Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Anxiety Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition with Panic Attacks or with Generalized Anxiety

Anxiety Disorder Due to a General

Medical Condition with Panic Attacks or with Generalized Anxiety

Definition

Pathologic anxiety secondary to a general medical

condition may occur in the form of well-circumscribed and transient panic

at-tacks or in a generalized, more chronic form. As the differential diagnoses

for these two forms of anxiety are quite different, it is critical clearly to

distinguish between them.

Panic attacks have an acute or paroxysmal onset,

and are characterized by typically intense anxiety or fear which is

ac-companied by various “autonomic” signs and symptoms, such as tremor,

diaphoresis and palpitations. Symptoms rapidly cre-scendo over seconds or

minutes and in most cases the attack will clear within anywhere from minutes up

to a half-hour. Although attacks tend to be similar one to another in the same

patient, there is substantial interpatient variability in the symptoms seen.

Generalized anxiety tends to be of subacute or gradual on-set, and may last for long periods of time, anywhere from days to months, depending on the underlying cause. Here, some patients, rather than complaining of feeling anxious per se, may complain of being worried, tense or ill at ease. Autonomic symptoms tend not to be as severe or prominent as those seen in panic attacks: shakiness, palpitations (or tachycardia) and diaphoresis are per-haps most common.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

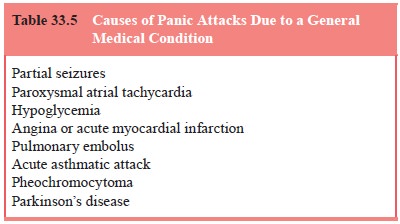

Panic attacks are most commonly seen in one of the

primary anxiety disorders, namely, panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific

phobia, social phobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder or post traumatic stress

disorder, all of which are covered elsewhere in this book. The causes of

secondary panic attacks are listed in Table 33.5. Substance-induced anxiety

disorder related to drugs of abuse (e.g., cannibis, LSD) is covered in the

relevant substance-related disorders. Partial sei-zures and paroxysmal atrial

tachycardia are both characterized by their exquisitely paroxysmal onset, over

a second or two; in addition, paroxysmal atrial tachycardia is distinguished by

the prominence of the tachycardia and by an ability, in many cases, to

terminate the attack with a Valsalva maneuver. Hypoglycemia is often suspected

as a cause of anxiety, but before the diagnosis is accepted, one must

demonstrate the presence of “Whipple’s triad”: hypoglycemia (blood glucose #45

mg/dL), typical symp-toms, and the relief of those symptoms with glucose. Angina

or acute myocardial infarction can present with a panic attack, with the

diagnosis being suggested by the clinical setting, for example, multiple

cardiac risk factors. A pulmonary embolus, at the moment of its lodgment in a

pulmonary artery, may also present with a panic attack, and again here the

correct diagnosis is suggested by the clinical setting, for example,

situations, such as prolonged immobilization, which favor deep venous

throm-bosis. Acute asthmatic attacks are suggested by wheezing, and

pheochromocytoma by associated hypertension. Parkinson’s dis-ease patients

treated with levodopa may experience panic attacks during “off” periods.

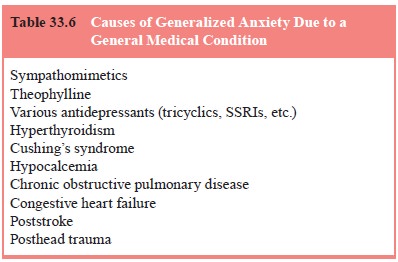

Generalized anxiety is most commonly seen in the

pri-mary psychiatric disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and is discussed

elsewhere in this book. The secondary causes of gen-eralized anxiety are listed

in Table 33.6. Sympathomimetics and theophylline, as used in asthma and COPD,

are frequent causes, as are many of the antidepressants. Hyperthyroidism is suggested

by heat intolerance and proptosis, and Cushing’s syndrome by the typical

Cushingoid habitus (i.e., moon facies, hirsutism, acne, “buffalo hump” and

abdominal striae). Hypocalcemia may be suggested by a history of seizures or

tetany. Both chronic ob-structive pulmonary disease and congestive heart

failure are sug-gested by marked dyspnea. Stroke and severe head trauma may be

followed by chronic anxiety, but this is seen in only a minority of these

patients.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Should one be fortunate enough to observe a patient during the panic attack, it is critical, in addition to carefully noting the spe-cific symptoms of the attack, to obtain vital signs, auscultate the heart and lungs, perform an EKG, and obtain blood for glucose and toxicology.

In

evaluating a patient who complains of chronic anxi-ety, it is important, before

deciding that this is, indeed, a case of pathologic generalized anxiety, first

to determine whether or not the patient has a depression, whether it be primary

or secondary: depression is often accompanied by anxiety, and such anxiety

clears upon adequate treatment of the depression. Assuming that the patient,

however, is not depressed, a work-up should include the following: auscultation

of the heart and lungs; CBC and liver enzymes (looking for the telltale

“alcoholic” combination of an elevated mean corpuscular volume and elevated

transaminases); thyroid profile; cortisol level and calcium level.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

Although epidemiologic studies are lacking, the

clinical impres-sion is that anxiety secondary to a general medical condition

is common.

Course

This is determined by the underlying cause.

Treatment

Treatment is directed at the underlying cause, and

this is suf-ficient for all cases of secondary panic attacks and most cases of

secondary generalized anxiety: exceptions include poststroke and posthead

trauma anxiety, and in these cases benzodiazepines have been used with success.

Related Topics