Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Coronary Vascular Disorders

Surgical Procedures - Invasive Coronary Artery Procedures

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Coronary Artery Revascularization

Advances

in diagnostics, medical management, surgical and anes-thesia techniques, and

cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), as well as the care provided in critical care and

surgical units, home care, and rehabilitation programs, have helped make

surgery a viable treatment option for patients with cardiac disease. CAD has

been treated by some form of myocardial revascularization since the 1960s; the

most common CABG techniques have been per-formed for approximately 35 years.

CABG is a surgical procedure in which a blood vessel from another part of the

body is grafted to the occluded coronary artery so that blood can flow beyond

the occlusion; it is also called a bypass

graft.

Candidates

for CABG are usually patients with the following conditions (Eagle et al.,

1999):

·

Angina that cannot be controlled by

medical therapies

·

Unstable angina

·

A positive exercise tolerance test

and lesions or blockage that cannot be treated by PCI

·

A left main coronary artery lesion

or blockage of more than 60%

·

Blockage of two or three coronary

arteries, one of which is the proximal left anterior descending artery

·

Left ventricular dysfunction with

blockages in two or more coronary arteries

·

Complications from or unsuccessful

PCIs

For

a patient to be considered for CABG, the coronary arter-ies to be bypassed must

have at least a 70% occlusion (60% if it is the left main coronary artery). If

the lesion involves less than 70% of the artery, enough blood can flow through

the blocked artery to prevent adequate blood flow through the bypass graft. As

a result, the graft would clot, effectively negating the surgery.

The

vessel most commonly used for CABG is the greater saphe-nous vein, followed by

the lesser saphenous vein (Fig. 28-7). Cephalic and basilic veins are used

also. The vein is removed from the leg (or arm) and grafted to the ascending

aorta and to the coronary artery distal to the lesion. The saphenous veins are

used in emergency CABG procedures because they can be obtained by one surgical

team while another team performs the chest surgery. One side effect of using a

large vein is edema, which may develop in the extremity from which it was

taken. The degree of edema varies and may diminish over time. Approximately 5

to 10 years after CABG, symptomatic atherosclerotic changes develop in

saphenous veins used for grafting. In arm veins, the same changes develop more

quickly, approximately 3 to 6 years after the surgery.

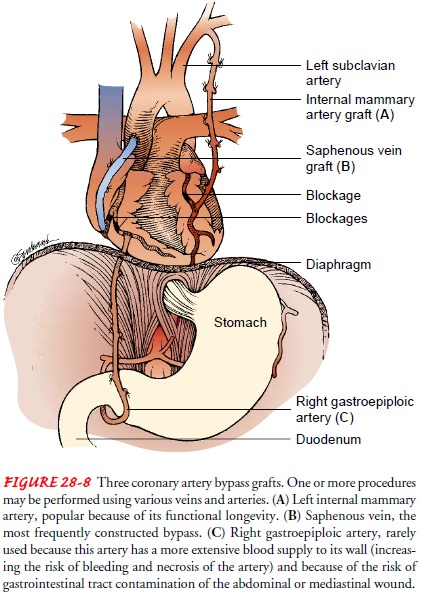

The

right and left internal mammary arteries and, occasion-ally, radial arteries

are also used for CABG. Arterial grafts are pre-ferred to vein grafts because

they do not develop atherosclerotic changes as quickly and remain patent

longer. In general, the sur-geon leaves the proximal end of the mammary artery

intact and detaches the distal end of the artery from the chest wall. This

dis-tal end of the artery is then grafted to the coronary artery distal to the

occlusion. Disadvantages of using the internal mammary arteries are that they

may not be long enough or wide enough for the bypass and ulnar nerve damage may

result.

The gastroepiploic artery (located along the greater curvature of the stomach) may also be used, although it does not respond as well when used as a graft. It has a more extensive blood supply to its wall than the internal mammary arteries, making dissection from the stomach difficult and increasing the potential for injury and ischemia of the graft.

Use of the gastroepiploic artery requires the surgeon to

extend the chest incision to the abdomen, thereby exposing the patient to the

additional risks of an abdominal inci-sion and infection at the surgical site

from contamination by the gastrointestinal tract.

