electronic communication

to succeed, we must develop similar ways for two parties to establish trust

without having met. A common thread in our personal and business interactions

is the ability to have someone or something vouch for the existence and

integrity of one or both parties. The police, the Chamber of Commerce, or the

Better Business Bureau vouches for the authenticity of a caller. Acorn

indirectly vouches for the fact that Ms. Smudge is its purchasing agent by

transferring the call to her in the purchasing department. In a sense, the

telephone company vouches for the authenticity of a party by listing it in the

directory. This concept of "vouching for" by a third party can be a

basis for trust in commercial settings where two parties do not know each

other.

Trust Through a Common Respected Individual

A large company may have

several divisions, each division may have several departments, each department

may have several projects, and each project may have several task groups (with

variations in the names, the number of levels, and the degree of completeness

of the hierarchy). The top executive may not know by name or sight every employee

in the company, but a task group leader knows all members of the task group,

the project leader knows all task group leaders, and so on. This hierarchy can

become the basis for trust throughout the organization.

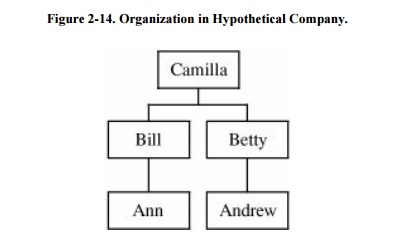

To see how, suppose two

people meet: Ann and Andrew. Andrew says he works for the same company as Ann.

Ann wants independent verification that he does. She finds out that Bill and

Betty are two task group leaders for the same project (led by Camilla); Ann

works for Bill and Andrew for Betty. (The organizational relationships are

shown in Figure 2-14.) These facts give

Ann and Andrew a basis for trusting each other's identity. The chain of

verification might be something like this:

·

Ann asks Bill who Andrew is.

·

Bill either asks Betty if he knows her directly or if not, asks

Camilla.

·

Camilla asks Betty.

·

Betty replies that Andrew works for her.

·

Camilla tells Bill.

·

Bill tells Ann.

If Andrew is in a different task

group, it may be necessary to go higher in the organizational tree before a

common point is found.

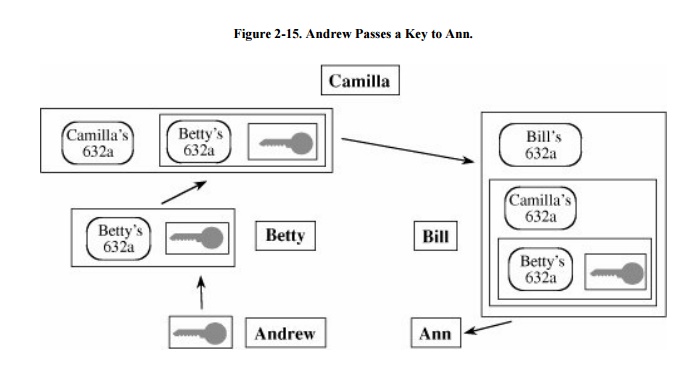

We can use a similar process for cryptographic

key exchange, as shown in Figure 2-15.

If Andrew and Ann want to communicate, Andrew can give his public key to Betty,

who passes it to Camilla or directly to Bill, who gives it to Ann. But this

sequence is not exactly the way it would work in real life. The key would

probably be accompanied by a note saying it is from Andrew, ranging from a bit

of yellow paper to a form 947 Statement of Identity. And if a form 947 is used,

then Betty would also have to attach a form 632a Transmittal of Identity,

Camilla would attach another 632a, and Bill would attach a final one, as shown

in Figure 2-15. This chain of 632a forms

would say, in essence, "I am Betty and I received this key and the

attached statement of identity personally from a person I know to be

Andrew," "I am Camilla and I received this key and the attached

statement of identity and the attached transmittal of identity personally from

a person I know to be Betty," and so forth. When Ann receives the key, she

can review the chain of evidence and conclude with reasonable assurance that

the key really did come from Andrew. This protocol is a way of obtaining authenticated

public keys, a binding of a key, and a reliable identity.

This model works well within a company because

there is always someone common to any two employees, even if the two employees

are in different divisions so that the common person is the president. The

process bogs down, however, if Ann, Bill, Camilla, Betty, and Andrew all have

to be available whenever Ann and Andrew want to communicate. If Betty is away

on a business trip or Bill is off sick, the protocol falters. It also does not

work well if the president cannot get any meaningful work done because every

day is occupied with handling forms 632a.

To address the first of these

problems, Andrew can ask for his complete chain of forms 632a from the

president down to him. Andrew can then give a copy of this full set to anyone

in the company who wants his key. Instead of working from the bottom up to a

common point, Andrew starts at the top and derives his full chain. He gets

these signatures any time his superiors are available, so they do not need to

be available when he wants to give away his authenticated public key.

