Chapter: Medical Physiology: Pregnancy and Lactation

Response of the MotherŌĆÖs Body to Pregnancy

Response of the MotherŌĆÖs Body to Pregnancy

Most apparent among the many reactions of the mother to the fetus and to the excessive hormones of pregnancy is the increased size of the various sexual organs. For instance, the uterus increases from about 50 grams to 1100 grams, and the breasts approximately double in size. At the same time, the vagina enlarges and the introitus opens more widely. Also, the various hormones can cause marked changes in a pregnant womanŌĆÖs appearance, sometimes resulting in the development of edema, acne, and masculine or acromegalic features.

Weight Gain in the Pregnant Woman

The average weight gain during pregnancy is about 24 pounds, with most of this gain occurring during the last two trimesters. Of this, about 7 pounds is fetus and 4 pounds is amniotic fluid, placenta, and fetal membranes. The uterus increases about 2 pounds and the breasts another 2 pounds, still leaving an average weight increase of 9 pounds. About 6 pounds of this is extra fluid in the blood and extracellular fluid, and the remaining 3 pounds is generally fat accumulation. The extra fluid is excreted in the urine during the first few days after birth, that is, after loss of the fluid-retaining hormones from the placenta.

During pregnancy, a woman often has a greatly increased desire for food, partly as a result of removal of food substrates from the motherŌĆÖs blood by the fetus and partly because of hormonal factors. Without appro-priate prenatal control of diet, the motherŌĆÖs weight gain can be as great as 75 pounds instead of the usual 24 pounds.

Metabolism During Pregnancy

As a consequence of the increased secretion of many hormones during pregnancy, including thyroxine, adrenocortical hormones, and the sex hormones, the basal metabolic rate of the pregnant woman increases about 15 per cent during the latter half of pregnancy. As a result, she frequently has sensations of becoming over-heated. Also, owing to the extra load that she is carry-ing, greater amounts of energy than normal must be expended for muscle activity.

Nutrition During Pregnancy. By far the greatest growth ofthe fetus occurs during the last trimester of pregnancy; its weight almost doubles during the last 2 months of pregnancy. Ordinarily, the mother does not absorb suf-ficient protein, calcium, phosphates, and iron from her diet during the last months of pregnancy to supply these extra needs of the fetus. However, anticipating these extra needs, the motherŌĆÖs body has already been storing these substancesŌĆösome in the placenta, but most in the normal storage depots of the mother.

If appropriate nutritional elements are not present in a pregnant womanŌĆÖs diet, a number of maternal defi-ciencies can occur, especially in calcium, phosphates, iron, and the vitamins. For example, about 375 mil-ligrams of iron is needed by the fetus to form its blood, and an additional 600 milligrams is needed by the mother to form her own extra blood. The normal store of nonhemoglobin iron in the mother at the outset of pregnancy is often only 100 milligrams and almost never more than 700 milligrams. Therefore, without sufficient iron in her food, a pregnant woman usually develops hypochromic anemia. Also, it is especially importantthat she receive vitamin D, because although the total quantity of calcium used by the fetus is small, calcium is normally poorly absorbed by the motherŌĆÖs gastroin-testinal tract without vitamin D. Finally, shortly before birth of the baby, vitamin K is often added to the motherŌĆÖs diet so that the baby will have sufficient pro-thrombin to prevent hemorrhage, particularly brain hemorrhage, caused by the birth process.

Changes in the Maternal Circulatory System During Pregnancy

Blood Flow Through the Placenta, and Cardiac Output During Pregnancy. About 625 milliliters of blood flows throughthe maternal circulation of the placenta each minute during the last month of pregnancy. This, plus the general increase in the motherŌĆÖs metabolism, increases the motherŌĆÖs cardiac output to 30 to 40 per cent above normal by the 27th week of pregnancy; then, for reasons unexplained, the cardiac output falls to only a little above normal during the last 8 weeks of pregnancy, despite the high uterine blood flow.

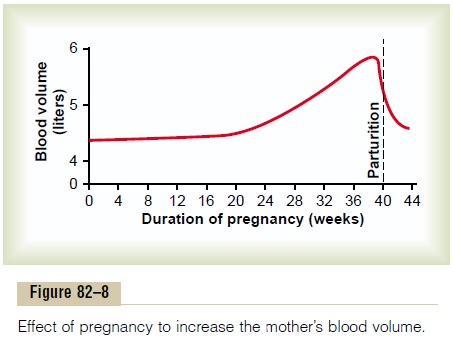

Blood Volume During Pregnancy

The maternal bloodvolume shortly before term is about 30 per cent above normal. This increase occurs mainly during the latter half of pregnancy, as shown by the curve of Figure 82ŌĆō8. The cause of the increased volume is likely due, at least in part, to aldosterone and estrogens, which are greatly increased in pregnancy, and to increased fluid retention by the kidneys. Also, the bone marrow becomes increas-ingly active and produces extra red blood cells to go with the excess fluid volume. Therefore, at the time of birth of the baby, the mother has about 1 to 2 liters of extra blood in her circulatory system. Only about one fourth of this amount is normally lost through bleeding during delivery of the baby, thereby allowing a consid-erable safety factor for the mother.