TRADITIONAL CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFT

The

traditional CABG procedure is performed with the patient under general

anesthesia. Usually, the surgeon makes a median sternotomy incision and

connects the patient to the CPB ma-chine. Next, a blood vessel from another

part of the patient’s body (eg, saphenous vein, left internal mammary artery)

is grafted distal to the coronary artery lesion, bypassing the obstruction

(Fig. 28-8). CPB is then discontinued and the incision is closed. The patient

then is admitted to a critical care unit.

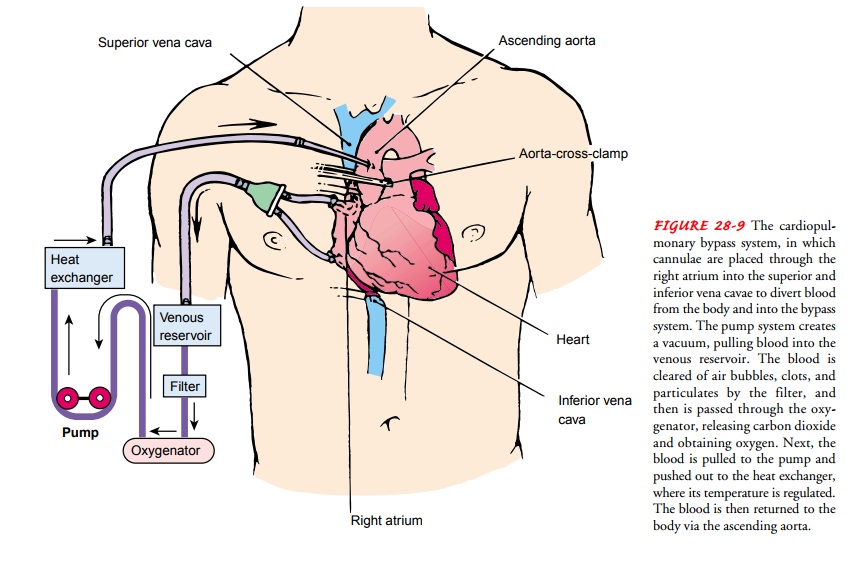

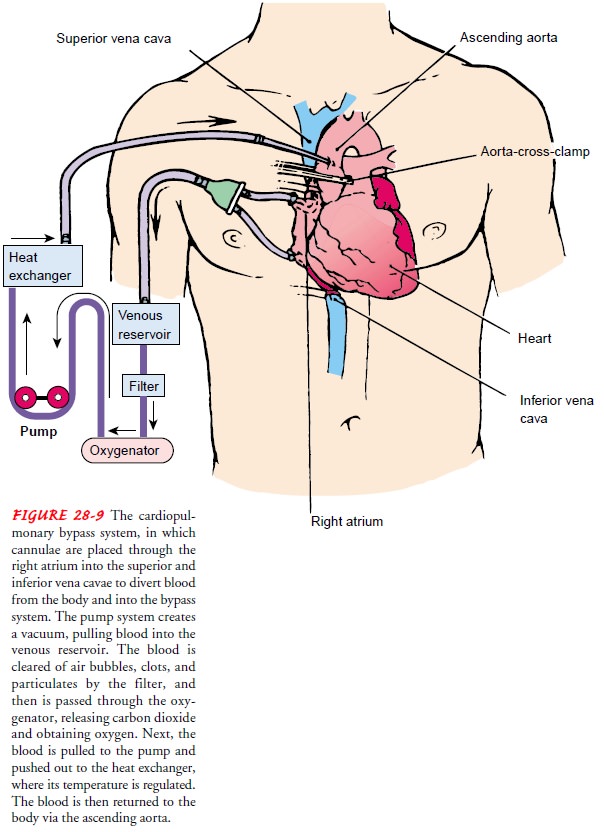

Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB).

Many cardiac surgical proce-dures are possible because of CPB (ie,

extracorporeal circulation). The procedure mechanically circulates and

oxygenates blood for the body while bypassing the heart and lungs. CPB uses a

heart-lung machine to maintain perfusion to other body organs and tis-sues

while the surgeon works in a bloodless surgical field.

