Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Mood Disorder with Manic Features

Mood Disorder with Manic Features

Definition

Mood disorder due to a general medical condition

with manic features is characterized by a prominent and persistently ele-vated,

expansive or irritable mood which, on the basis of the his-tory, physical or

laboratory examinations can be attributed to an underlying general medical condition.

Other manic symptoms, such as increased energy, decreased need for sleep,

hyperactivity, distractibility, pressured speech and flight of ideas, may or

may not be present.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The vast majority of cases of sustained, elevated

or irritable mood occur as part of four primary disorders, namely bipolar I

disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder and schizoaf-fective

disorder (bipolar type). Cases of elevated or irritable mood secondary to other

causes (e.g., secondary to treatment with corticosteroids) are much less

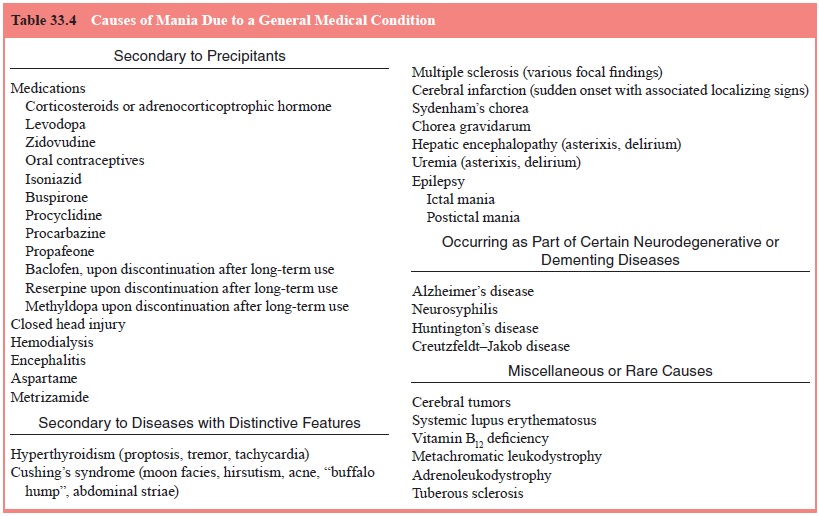

common. Table 33.4 lists sec-ondary causes of elevated or irritable mood, with

these causes divided into categories designed to facilitate the task of

differ-ential diagnosis.

In utilizing Table 33.4, the first step is to

determine whether the mania could be secondary

to precipitants. Sub-stance-induced mood disorder related to drugs of abuse

is covered in the relevant substance-related disorders. Of the precipitating

factors listed in Table 33.4, medications are the most common offenders.

Before, however, attributing the mania to one of these medications, it is

critical to demonstrate that the mania occurred only after initiation of that

medication; ideally, one would also want to show that themania spontaneously

resolved subsequent to the medication’s discontinuation. Of the medications

listed, corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are likely to cause mania, with

the likelihood in-creasing in direct proportion to dose: in one study

(Wolkow-itz et al., 1990), 80 mg of

prednisone produced mania within five days in 75% of subjects. Levodopa is the

next most likely cause, and in the case of levodopa the induced mania may be so

pleasurable that some patients have ended up abusing the drug (Giovannoni et al., 2000). Anabolic steroid abuse

may cause an irritable mania, and such a syndrome occurring in a “bulked up”

patients should prompt a search for other clinical evidence of abuse, such as

gynecomastia and testicular atrophy. Closed head injury may be followed by mania

either directly upon emergence from postcoma delirium, or after an interval of

months. Hemodialysis may cause mania, and in one case (Jack et al., 1983) mania occurred as the

presenting sign of an even-tual dialysis dementia. Encephalitis may cause mania,

as, for example, in postinfectious encephalomyelitis, with the correct

diagnosis eventually being suggested by more typical signs such as delirium or

seizures. Encephalitis lethargica (Von Economo’s disease; European Sleeping

Sickness) may also be at fault, with the diagnosis suggested by classic signs

such as sleep reversal or oculomotor paralyses.

