Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Psychotic Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition

Psychotic Disorder Due to a

General Medical Condition

Definition

A psychotic disorder due to a general medical

condition is char-acterized clinically by hallucinations or delusions occurring

in a clear sensorium, without any associated decrement in intellectual

abilities. Furthermore, one must be able to demonstrate, by his-tory, physical

examination or laboratory findings, that the psy-chosis is occurring on the

basis of a general medical disorder.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Of all the causes of psychosis, the most commonly

encountered are three primary psychiatric disorders, namely, schizophrenia,

schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder, each of these being covered

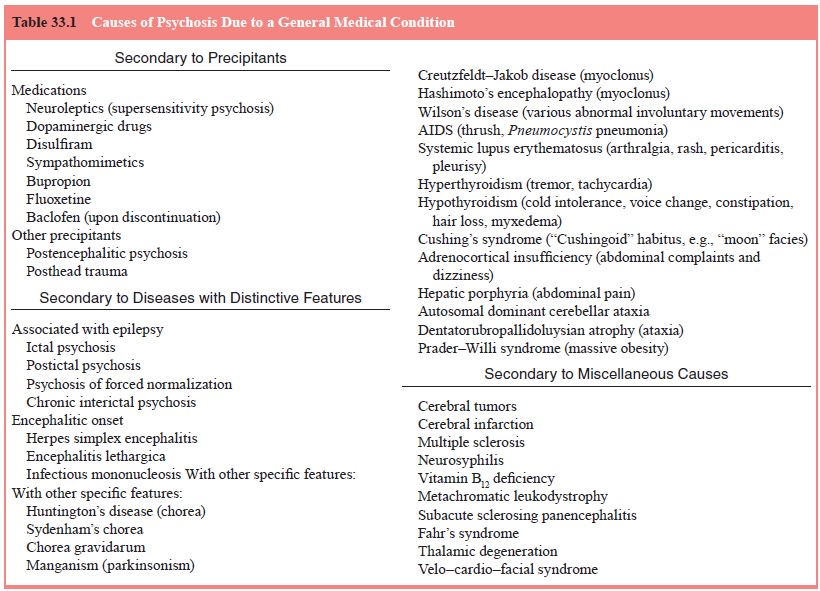

elsewhere in this text. Table 33.1 lists the various secondary causes of

psychosis dividing them into those occur-ring secondary to precipitants (e.g., medications), those occur-ring secondary to diseases with distinctive

features (e.g., the chorea of Huntington’s disease) and finally a group

occurring secondary to miscellaneous

causes (e.g., cerebral tumors).

Psychosis occurring secondary to precipitants is per-haps the most common form of

secondary psychosis. Among the various possible precipitants, substances, that

is to say, drugs of abuse, are perhaps the most common,

hallucinogens, phencyclidine, cannabis and alcohol. After drugs of abuse, various medications are the next most common precipitants, and of the medications listed in Table 33.1, the most problematic are the neuroleptics themselves. It appears that in a very small minority of patients treated chroni-cally with neuroleptics, a “supersensitivity psychosis” (or, as it has also been called, on analogy with tardive dyskinesia, “tardive psychosis”) may occur. Making such a diagnosis in the case of patients with schizophrenia may be difficult, as one may well say that any increase in psychotic symptoms, rather than evidence for a supersensitivity psychosis, may merely represent an exac-erbation of the schizophrenia; in the case of patients treated with antipsychotics for other conditions (e.g. Tourette’s syndrome), however, the appearance of a psychosis is far more suggestive, as it could not be accounted for on the basis of the disease for which the neuroleptic was prescribed. Dopaminergic drugs capable of causing a psychosis include levodopa itself, and such direct-acting dopamine agonists as bromocriptine and lergotrile. The other medications noted in Table 33.1 only very rarely cause a psychosis.

Of the various encephalitidies which may have a psycho-sis

as a sequela, the most classic is encephalitis lethargica (von Economo’s

disease), a disease which, though no longer occurring in epidemic form, may

still be seen sporadically.

Of the psychoses secondary to diseases with distinctive features, the psychoses of epilepsy are by far the most important, and these may be ictal, postictal, or

interictal. Ictal psychoses represent complex partial seizures and are

immediately sug-gested by their exquisitely paroxysmal onset. Postictal

psycho-ses are typically preceded by a “flurry” of grand mal or complex partial

seizures and, importantly, are separated from the last of this “flurry” of

seizures by a “lucid” interval lasting from hours to days. Interictal psychoses

appear in one of two forms, namely, the psychosis of forced normalization and

the chronic interictal psychosis. The psychosis of forced normalization appears

when anticonvulsants have not only stopped seizures but have essen-tially

“normalized” the EEG: a disappearance of the psychosis with the resumption of

seizure activity secures the diagnosis. The chronic interictal psychosis, often

characterized by delusions of persecution and reference and auditory

hallucinations, appears subacutely, over weeks or months, in patients with

longstanding, uncontrolled grand mal or complex partial seizures.

Encephalitic psychoses are suggested by such

typical “en-cephalitic” features such as headache, lethargy and fever.

Promptdiagnosis is critical, especially in the case of herpes simplex

en-cephalitis, given its treatability.

The other specific features listed in Table 33.1

are fairly straightforward. In the past, the differential between Hunting-ton’s

disease and schizophrenia complicated by tardive dyski-nesia was difficult;

today, the availability of genetic testing has greatly simplified this

diagnostic task.

Of the miscellaneous causes capable of causing psychosis, cerebral tumors are perhaps the most important, with psychosis being noted with tumors of the frontal lobe, corpus callosum and temporal lobe. Suggestive clinical evidence for such a cause in-cludes prominent headache, seizures, or certain focal signs, such as aphasia. Cerebral infarction is likewise an important cause, and is suggested not only by accompanying focal signs, but also by its acute onset: infarction of the frontal lobe, temporo-parietal and thalamus have all been implicated. Neurosyphilis should never be forgotten as a differential possibility in cases of psychosis of obscure origin, and an FTA (Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody) is appropriate in such cases. Vitamin B12 deficiency, likewise, should be borne in mind, especially as this may present with psychosis without any evidence of spinal cord or hematologic involvement. The remaining disorders listed in Table 33.1 are extremely rare causes of psychosis, and represent the “zebras” of this differential listing. Among these “zebras”, however, one is of particular interest, namely velo–cardio–facial syndrome. This genetic disorder, characterized by cleft palate, cardiovas-cular malformations and dysmorphic facies (micrognathia and prominent nose), and, often, mental retardation, also appears, in a substantial minority of cases, to cause a psychosis phenotypi-cally very similar to that caused by schizophrenia.

Related Topics