CPB, a common but complex technique, is accomplished by placing a cannula in the right atrium, vena cava, or femoral veinto withdraw blood from the body.

The cannula is connected to tubing filled with an

isotonic crystalloid solution (usually 5% dex-trose in lactated Ringer’s

solution). Venous blood removed from the body by the cannula is filtered,

oxygenated, cooled or warmed, and then returned to the body. The cannula used

to return the oxygenated blood is usually inserted in the ascending aorta, but

it may be inserted in the femoral artery (Fig. 28-9).

The

patient receives heparin, an anticoagulant, to prevent thrombus formation and

possible embolization that may occur when blood contacts the foreign surfaces

of the CPB circuit and is pumped into the body by a mechanical pump (not the

normal blood vessels and heart). After the patient is disconnected from the

bypass machine, protamine sulfate is administered to reverse the effects of

heparin.

During

the procedure, hypothermia is maintained, usually 28°C to 32°C (82.4°F to 89.6°F). The

blood is cooled during CPB and returned to the body. The cooled blood slows the

body’s basal metabolic rate, thereby decreasing its demand for oxygen. Cooled

blood usually has a higher viscosity, but the crys-talloid solution used to

prime the bypass tubing dilutes the blood. When the surgical procedure is

completed, the blood is rewarmed as it passes through the CPB circuit. Urine

output, blood pres-sure, arterial blood gas measurements, electrolytes,

coagulation studies, and the ECG are monitored to assess the patient’s status

during CPB.

MINIMALLY INVASIVE DIRECT CABG (MIDCAB)

For patients with single coronary artery blockages who cannot be treated by PTCA or with contraindications for CPB, an alter-native to traditional CABG is minimally invasive direct CABG (MIDCAB). With the patient under general anesthesia, the sur-geon makes one or more 2- to 4-inch (5- to 10-cm) incisions in the chest wall for a left or right anterior thoracotomy or for a mid-sternal or midline upper laparotomy.

The graft is prepared for the bypass (see previous

graft selection description). The surgeon identifies the location of the

coronary artery for the CAB, and a special instrument, a myocardial stabilizer,

is put around the site. The stabilizer holds the graft site still for the

surgeon while the heart continues to beat. Other techniques to minimize

movement of the beating heart are to temporarily collapse the lung on the side

of the chest where the surgery is being performed, decrease the respiratory

rate and the volume of each breath, and give med-ications to cause bradycardia

or up to 20 seconds of asystole.

Patients

treated with MIDCAB may recover from anesthesia in the postanesthesia care unit

(PACU) and then be admitted to a telemetry unit for 1 to 3 days. Nursing care

is often directed to-ward routine postoperative pulmonary interventions

(especially if a lung was collapsed during the MIDCAB) and incisional pain

management (especially if a thoracotomy incision was made).

PORT ACCESS CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFT

Port

access CABG is another alternative to traditional CABG. With the patient under

general anesthesia, the surgeon makes three or more incisions (ports) to

perform the CABG. One 0.5-to 1-inch (1.3- to 2.5-cm) incision in the groin

provides access to a femoral artery and vein. The femoral artery is used for a

multi-purpose catheter threaded retrograde through the aorta to the as-cending

aorta. The catheter is used to return blood from CPB to the patient, to occlude

the aorta by inflating a balloon near the end of the catheter, to provide a

cardioplegia solution to the coronary arteries, and to vent air from the aortic

root during the surgical pro-cedure. The femoral vein is used for a catheter

threaded through the vena cava to the right atrium to drain blood from the

patient for CPB. Another 0.5- to 1-inch (1.3- to 2.5-cm) incision in the neck

provides access to the jugular vein for two catheters. One catheter is threaded

into the pulmonary artery to remove air, fluid, and blood that may enter the

right heart during surgery. The other catheter is threaded into the right

atrium and the tip posi-tioned in the coronary sinus for retrograde infusion of

the car-dioplegia solution. One or more thoracotomy incisions, usually 2 to 3.5

inches (5 to 9 cm) long, are made for insertion of the sur-gical instruments.