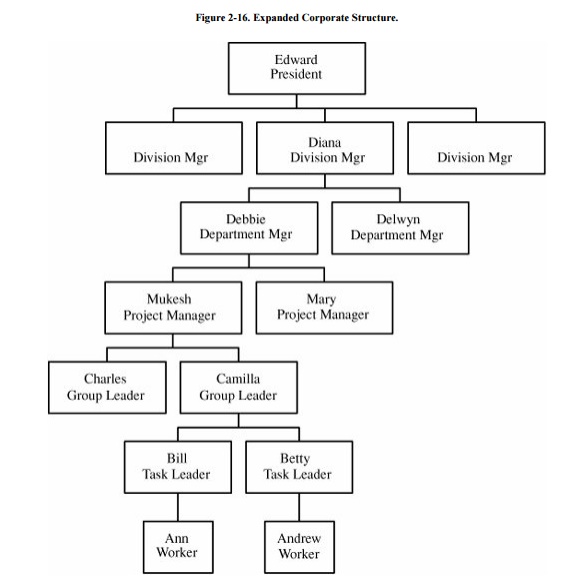

The second problem is resolved by reversing the

process. Instead of starting at the bottom (with task members) and working to

the top of the tree (the president), we start at the top. Andrew thus has a

preauthenticated public key for unlimited use in the future. Suppose the

expanded structure of our hypothetical company, showing the president and other

levels, is as illustrated in Figure 2-16.

The president creates a

letter for each division manager saying "I am Edward, the president, I

attest to the identity of division manager Diana, whom I know personally, and I

trust Diana to attest to the identities of her subordinates." Each division

manager does similarly, copying the president's letter with each letter the

manager creates, and so on. Andrew receives a packet of letters, from the

president down through his task group leader, each letter linked by name to the

next. If every employee in the company receives such a packet, any two

employees who want to exchange authenticated keys need only compare each

other's packets; both packets will have at least Edward in common, perhaps some

other high managers, and at some point will deviate. Andrew and Ann, for

example, could compare their chains, determine that they were the same through

Camilla, and trace the bottom parts. Andrew knows Alice's chain is authentic

through Camilla because it is identical to his chain, and Ann knows the same.

Each knows the rest of the chain is accurate because it follows an unbroken

line of names and signatures.

Certificates to Authenticate an Identity

This protocol is represented

more easily electronically than on paper. With paper, it is necessary to guard

against forgeries, to prevent part of one chain from being replaced and to

ensure that the public key at the bottom is bound to the chain. Electronically

the whole thing can be done with digital signatures and hash functions.

Kohnfelder seems to be the

originator of the concept of using an electronic certificate with a chain of

authenticators, which is expanded in Merkle's paper .

A public key and user's

identity are bound together in a certificate,

which is then signed by someone called a certificate

authority, certifying the accuracy of the binding. In our example, the

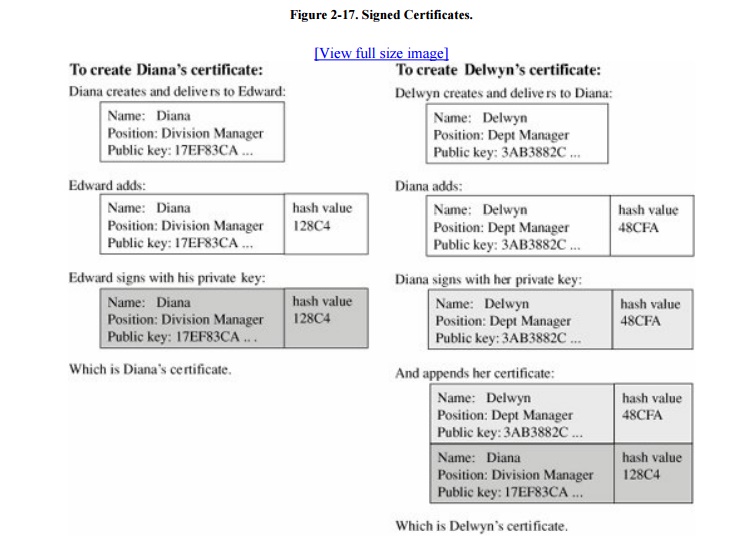

company might set up a certificate scheme in the following way. First, Edward

selects a public key pair, posts the public part where everyone in the company

can retrieve it, and retains the private part. Then, each division manager,

such as Diana, creates her public key pair, puts the public key in a message

together with her identity, and passes the message securely to Edward. Edward

signs it by creating a hash value of the message and then encrypting the

message and the hash with his private key. By signing the message, Edward

affirms that the public key (Diana's) and the identity (also Diana's) in the

message are for the same person. This message is called Diana's certificate.

All of Diana's department managers create

messages with their public keys, Diana signs and hashes each, and returns them.

