Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Klüver–Bucy Syndrome

Klüver–Bucy Syndrome

Definition

In 1939, KlĂĽver and Bucy (1939) noted some striking

behavio-ral changes in monkeys which had been subjected to bilateratemporal

lobectomy, and in so doing described the syndrome that now bears their names.

The full syndrome is characterized by hypermetamorphosis (excessive tendency to

take notice and attend and react to every visual stimulus), agnosia,

hyperorality, emotional placidity and hypersexuality. Some examples of the

syndrome in humans follow.

The first example demonstrates hypersexuality,

hyperoral-ity, agnosia and emotional placidity. The patient was a 31-year-old

woman, who, after recovering from a herpes simplex encephali-tis, “made

inappropriate sexual advances to female attendants, both manually and orally.

At home, she was constantly chew-ing and swallowing, and all objects within

reach were placed in her mouth…including toilet paper and faeces…Her affect was

characterized by passivity and a pet-like compliance with those attending her”

(Lilly et al., 1983).

The second example provides examples of

hypermeta-morphosis, hyperorality, agnosia and hypersexuality. The pa-tient, a

58-year-old man who had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease for 6 years, “spent

much of his time examining ordinary objects such as the doorstep, ashtrays, or

spots on the floor. He placed many objects in his mouth and occasionally ate

soil from plant containers … he rubbed his genitals so frequently that he

developed an excoriation on the shaft of his penis” (Lilly et al., 1983).

Finally, there is the case of a 46-year-old man,

who, during a complex partial seizure, “was observed grabbing for objects on

his bedside table, and he masturbated in front of the nurs-ing staff. He also

placed objects in his mouth, chewed on tissue paper, and attempted to drink

from his urine container” (Nakada et al.,

1984). Here, there are hypermetamorphosis, hypersexual-ity, hyperorality and

agnosia

Etiology and Pathophysiology

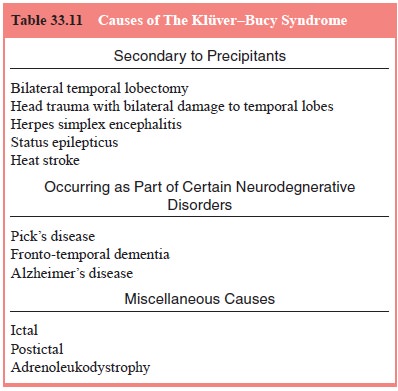

The various causes of the Klüver–Bucy syndrome are

listed in Table 33.11: in each case, bilateral damage or dysfunction of the

temporal lobes has occurred. The mechanism of such bilateral damage in the case

of precipitants is fairly straightforward. The neurodegenerative disorders

listed have a predilection for the temporal lobes, and this is particularly the

case in Pick’s dis-

cause; in some cases, the syndrome itself may ease

and fronto-temporal dementia. Indeed, the appearance of the Klüver–Bucy

syndrome early in the course of a dementia is a significant diagnostic clue to

one of these two disorders; in the case of Alzheimer’s disease, the syndrome,

if it does occur, is generally seen only late in the course. Of the

miscellaneous causes, an ictal Klüver–Bucy syndrome is suggested by its

exqui-sitely paroxysmal onset and by the occurrence of other symptoms typical

for a complex partial seizure, such as confusion, and a postictal Klüver–Bucy

syndrome by the history of an immedi-ately preceding generalized seizure.

Adrenoleukodystrophy, the last in the list, is an extremely rare cause of the

Klüver–Bucy syndrome.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

The combination of hyperorality and hypersexuality

often brings the patient to medical attention: although the full syndrome

presents little diagnostic difficulty, as it is not mimicked by any other

condition, partial syndromes, consisting primarily of hy-permetamorphosis and

hypersexuality, may suggest mania. The differential rests on the presence or

absence of pressured speech and activity, findings typical of mania but absent

in the Klüver– Bucy syndrome.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

The full Klüver–Bucy syndrome is, overall, rare; in

dementia clinics, however, full or partial Klüver–Bucy syndromes are commonly

seen.

Course

The course depends on the underlying have a fatal

outcome.

Treatment

The underlying cause, if possible, is treated. In

chronic cases, neuroleptics have been reported to be helpful; there are,

however, no controlled studies.

Related Topics