Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Mood Disorder with Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms

Mood Disorder with

Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms

Definition

Obsessions consist of unwanted, and generally

anxiety-provoking, thoughts, images or ideas which repeatedly come to mind

despite patients’ attempts to stop them. Allied to this are compulsions, which

consist of anxious urges to do or undo things, urges which, if resisted, are

followed by rapidly increasing anxiety which can often only be relieved by

giving into the compulsion to act. The acts themselves which the patients feel

compelled to perform are often linked to an apprehension on the patients’ part

that they have done something that they ought not to have done or have left

undone something which they ought to have done. Thus, one may feel compelled

repeatedly to subject the hands to washing to be sure that all germs have been

removed, or repeatedly to go back and check on the gas to be sure that it had

been turned off.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

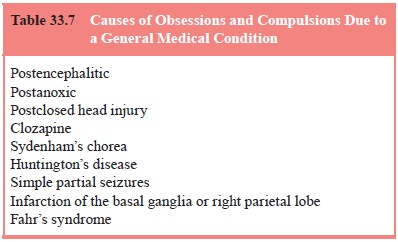

In the vast majority of cases, obsessions and

compulsions oc-cur as part of certain primary psychiatric disorders, including

obsessive–compulsive disorder, depression, schizophrenia and Tourette’s

syndrome. Those rare instances where obsessions and compulsions are secondary

to a general medical condition or medication are listed in Table 33.7.

In most cases, these causes of secondary obsessions

or compulsions are readily discerned, as for example, a history of

encephalitis, anoxia, closed head injury or treatment with clozap-ine.

Sydenham’s chorea is immediately suggested by the appear-ance of chorea,

however, it must be borne in mind that obsessions and compulsions may

constitute the presentation of Sydenham’s chorea, with the appearance of chorea

being delayed for days

(Swedo et al.,

1989). Ictal obsessions or compulsions, constitut-ing the sole clinical

manifestation of a simple partial seizure, may, in themselves, be

indistinguishable from the obsessions and compulsions seen in

obsessive–compulsive disorder, but are sug-gested by a history of other seizure

types, for example, complex partial or grand mal seizures. Infarction of the

basal ganglia or parietal lobe is suggested by the subacute onset of obsessions

or compulsions accompanied by “neighborhood” symptoms such as abnormal

movements or unilateral sensory changes. Fahr’s syn-drome, unlike the

foregoing, may be an elusive diagnosis, only suggested perhaps when CT imaging

incidentally reveals calcifi-cation of the basal ganglia.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Most causes of secondary obsessions and compulsions

are picked up on the routine history and physical examination, with the

pos-sible exception of ictal cases, and here it is critical to make a close

inquiry as to a history of other seizure types: ictal EEGs are not reliable

here, as they are often normal in the case of simple partial seizures. In

doubtful cases a “diagnosis by treatment response” to a trial of an

anticonvulsant may be appropriate.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

As noted earlier, secondary obsessions and

compulsions are rela-tively rare.

Course

Although the course of obsessions and compulsions

due to fixed lesions, such as those seen with head trauma or cerebral

infarc-tion tends to be chronic, some spontaneous recovery may be an-ticipated

over the following months to a year.

Treatment

When treatment of the underlying cause is not

possible, a trial of an SSRI, as used for obsessive–compulsive disorder, might

be appropriate.

Related Topics