She also appends to each a copy of the certificate she received from Edward. In

this way, anyone can verify a manager's certificate by starting with Edward's

well-known public key, decrypting Diana's certificate to retrieve her public

key (and identity), and using Diana's public key to decrypt the manager's

certificate. Figure 2-17 shows how

certificates are created for Diana and one of her managers, Delwyn. This

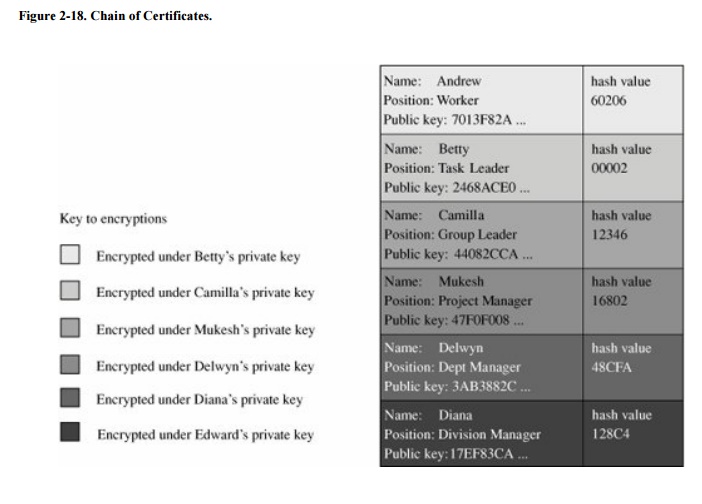

process continues down the hierarchy to Ann and Andrew. As shown in Figure 2-18, Andrew's certificate is really his

individual certificate combined with all certificates for those above him in

the line to the president.

Trust Without a Single Hierarchy

In our examples, certificates were issued on

the basis of the managerial structure. But it is not necessary to have such a

structure or to follow it to use certificate signing for authentication. Anyone

who is considered acceptable as an authority can sign a certificate. For

example, if you want to determine whether a person received a degree from a

university, you would not contact the president or chancellor but would instead

go to the office of records or the registrar. To verify someone's employment,

you might ask the personnel office or the director of human resources. And to

check if someone lives at a particular address, you might consult the office of

public records.

Sometimes, a particular person is designated to

attest to the authenticity or validity of a document or person. For example, a

notary public attests to the validity of a (written) signature on a document.

Some companies have a security officer to verify that an employee has

appropriate security clearances to read a document or attend a meeting. Many

companies have a separate personnel office for each site or each plant

location; the personnel officer vouches for the employment status of the

employees at that site. Any of these officers or heads of offices could

credibly sign certificates for people under their purview. Natural hierarchies

exist in society, and these same hierarchies can be used to validate

certificates.

The only problem with a hierarchy is the need

for trust at the top level. The entire chain of authenticity is secure because

each certificate contains the key that decrypts the next certificate, except

for the top. Within a company, it is reasonable to trust the person at the top.

But if certificates are to become widely used in electronic commerce, people

must be able to exchange certificates securely across companies, organizations,

and countries.

The Internet is a large federation of networks

for intercompany, interorganizational, and international (as well as

intracompany, intraorganizational, and intranational) communication. It is not

a part of any government, nor is it a privately owned company. It is governed

by a board called the Internet Society. The Internet Society has power only

because its members, the governments and companies that together make up the

Internet, agree to work together. But there really is no "top" for

the Internet. Different companies, such as C&W HKT, SecureNet, Verisign,

Baltimore Technologies, Deutsche Telecom, Societá Interbancaria per l'Automatzione

di Milano, Entrust, and Certiposte are root certification authorities, which

means each is a highest authority that signs certificates. So, instead of one

root and one top, there are many roots, largely structured around national

boundaries.

In this chapter, we introduced several

approaches to key distribution, ranging from direct exchange to distribution

through a central distribution facility to certified advance distribution. We

explore the notions of certificates and certificate authorities in more depth

in Chapter 7,

in which we discuss Public Key Infrastructures. But no matter what approach is

taken to key distribution, each has its advantages and disadvantages. Points to keep in mind about

any key distribution protocol include the following:

· What operational restrictions are there? For

example, does the protocol require a continuously available facility, such as

the key distribution center?

·

What trust requirements are there? Who and what entities must be

trusted to act properly?

·

What is the protection against failure? Can an outsider impersonate

any of the entities in the protocol and subvert security? Can any party of the

protocol cheat without detection?

·

How efficient is the protocol? A protocol requiring several steps

to establish an encryption key that will be used many times is one thing; it is

quite another to go through several time-consuming steps for a one-time use.

·

How easy is the protocol to implement? Notice that complexity in

computer implementation may be different from manual use.

The descriptions of the protocols have raised

some of these issues; others are brought out in the exercises at the end of

this chapter.

Related Topics