Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Personality Change Due to a General Medical Condition

Personality Change Due to a

General Medical Condition

Definition

The personality of an adult represents a coalescence of various personality traits present in childhood and adolescence, and is generally quite enduring and resistant to change. Thus, the ap-pearance of a significant change in an adult’s personality is an ominous clinical sign and indicates the presence of intracranial pathology. Patients themselves may not be aware of the change, however to others, who have known the patient over time, the change is often quite obvious: such observers often note that the patient is “not himself” anymore.

In most cases, the change is nonspecific in nature:

there may be either a gross exaggeration of hitherto minor aspects of the

patient’s personality or the appearance of a personality trait quite

uncharacteristic for the patient. Traits commonly seen in a personality change,

as noted in DSM-IV-TR, include lability, disinhibition, aggressiveness, apathy,

or suspiciousness.

In addition to these nonspecific changes, there are

two specific syndromes which, though not listed in DSM-IV-TR, are

well-described in the literature, namely, the frontal lobe syn-drome and the

interictal personality syndrome (also known as the “Geschwind syndrome”).

The frontal

lobe syndrome is characterized by a variable mixture of disinhibition,

affective changes, perseveration and abulia. Disinhibition manifests with an

overall coarsening of be-havior. Attention to manners and social nuances is

lost: patients may eat with gluttony, make coarse and crude jokes, and may

engage in unwelcome and inappropriate sexual behavior, perhaps by

propositioning much younger individuals or masturbating in public. Affective

changes tend toward a silly, noninfectious euphoria; depression, however, may

also be seen. Perseveration presents with a tendency to persist in whatever

task is currently at hand, and patients may repeatedly button and unbutton

cloth-ing, open and close a drawer or ask the same question again and again.

Abulia is characterized by an absence of desires, urges or interests, and such

patients, being undisturbed by such phenom-ena, may be content to sit placidly

for indefinite periods of time. Importantly, such abulic patients are not

depressed, nor are they incapable of activity: indeed, with active supervision

they may be able to complete tasks; however, once supervision stops, so too do

the patients, as they lapse back into quietude.

The interictal

personality syndrome, a controversial entity (Bear et al., 1982; Rodin and Schmaltz, 1984) is said to occur as a

complication of longstanding uncontrolled epilepsy, with repeated grand mal or

complex partial seizures. The cardi-nal characteristic of this syndrome is what

is known as “viscos-ity”, or, somewhat more colloquially, “stickiness”. Here,

patients seem unable to let go or diverge from the current emotion or train of

thought: existing affects persist long after the situation which occasioned

them, and a given train of thought tends to extend itself indefinitely into a

long-winded and verbose circum-stantiality or tangentiality. This viscosity of

thought may also appear in written expression as patients display

“hypergraphia”, producing long and rambling letters or diaries. The inability

to “let go” may even extend to such simple acts as shaking hands, such that

others may literally have to extract their hand to end the handshake. The

content of the patient’s viscous speech and writing generally also changes, and

tends toward mystical or abstruse philosophical speculations. Finally, there is

also a tendency to hyposexuality, with an overall decrease in libido (Blumer,

1970).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

A personality change is not uncommonly seen as the

prodrome to schizophrenia, however in such cases the eventual appearance of the

typical psychosis will indicate the correct diagnosis.

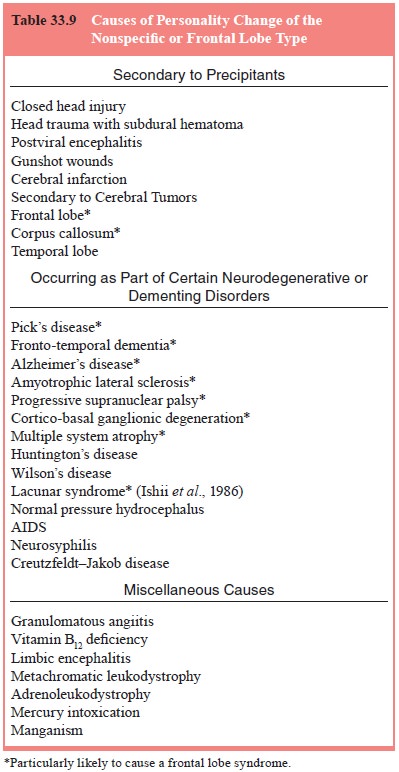

Personality change of the nonspecific or of the

frontal lobe type, as noted in Table 33.9, may occur secondary to precipi-tants (e.g., closed head injury), secondary to cerebral tumors (especially

those of the frontal or temporal lobes) or as

part of certain neurodegenerative or

dementing disorders. Finally, there

is a group of miscellaneous causes.

In Table 33.9, those dis-orders or diseases which are particularly prone to

cause a person-ality change of the frontal lobe type are indicated by an

asterisk. The interictal personality syndrome occurs only in the setting of

chronic repeated grand mal or complex partial seizures, and may represent

microanatomic changes in the limbic system which have been “kindled” by the

repeated seizures (Adamec and Stark-Adamec,1983;Bear,1979)

In the case of personality change occurring secondary to precipitants, the etiology is fairly obvious; an exception might be cerebral infarction, but here

the acute onset and the presence of “neighborhood” symptoms are suggestive. In

ad-dition to infarction of the frontal lobe, personality change has also been

noted with infarction of the caudate nucleus and of the thalamus.