Mania occurring secondary to disease with distinctive features is immediately suggested by these features, as listed in Table 33.4. Some elaboration may be

in order regarding ma-nia secondary to cerebral infarction. This cause, of

course, is suggested by the sudden onset of the clinical disturbance, with the

mania being accompanied by various other more or less localizing signs: what is

most remarkable here is the variety of structures which, if infarcted, may be

followed by mania

Thus, mania has been noted with infarction of the

midbrain, thalamus (either on the right side or bilaterally, anterior limb of

the internal capsule and adjacent caudate on the right, and subcortical white

matter or cortical infarction on the right in the frontoparietal or temporal

areas. Mania associated with epilepsy may also deserve additional comment.

Ictal mania is characterized by its paroxysmal onset, over seconds and the diagnosis

of postictal mania is suggested when mania oc-curs shortly after a “flurry” of

grand mal or complex partial seizures.

Mania occurring

as part of certain neurodegenerative or

dementing diseases is suggested, in general, by a concur-rent dementia, and

in most cases the mania plays only a minor role in the overall clinical

pictures. Neurosyphilis, however, is an exception to this rule, for in patients

with general paresis of the insane (dementia paralytica) mania may dominate the

picture.

Of the miscellaneous

or rare causes of mania, cerebral tumors are the most important to keep in

mind, with mania be-ing noted with tumors of the midbrain, tumors compressing

the hypothalamus, e.g., a craniopharyngioma or a pituitary adenoma, and tumors

of the right thalamus, right cingulate gyrus or one or both frontal lobes.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

In most cases of mania secondary to precipitants, the cause (e.g., treatment with high

dose prednisone) is fairly straightforward; in cases secondary to diseases with distinctive features or occurring as

part of certain neurodegenerative or dementing diseases, the cause is

generally readily discernible if the

clinician is alert to the telltale distinctive features (e.g., a Cushingoid

habitus) and to the presence of dementia indicat-ing one of the dementing

disorders listed in Table 33.4. The miscellaneous

or rare causes represent the “zebras” in the dif-ferential of secondary

mania, and are generally only resorted to when other investigations prove

unrewarding.

As a rule, it is very rare for mania to constitute

the initial presentation of any of the disease or disorders listed in Table

33.4; thus, other evidence of their presence will become evident dur-ing the

routine history and physical examination. Exceptions to the rule include

neurosyphilis, vitamin B12 deficiency and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease,

however in all these cases continued observation will eventually disclose the

appearance of other evi-dence suggestive of the correct diagnosis.

It must always be kept in mind that certain

medications (e.g., antidepressants) may precipitate mania in patients with

bi-polar disorder: in such cases, history will reveal earlier episodes of

either depression, or mania, or both and such cases of mania should not be

considered secondary.

Epidemiology and comorbidity

Relative to cases of primary mania (e.g., bipolar

disorder), sec-ondary mania is relatively rare. In certain settings, however,

sec-ondary mania may be so common as to merit a “top” position on the differential

diagnosis; a prime example would be when prednisone is used in high doses, as

in the treatment of multiple sclerosis or rheumatoid arthritis.

Course

Most cases of medication-induced mania begin to

clear in a mat-ter of days; for other causes, the course of the mania generally

reflects the course of the underlying disease.

Treatment

Treatment, if possible, is directed at the underlying cause. In cases where such etiologic treatment is not possible, or not rapidly ef-fective enough, pharmacologic measures are in order. Mood sta-bilizers, such as lithium or divalproex used in a fashion similar to that for the treatment of mania occurring in bipolar disorder, are commonly used: both lithium and divalproex are effective in the prophylaxis of mania occurring secondary to prednisone; case reports also support the use of lithium for mania secondary to zidovudine and divalproex for mania secondary to closed head injury. As between lithium and divalproex, in cases where there is a risk for seizures (e.g., head injury, encephalitis, stroke or tu-mors), divalproex clearly is preferable

In cases where emergent treatment is required,

before lith-ium or divalproex could have a chance to become effective, oral or

intramuscular lorazepam or haloperidol (in doses of 2 mg and 5 mg,

respectively) may be utilized, again much as in the treat-ment of mania in

bipolar disorder.

Related Topics