Maternal Respiration During Pregnancy

Because of the increased basal metabolic rate of a preg-nant woman and because of her greater size, the total amount of oxygen used by the mother shortly before birth of the baby is about 20 per cent above normal, and a commensurate amount of carbon dioxide is formed.

These effects cause the motherŌĆÖs minute ventilation to increase. It is also believed that the high levels of prog-esterone during pregnancy increase the minute ventila-tion even more, because progesterone increases the respiratory centerŌĆÖs sensitivity to carbon dioxide. The net result is an increase in minute ventilation of about 50 per cent and a decrease in arterial PCO2 to several millimeters of mercury below that in a nonpregnant woman. Simultaneously, the growing uterus presses upward against the abdominal contents, and these press upward against the diaphragm, so that the total excur-sion of the diaphragm is decreased. Consequently, the respiratory rate is increased to maintain the extra ventilation.

Function of the Maternal Urinary System During Pregnancy

The rate of urine formation by a pregnant woman is usually slightly increased because of increased fluid intake and increased load or excretory products. But in addition, several special alterations of urinary function occur.

First, the renal tubulesŌĆÖ reabsorptive capacity for sodium, chloride, and water is increased as much as 50 per cent as a consequence of increased production of steroid hormones by the placenta and adrenal cortex.

Second, the glomerular filtration rate increases as much as 50 per cent during pregnancy, which tends to increase the rate of water and electrolyte excretion in the urine. When all these effects are considered, the normal pregnant woman ordinarily accumulates onlyabout 6 pounds of extra water and salt.

Amniotic Fluid and Its Formation

Normally, the volume of amniotic fluid (the fluid inside the uterus in which the fetus floats) is between 500 mil-liliters and 1 liter, but it can be only a few milliliters or as much as several liters. Isotope studies of the rate of formation of amniotic fluid show that, on average, the water in amniotic fluid is replaced once every 3 hours, and the electrolytes sodium and potassium are replaced an average of once every 15 hours. A large portion of the fluid is derived from renal excretion by the fetus. Likewise, a certain amount of absorption occurs by way of the gastrointestinal tract and lungs of the fetus. However, even after in utero death of a fetus, some turnover of the amniotic fluid is still present, which indi-cates that some of the fluid is formed and absorbed directly through the amniotic membranes.

Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

About 5 per cent of all pregnant women experience a rapid rise in arterial blood pressure to hypertensive levels during the last few months of pregnancy. This is also associated with leakage of large amounts of protein into the urine. This condition is called preeclampsia or toxemia of pregnancy. It is often characterized by excesssalt and water retention by the motherŌĆÖs kidneys and by weight gain and development of edema and hyperten-sion in the mother. In addition, there is impaired func-tion of the vascular endothelium, and arterial spasm occurs in many parts of the motherŌĆÖs body, most sig-nificantly in the kidneys, brain, and liver. Both the renal blood flow and the glomerular filtration rate are decreased, which is exactly opposite to the changes that occur in the normal pregnant woman. The renal effects also include thickened glomerular tufts that contain a protein deposit in the basement membranes.

Various attempts have been made to prove that preeclampsia is caused by excessive secretion of pla-cental or adrenal hormones, but proof of a hormonal basis is still lacking. Another theory is that preeclamp-sia results from some type of autoimmunity or allergy in the mother caused by the presence of the fetus. In support of this, the acute symptoms usually disappear within a few days after birth of the baby. There is also evidence that preeclampsia is initiated by insufficientblood supply to the placenta, resulting in the placentaŌĆÖsrelease of substances that cause widespread dysfunction of the maternal vascular endothelium. During normal placental development, the trophoblasts invade the arterioles of the uterine endometrium and completely remodel the maternal arterioles into large blood vessels with low resistance to blood flow. In patients with preeclampsia, the maternal arterioles fail to undergo these adaptive changes, for reasons that are still unclear, and there is insufficient blood supply to the placenta. This, in turn, causes the placenta to release various sub-stances that enter the motherŌĆÖs circulation and cause impaired vascular endothelial function, decreased blood flow to the kidneys, excess salt and water retention, and increased blood pressure. Although the factors that link reduced placental blood supply with maternal endothe-lial dysfunction are still uncertain, some experimental studies suggest a role for increased levels of inflamma-tory cytokines such astumor necrosis factor-a and interleukin-6.

Eclampsia is an extreme degree of preeclampsia,characterized by vascular spasm throughout the body; clonic seizures in the mother, sometimes followed by coma; greatly decreased kidney output; malfunction of the liver; often extreme hypertension; and a generalized toxic condition of the body. It usually occurs shortly before birth of the baby. Without treatment, a high per-centage of eclamptic mothers die. However, with optimal and immediate use of rapidly acting vasodilating drugs to reduce the arterial pressure to normal, followed by immediate termination of pregnancyŌĆöby cesarean section if necessaryŌĆöthe mortality even in eclamptic mothers has been reduced to 1 per cent or less.

Related Topics