In the case of personality change occurring secondary to precipitants, the etiology is fairly obvious; an exception might be cerebral infarction, but here

the acute onset and the presence of “neighborhood” symptoms are suggestive. In

ad-dition to infarction of the frontal lobe, personality change has also been

noted with infarction of the caudate nucleus and of the thalamus.

Personality change occurring secondary to cerebral tumors

may not be accompanied by any distinctive features, and indeed a personality change may be the only clinical evidence of a

tumor for a prolonged period of time.

Personality change occurring as part of certain neuro-degenerative or dementing disorders deserves

special men-tion, for in many instances the underlying disorder may present

with a personality change; this is particularly the case with Pick’s disease,

fronto-temporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The inclusion of amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis here may be surpris-ing to some, but it is very clear that,

albeit in a small minority cerebral symptoms may not only dominate the early

course of ALS, but may even constitute the presentation of the disease. In the

case of the other neurodegenerative disorders (i.e., progres-sive supranuclear

palsy, cortico–basal ganglionic degeneration, multiple system atrophy,

Huntington’s disease and Wilson’s dis-ease) a personality change, if present,

is typically accompanied by abnormal involuntary movements of one sort or

other, such as parkinsonism, ataxia or chorea. The lacunar syndrome, oc-curring

secondary to multiple lacunar infarctions affecting the thalamus, internal

capsule or basal ganglia, deserves special mention as it very commonly causes a

personality change of the frontal lobe type by interrupting the connections

between the thalamus or basal ganglia and the frontal lobe. Normal pres-sure

hydrocephalus is an important diagnosis to keep in mind, as the condition is

treatable: other suggestive symptoms include a broad-based shuffling gait and

urinary urgency or incontinence. AIDS should be suspected whenever a

personality change is accompanied by clinical phenomena suggestive of immunode-ficiency,

such as thrush. Neurosyphilis may present with a per-sonality change

characterized by slovenliness and disinhibition. Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease may

also present with a personality change, and this appears particularly likely

with the “new vari-ant” type: the eventual appearance of myoclonus suggests the

correct diagnosis.

The miscellaneous

causes represent the diagnostic “ze-bras” in the differential for

personality change. Of them two de-serve comment, given their treatability:

granulomatous angiitis is suggested by prominent headache, and vitamin B12

deficiency by the presence of macrocytosis or a sensory polyneuropathy.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Personality change must be clearly distinguished

from a per-sonality disorder. The personality disorders (e.g., antisocial

personality disorder, borderline personality disorder), all dis-cussed

elsewhere in this book, do not represent a change in the patient’s personality

but rather have been present in a lifelong fashion. In gathering a history on a

patient with a personal-ity change, one finds a more or less distinct time when

the “change” occurred; by contrast, in evaluating a patient with a personality

disorder, one can trace the personality traits in question in a more or less seamless

fashion back into adoles-cence, or earlier.

The frontal lobe syndrome, at times, may present

further diagnostic questions, raising the possibility of either mania, when

euphoria is prominent, or depression, when abulia is at the forefront. Mania is

distinguished by the quality of the euphoria, which tends to be full and

infectious in contrast with the silly, shallow and noninfectious euphoria of

the frontal lobe syndrome. Depression may be distinguished by the quality of

the patients’ experience: depressed patients definitely feel something, whether

it be a depressed mood or simply a weighty sense of oppression. By contrast,

the patient with abulia generally feels nothing: the “mental horizon” is clear

and undisturbed by any dysphoria or unpleasantness.

MRI scanning is diagnostic in most cases: where

this is uninformative, further testing is dictated by one’s clinical

suspi-cions (e.g., HIV testing).

The interictal personality syndrome must be

distin-guished from a personality change occurring secondary to a slowly

growing tumor of the temporal lobe. In some cases, very small tumors, which may

escape detection by routine MRI scanning, may cause epilepsy, and then, with

continued growth, also cause a personality change. Thus, in the case of a

patient with epilepsy who develops a personality change, the diagnosis of the

interictal personality syndrome should not be made until a tumor has been ruled

out by repeat MRI scanning.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

Personality change is common, and is seen with especial

fre-quency after closed head injury and as a prodrome to the de-mentia

occurring with such neurodegenerative disorders as Pick’s disease,

fronto-temporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Course

This is determined by the underlying cause; in the

case of the interictal personality syndrome it appears that symptoms persist

even if seizure control is obtained.

Treatment

Treatment, if possible, is directed at the

underlying cause. Mood stabilizers (i.e., lithium, carbamazepine or divalproex)

may be helpful for lability, impulsivity and irritability; propranoalol, in

high dose, may also have some effect on irritability. Neurolep-tics (e.g.,

olanzapine, risperidone, haloperidol) may be helpful when suspiciousness or

disinhibition are prominent. Antide-pressants (e.g., an SSRI) may relieve

depressive symptoms. Regardless of which agent is chosen, it is prudent, given

the general medical condition of many of these patients, to “start low and go

slow”. In many cases, some degree of supervision will be required.

Related Topics