One of the thoracotomy ports may be used for video-assisted imaging equipment.

CPB

is begun when the equipment is in place through the groin, neck, and thoracotomy

incisions. The balloon on the aortic catheter is inflated, and the cardioplegia

solution is injected into the coro-nary arteries. Cardioplegia solution is a

crystalloid and electrolyte liquid used to stop the heart and protect the

myocardium during cardiac surgical procedures. One lung may be temporarily

col-lapsed to assist with exposing the surgical site. The CABG is per-formed

through a thoracotomy incision. When the CABG is complete, air is vented from

the pulmonary artery and aorta. The balloon on the aortic catheter is deflated,

and CPB is discontinued. The surgical instruments and the catheters are

removed. The inci-sions are closed. The patient’s postoperative care is similar

to that after traditional CABG.

COMBINATION PERCUTANEOUS TRANSLUMINAL CORONARY ANGIOPLASTY AND CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFT

Patients

who have blockages in the left anterior descending and at least one other

coronary artery who are not candidates for tradi-tional CABG or prefer less

invasive procedures may be treated with both MIDCAB and PTCA. Because patients

need their blood to be able to clot after MIDCAB, but require anticoagulation

after PTCA, the sequence and timing of providing both treatments to the same

patient are being investigated.

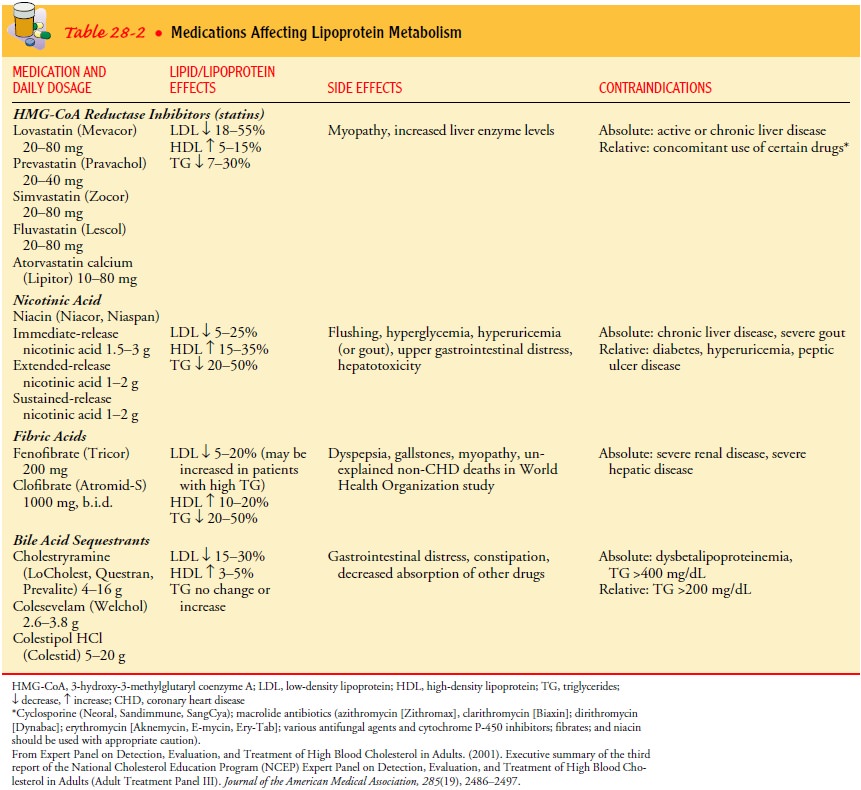

COMPLICATIONS

CABG

may result in complications such as MI, dysrhythmias, and hemorrhage (see Table

28-2;. The patient’s underlying heart disease remains, and angina, exercise

intolerance, or other symptoms experienced be-fore CABG may develop again.

Medications required before surgery may need to be continued. Lifestyle

modifications rec-ommended before surgery remain important to treat the

under-lying CAD and for the continued viability of the newly implanted grafts.

Related Topics